A Queer Modernism

"Lincoln Kirstein's Modern" at MoMA

American Modernism at a glance always seems to be imbued with the sense of heterosexual masculinity. Think of the hearty regionalism of Thomas Hart Benton, the chaotic city scenes of a George Bellowes painting, or the angsty aggression of any Abstraction Expressionist. However, queer artists had a defining impact on the development of the United State’s arts and culture. In Lincoln Kirstein’s Modernism, an exhibition on view now at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, history is revised. Not only were they part of American Modernism, but many LGBT+ individuals founded, subverted, or influenced some of the most important art institutions in this country.

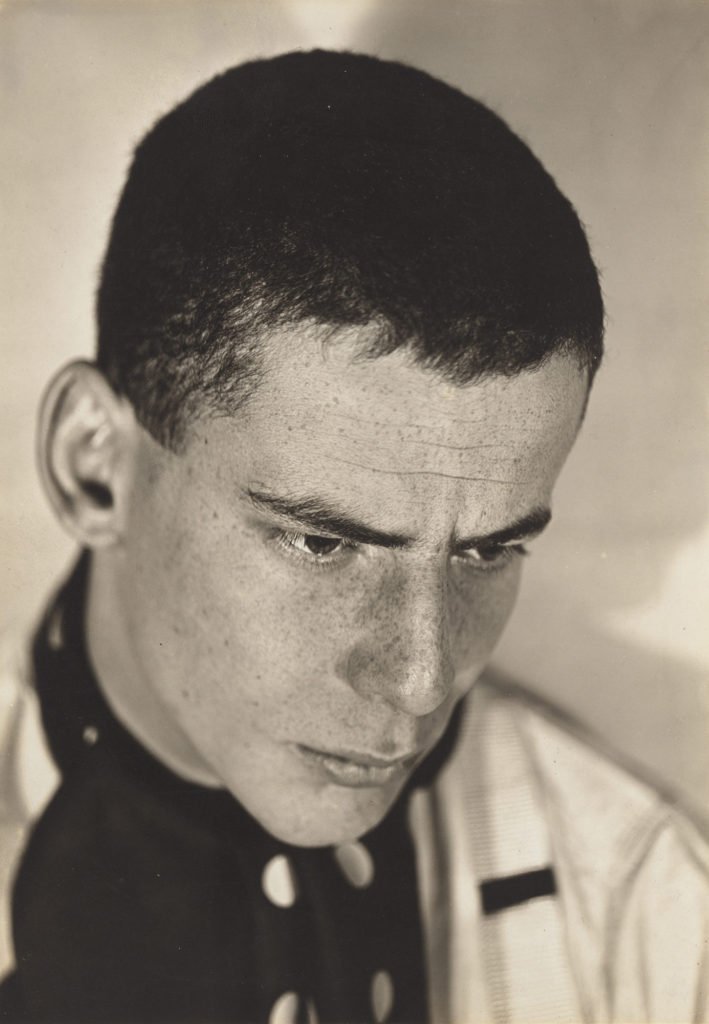

Growing up in a wealthy family, Kirstein had access to some of the best education (and connections) available. In 1927, he created a literary magazine called Hound & Horn while still at Harvard. It was admired by artistic circles in New York, but Kirstein ceased publication in 1934 to focus on the project that would elevate his name to true prominence. In 1933, Kirstein had a chance to see Apollo, a ballet by George Balanchine. Soon after, Kirstein would partner with Balanchine to found the School of American Ballet which moved permanently to New York the following year. Just a few months later, the company was renamed the American Ballet (it would become the Met’s resident company.) After the frenzy of World War II, Balanchine and Kirstein started over and created the Ballet Society, and was later known as the now iconic New York City Ballet. The ballet was the greatest passions in their lives, and Kirstein and Balanchine would remain with the company well into the 1980s.

