Aftermath

Art in the Wake of WWI at Tate Britain

In our current state of affairs, death and disaster is a near constant presence in our media saturated culture. So it may seem that World War I, which ended exactly a century ago, was simply a historic event that now gathers dust in history books. However, this was the first case of truly modern warfare (and its many terrors), and the political aftermath in Europe was a major factor in the rise of fascism only a decade later.

A new exhibition called Aftermath: Art in the Wake of World War One at Tate Britain in London explores the responses that artists across Europe had to the unimaginable horrors of their era. Focusing mainly on English, German, and French art from the teens and twenties, this is an exhibition that shows nuanced reactions to this collective trauma. Ranging from the utopian to the bleak to the absurd, this was a time of reckoning on a mass scale.

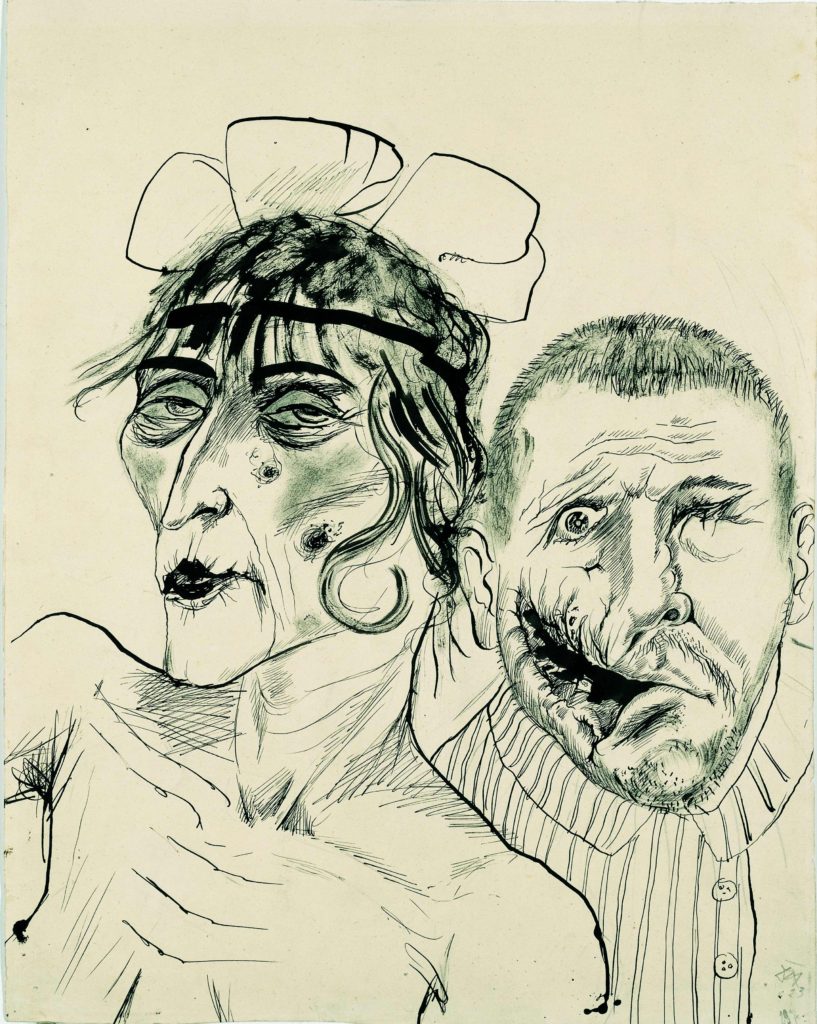

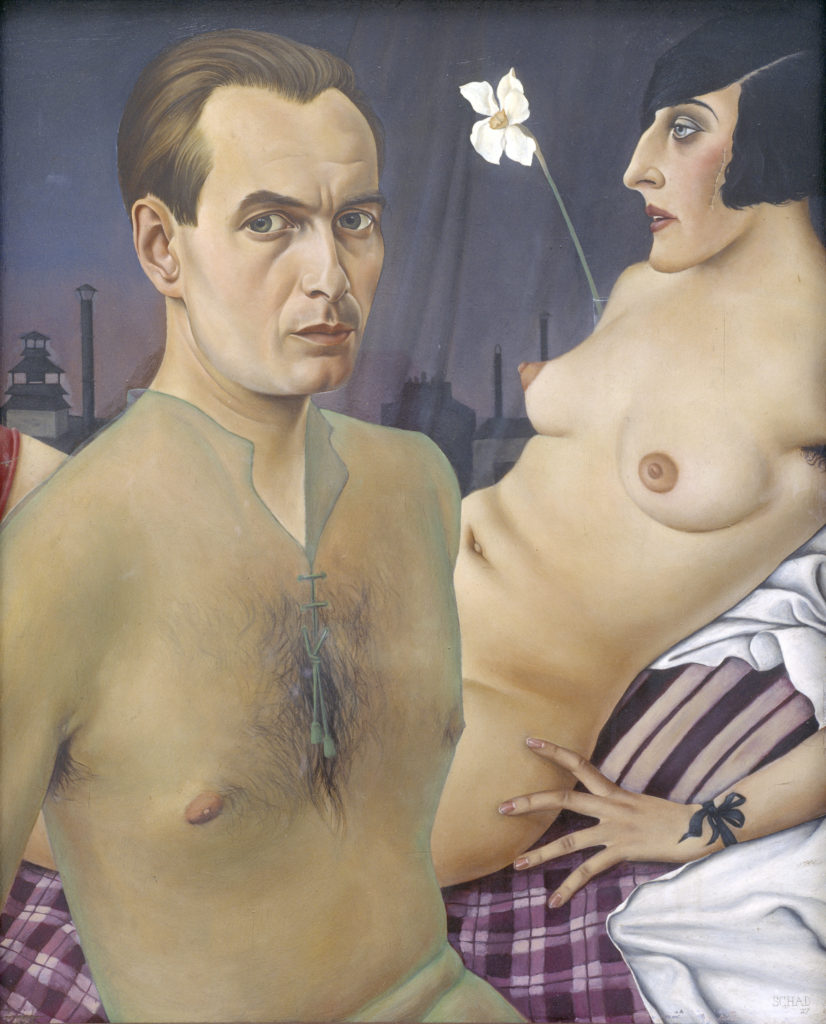

The most disturbing works are surely represented by German artists. George Grosz, Otto Dix, and Christian Schad utilized their Expressionist roots to represent the bleakness of modern living. Dix and Grosz were particularly focused on veterans and marginal figures in society who often suffered most following the war, especially in the ruined economy of Germany. Empty skulls, maimed soldiers, and tired prostitutes are prominently featured, and shown suffering like medieval martyrs. Schad, although in similar circles as someone like Dix, was slightly different in that his paintings were almost neoclassical in their smooth rendering and simple compositions. The twist here is the modern individuals shown in his paintings. Some women might be nude or in sheer clothing. Usually they have bobbed hair and attitudes that range from indifferent to imperious. Dirty gray cities might be contrasted by a flower or a champagne bottle. There is a realism to his work, yet all of Schad’s paintings seem like dreamscapes. This in its own way, represents perfectly the conflicts within Germany in the 1920s.

Western Europe was a different story entirely. After the birth of Cubism and other radical departures from traditional art making, figurative artwork made somewhat of a comeback. Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, the inventors of Cubism, were painting works that were much more conservative compared to their earlier innovations. Unlike their German counterparts, Meredith Frampton, Fernand Léger, and Winifred Knights (who are all represented in this exhibition) envisioned something more palatable. Whether embracing the future, or looking nostalgically to the past, artists in France and England offered up an escape from the energy and destruction of the previous decade.

