APPROPRIATION IN ART

The Fine Line Between Stunning Art + Theft

When Marcel Duchamp submitted his “readymade” Fountain to the Society of Independent Artists for exhibition under the pseudonym “R. Mutt,” it was clear what can be considered art, as well as what is and isn’t original work, was evolving and it would never be the same again. The piece in question consisted of a white porcelain urinal that was signed “R. Mutt, 1917”. At first, the Society’s board of directors rejected the submission, as it assumed it to be related to bodily waste and, therefore, an indecent display, as well as not an original work. They censored it even though the Society was supposed to accept all submissions. The exhibition, in which Duchamp served as head of the hanging committee, was meant to be free of juries, prizes, and subjectivity. But, regarding Fountain, the board issued a statement defending that it may be beneficial, but its place was not an art exhibition as it was not art.

Regardless of whether Fountain was art or not, the question of who should get the credit for its creation remains. By signing it and giving it a new name, Duchamp changed the urinal’s meaning and function (re-contextualized it in a way), but he had no part in the object’s actual production. So, can he take credit for Fountain? Is it re-contextualization, or straight-up plagiarism? The New York DADA magazine “The Blind Man” defended that it didn’t matter whether the artist had had a hand in the object’s actual production, as he had chosen it and given it a new meaning.

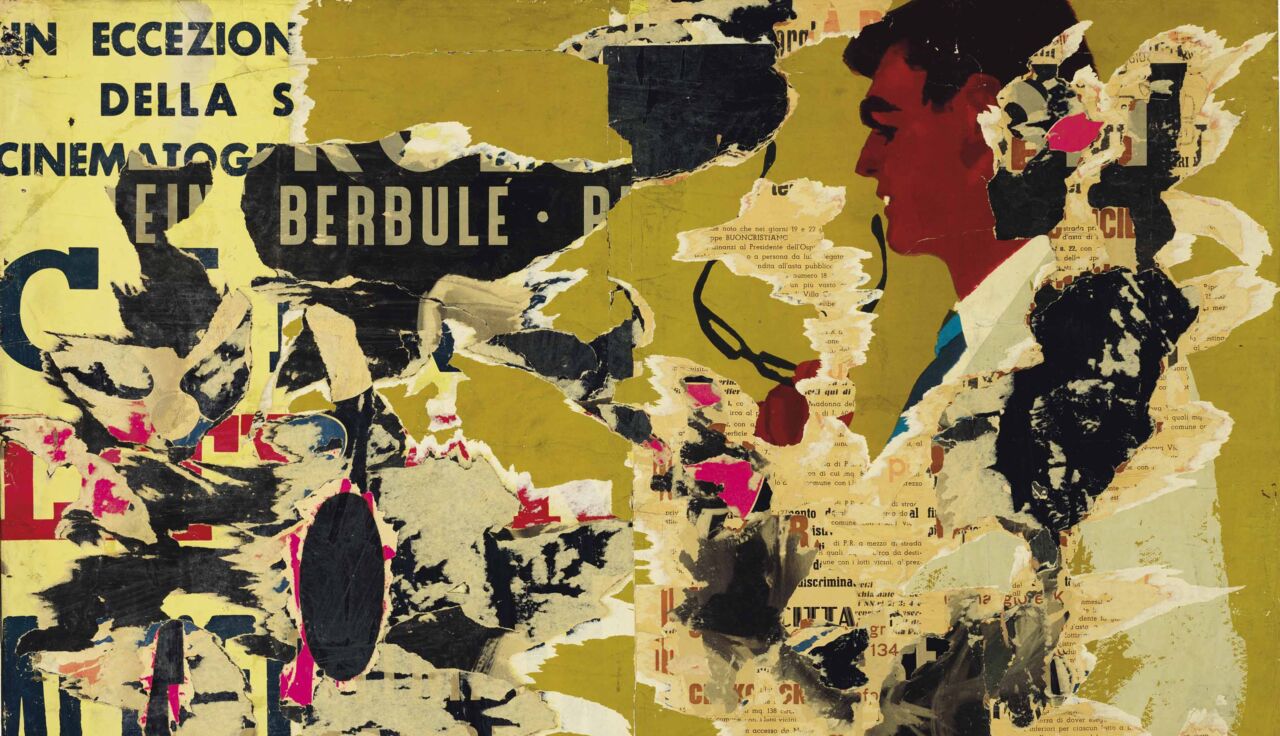

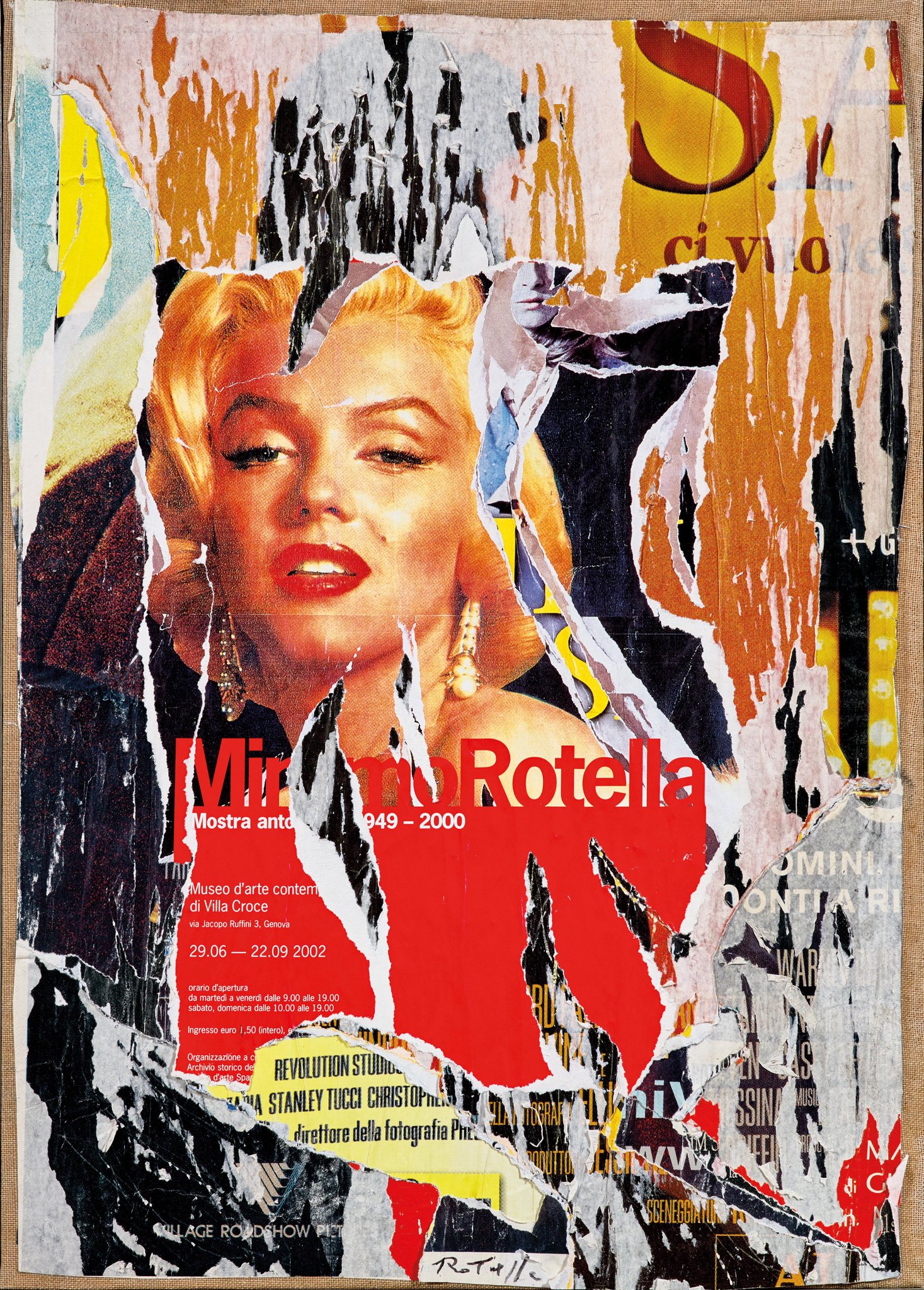

Appropriation in art is a concept that seems to have appeared at the beginning of the twentieth century, as artists began to use pre-existing images and objects in their works. It can be traced back to Cubism and Dadaism and is exceptionally present in Surrealism and Pop Art. Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque began incorporating everyday objects into their collages, and Dada artists such as Duchamp continued to test the possibilities of what could be art. Later on, Surrealists such as Salvador Dalí also pushed these boundaries by creating works such as Lobster Telephone (1936). Pop Art artists such