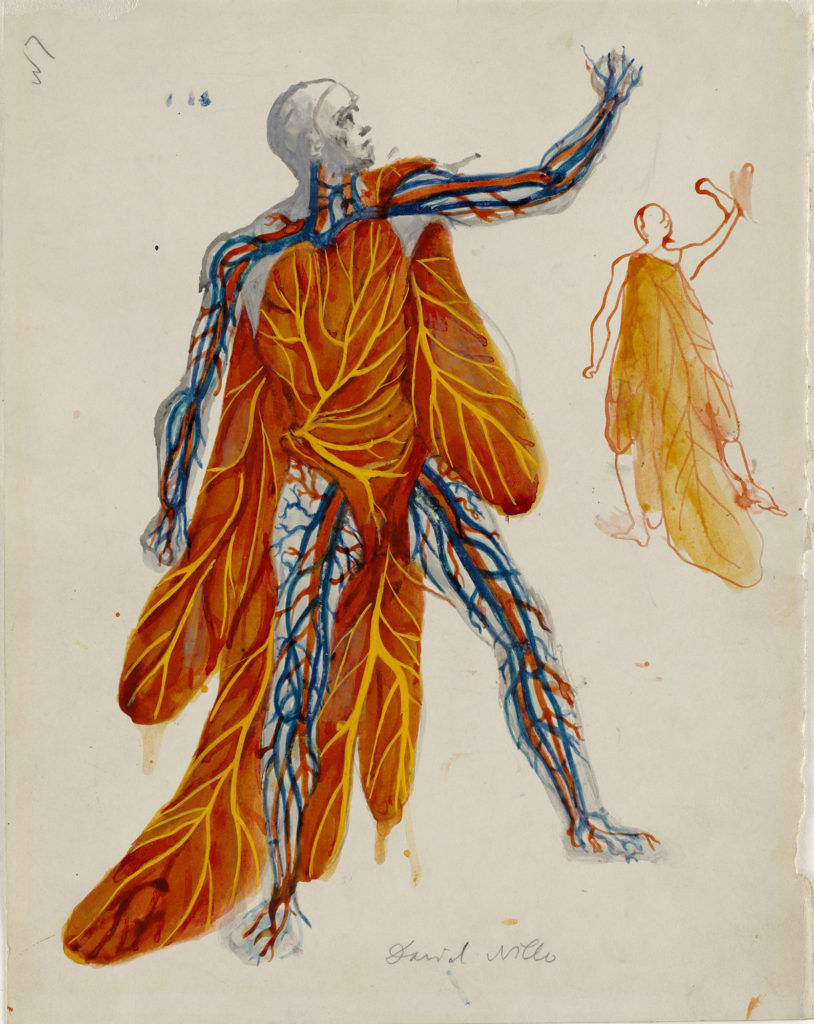

Kirstein himself did not exactly produce art or dance, but he had an exceptional eye. He recognized it in Balanchine and many others, who later became friends and collaborators. Many of these individuals were queer, too. Paul Cadmus and Jared French, notable artists and lovers, would design sets and costumes for ballets. Walker Evans and George Platt Lynes would photograph dancers of various productions. Philip Johnson’s architecture firm even designed lavish Lincoln Center in the 1960s. All of the collaborations produced work that inevitably contained sublimated (or not so subtle) scenes of queer desire. High art was essentially infused with an erotic frisson. In an effort to preserve the important work of his colleagues, Kirstein even once created a dance archive and department for the Museum of Modern Art to preserve and elevate these projects.

What this exhibition primarily does is link together the various nodes of queer artists, designers, and performers who came to shape the New York’s artistic culture, with Lincoln Kirstein as the main intersection. Although this show shines a spotlight primarily on white, cisgendered gay and bisexual men, this exhibition feels like another needed course correction that MoMA has been pursuing lately with their more recent exhibitions and new renovations. Whether you go for the ballet or the queer artifacts, it is a worthwhile journey to midtown Manhattan.