Allure and Anger

David Wojnarowicz at the Whitney, NYC

David Wojnarowicz began as one of many artists and poets in 1980s New York, but now he lives on as a legendary figure that represents art engaged with activism, politics, and marginalized communities and histories. The Whitney Museum’s spectacular (and long-awaited) survey of the artist’s work, called David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night, shows how he refused categorization in his art and writing practices, and fought tooth and nail for the communities that were suffering from AIDS, government neglect, and many other forms of violence.

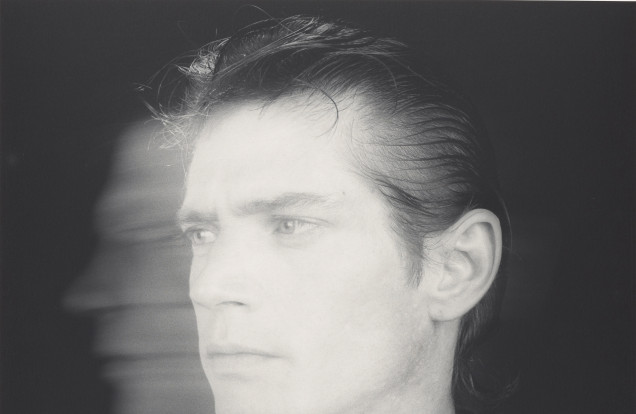

After a difficult childhood and then living a transient life in the 1970s, Wojnarowicz came to New York in 1978. He viewed himself originally as a writer, and was writing poetry and performing in new wave bands. However, he began making serious attempts at art with his series Rimbaud in New York in 1978 and 1979. Rimbaud consisted of photographs of a man doing all sorts of activities, from masturbating to riding the subway to shooting up, all while wearing a Rimbaud mask. Wojnarowicz viewed Rimbaud, along with Jean Genet, as geniuses. Their embrace of their troubled beginnings, marginalization, and queerness was a model that resonated with the artist.