as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, or Mimmo Rotella appropriated images from popular culture (including logos, celebrities, pictures from comic books or posters) in their work, exploring the influence and effects of mass-produced objects and images.

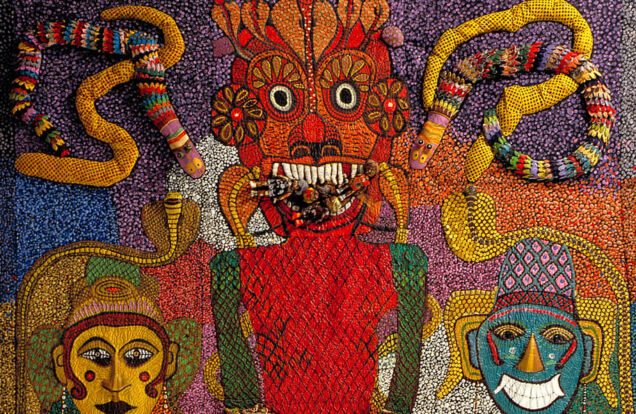

A controversial example of appropriation is Picasso’s “stealing” of African art (or what has been called “Primitive” art). Tribal masks inspired his famous painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and are one of the most popular art history discussions, as the five figures depicted. This is where a big problem arises, and it’s the fact that Picasso was “inspired” by this art that he stole for the work he was creating in the western world. It is a case of Cultural Appropriation. And it is wrong to take something that already exists and make it your own with complete disregard for its provenance or original value and significance. To this day, African artists state that their work is compared to Picasso’s or other Cubist artists when, in fact, it was Picasso who borrowed from their techniques.