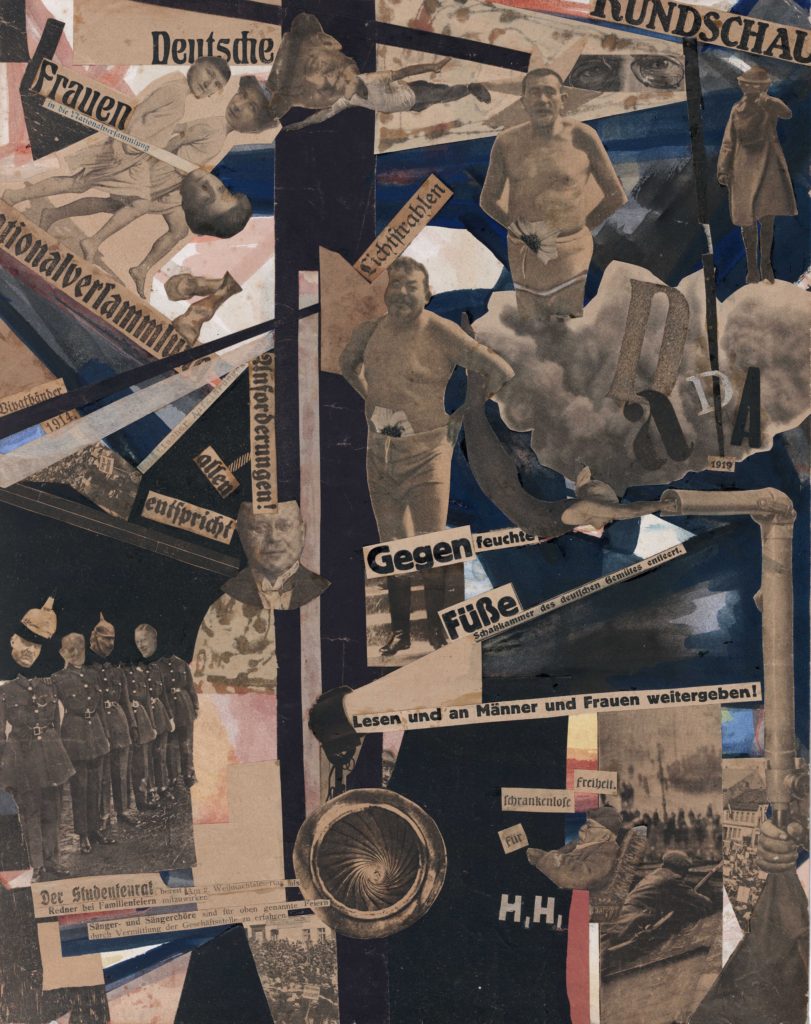

After World War One, schools of thought emerged that the modern world was entirely absurd and that art should represent this: Dada was the result. As a form of art most known for its Swiss and German roots, its spread across Europe was rapid. This might be in part because of its Communist ideals, and that Dada encompassed all art forms, not just painting or sculpture. Later, Dada evolved into Surrealism and heavily influenced Pop in the 1960s. By using collage, abstraction, found objects, and mass media as their materials, artists like Hannah Höch, Marcel Duchamp, and John Heartfield satirized politics and upended high culture in equal measure. As normal as that might seem now, it was radical, even dangerous then. Rather than escape or wallow after a generation of men are killed, why not represent the preposterousness of the world?

Aftermath is a brilliant exhibition, filled with greater and lesser known artists, and the Tate also acknowledges the intellectual and stylistic overlaps amongst these artists. However, this is a show that is an ode to art and the artist. After great turmoil and sadness, artists were able to emerge and produce some of the most innovative work of the twentieth-century. This isn’t to say that an Otto Dix drawing or a Dada collage made World War One worth it. In fact, I doubt anyone sane would choose art over millions of human lives, but when faced with this brutality, art functioned as catharsis, optimism, and resilience.