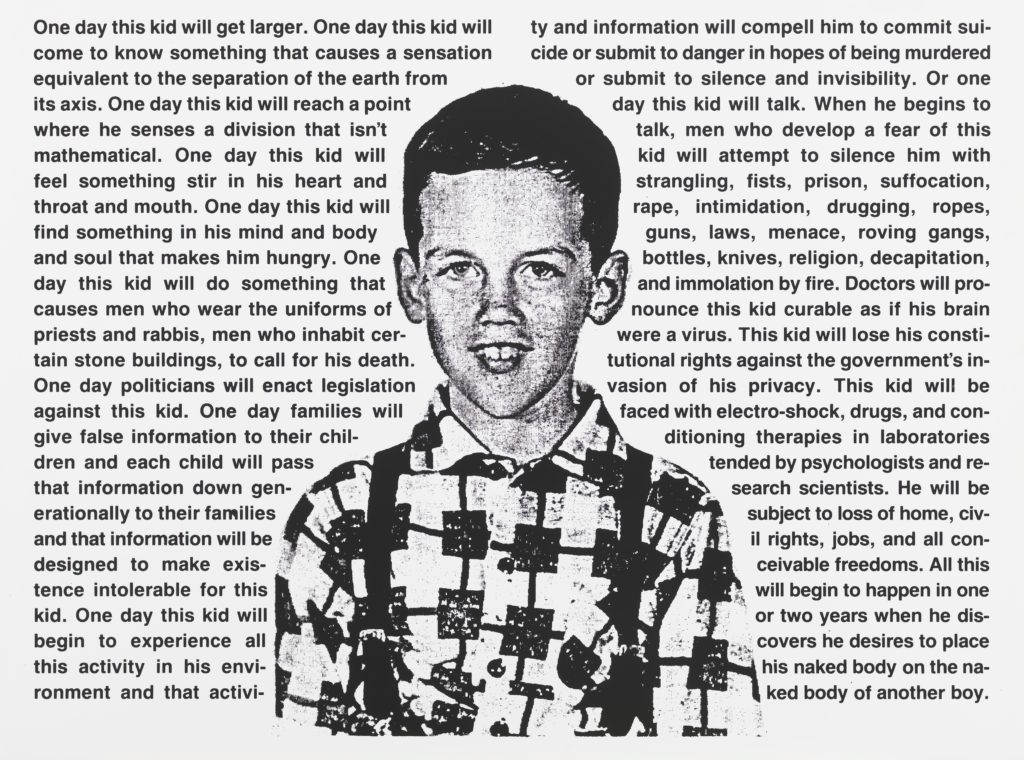

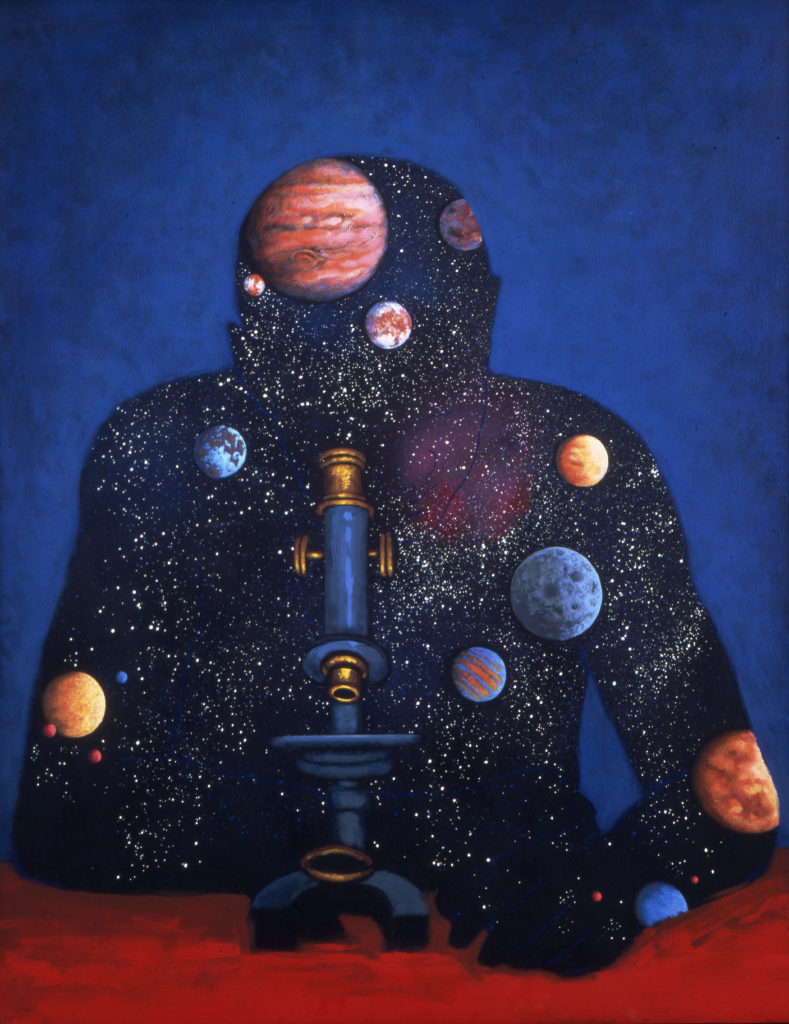

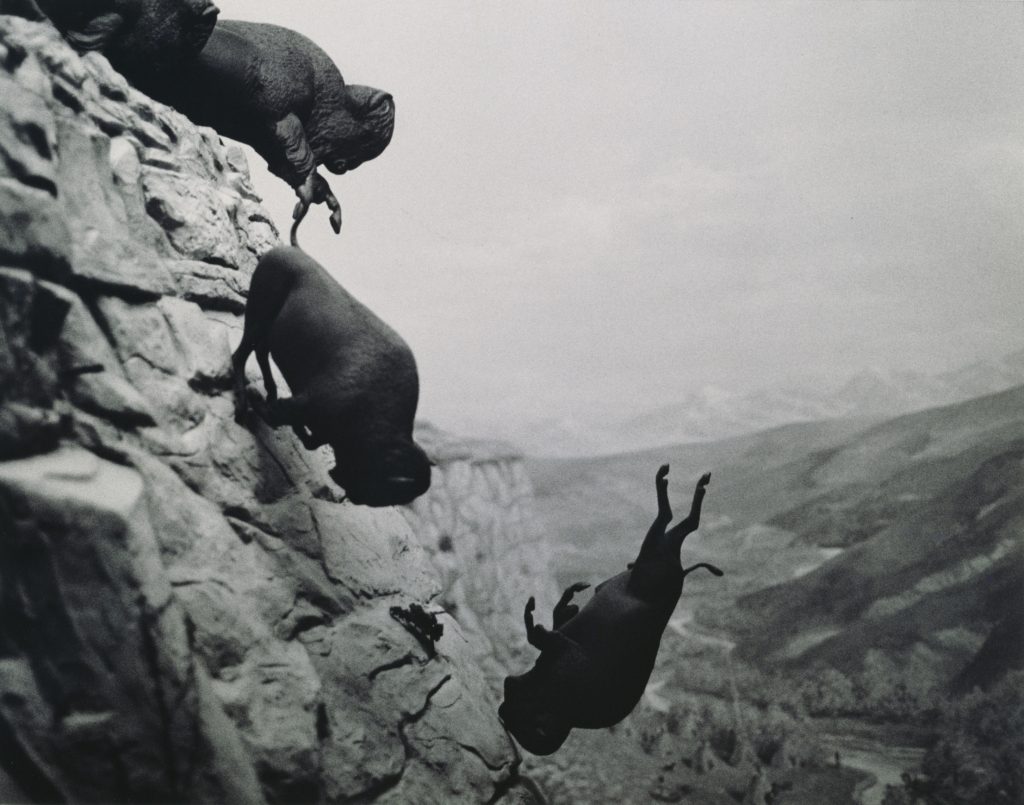

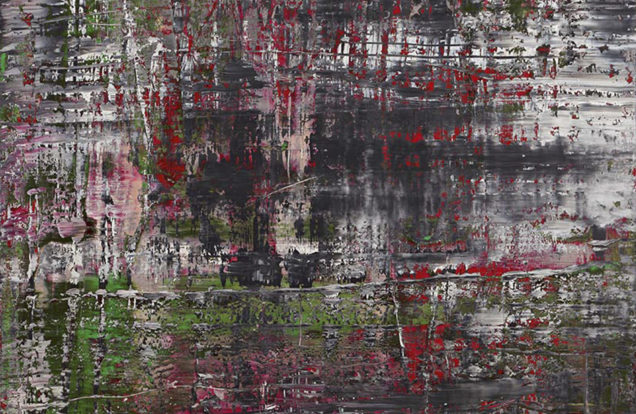

By 1980, Wojnarowicz met the photographer Peter Hujar. This was a turning point for the artist because his lover turned friend and collaborator convinced him to focus on painting. After spending the early ‘80s doing everything from sculpture to collage to graffiti, Wojnarowicz was making symbol-laden paintings that became epic in narrative and scale. History was always a major theme for these works, and for Wojnarowicz, history was defined by toxic masculinity, colonization, corruption, and destruction. The AIDS crisis also began to play a prominent role in Wojnarowicz art and writing. His community was being devastated, and they were all but ignored by the Reagan administration. Hujar, who was a critical mentor and friend to the artist, finally succumbed to AIDS in 1987. In that same year, Wojnarowicz learned he was HIV-positive.

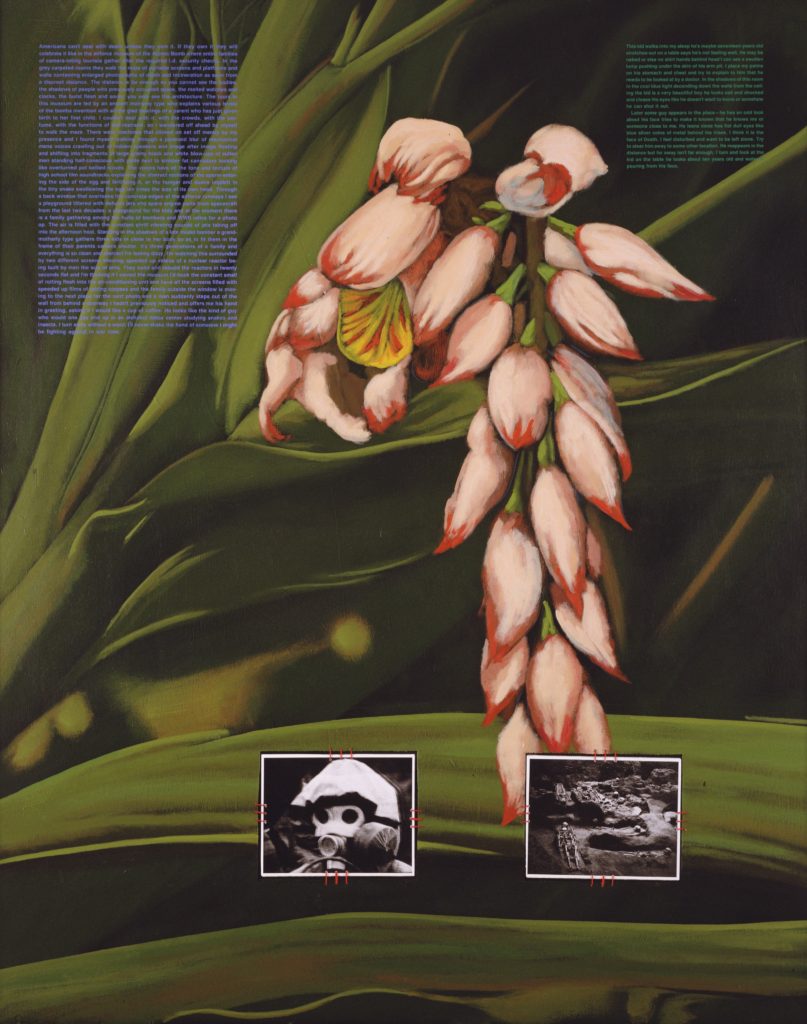

1987 can be seen as another shift in direction for this artist. Wojnarowicz was always interested in the disenfranchised and critiques of power, but AIDS activism quickly became his primary focus. Using photographs of Hujar on his deathbed, clocks and street signs, acts of gay sex, and his own writing, Wojnarowicz condemned the conservative politics that were causing thousands to die while bringing attention to his community’s plight. His later work relied more heavily on photography, collage, and text. Ironically, the fiery canvases of the mid-1980s don’t even have the power of these seemingly more subdued works. If anything, by working in a more pared back style, the artist leaves the viewer with a purer sense of rage, grief, and beauty.

In 1992, Wojnarowicz died from AIDS. He left films, texts, and artwork unfinished, and it is impossible not to wonder how much more this artist had in him if he had lived on. He is one of many who was cut short, yet it is remarkable that a man created such an accomplished body of work in just fourteen years. Today he still influences artists who float between medium and technique, and his tenacious activism is an example that shines well beyond the art world. In this era of tumultuous and regressive politics, the Whitney’s exhibition is certainly somber and even heartbreaking. However, just like the work of Wojnarowicz, empowerment overshadows the sadness.