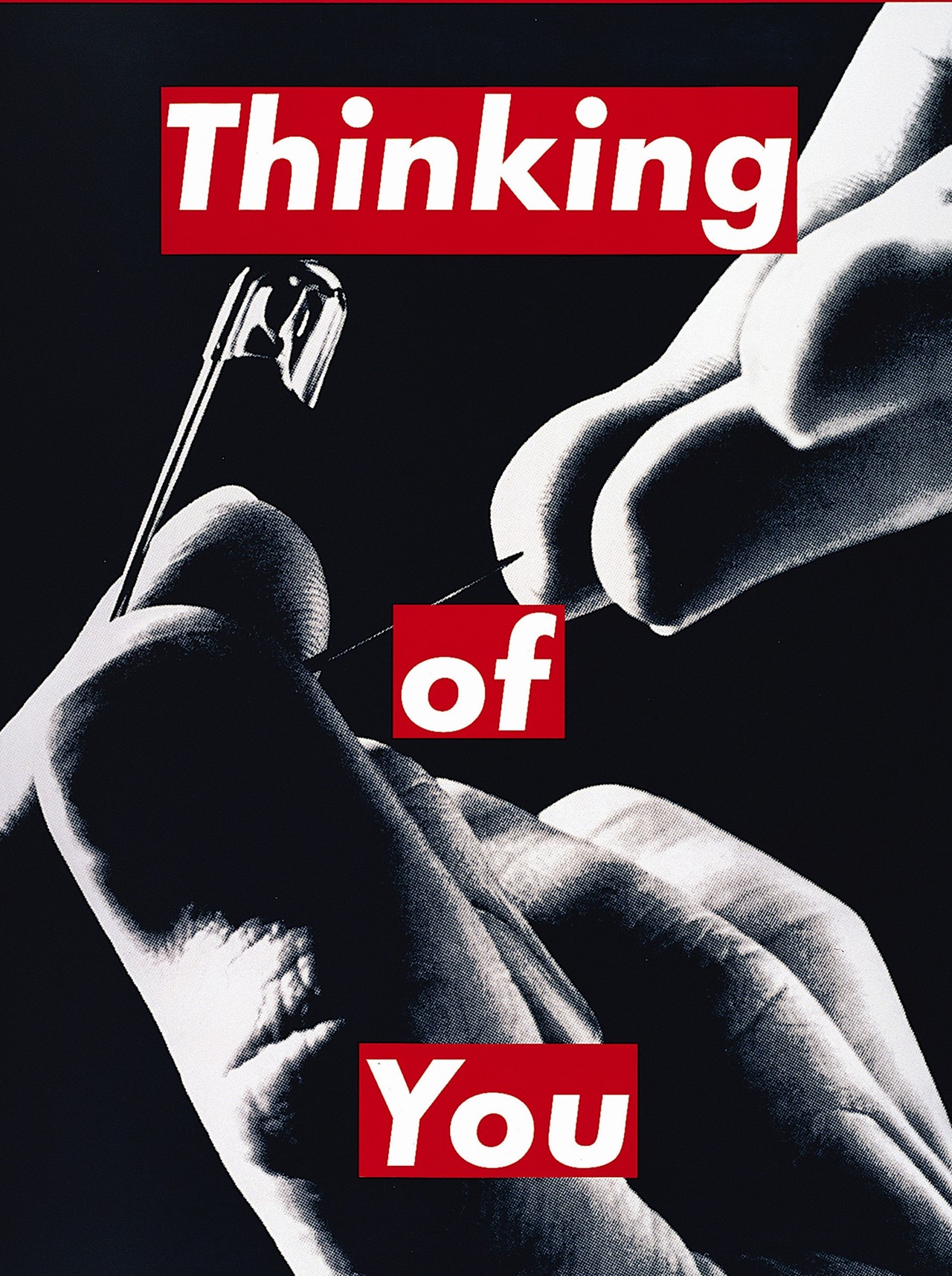

When speaking of appropriation art in the second half of the twentieth century (it has been used extensively since the 1970s and ’80s), some of the names that come to mind are Sherrie Lavine, Richard Prince, and Barbara Kruger. Sherrie Levine is an artist primarily known for producing exact replicas of famous artworks and photographs from Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Edward Weston, or Marcel Duchamp. In 1991 she made her version of Duchamp’s Fountain, but with a polished bronze finish. Levine has become an important figure in feminist art, as many of the works she remakes are by male artists who completely dominated the art world. By appropriating these works, she re-feminizes them. Another feminist postmodern artist is Barbara Kruger, whose work mostly consists of found photographs paired with assertive and sometimes aggressive text. Like Levine, her work is feminist, as well as critical of society and capitalism.

Ironically, the clothing brand Supreme (its logo was appropriated from Kruger’s work) filed a lawsuit against another brand for using its logo on t-shirts. While imagery appropriation can be justified many times as a means to an end in the art world, consumerist society does not always work in the same way. Kruger, who has never taken legal action against Supreme for its logo, responded to the incident saying: “What a ridiculous clusterfuck of totally uncool jokers. I make my work about this kind of sadly foolish farce. I’m waiting for all of them to sue me for copyright infringement.” This is not to say that copyright infringement lawsuits are not extremely common among artists. For example, Jeff Koons is an artist who has been sued on multiple occasions, and so has Richard Prince. Fair use was incorporated into US law with the Copyright Act of 1976 and is a defense when an artist can justify their use of a work. The court will analyze different factors to determine if fair use applies in a case of copyright infringement, including whether the appropriation was for commercial use or commentary, the elements that the appropriated work contains, or the effect on market value.

Appropriation is problematic when it equals oppression, as in the case of Picasso’s borrowing of African art, but can it be justified if it is serving as a means to move forward? Duchamp’s Fountain pushed the boundaries of what can be made into art. On the other hand, Levine’s Fountain took Duchamp’s and turned it into a commentary of patriarchal dominance in art history. Is it even possible to create an essay about today’s society without appropriating images and risking the possibility of getting sued? One thing is sure, and it’s that this conversation is far from over.