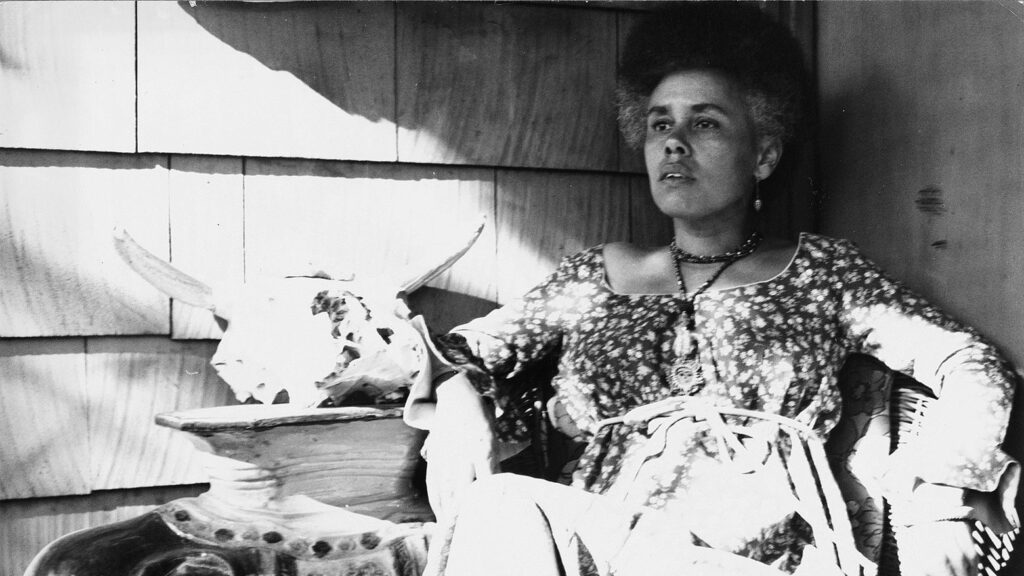

Betye Saar

The 93-Year-Old Artist Still Making an Impact

2020 is one of global distress, but artist Betye Saar is having a fantastic year—and at the epic age of 93, she certainly deserves it. Her exhibition Betye Saar: Call and Response—the first comprehensive show of her work and first public display of her sketchbooks by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) opened in September 2019. The short/documentary about her practice “Betye Saar: Taking Care Of Business” (2020) was well-received at this year’s Sundance and was set for the canceled SXSW film festival. With a remarkable career spanning over six decades, Betye Saar has more than earned this critical acclaim and attention.

Iconic, legendary and ground-breaking are all adjectives frequently used to describe Saar in the contemporary art world. Growing up in Los Angeles and Pasadena, California, Saar often collected miscellaneous ephemera to create objects—a habit that she would later develop into her hallmark after studying at the University of California, Los Angeles. Saar was influenced by the found object sculptor Joseph Cornell and the Italian-American artist Simon Rodia. In the ’60s, she began creating politically-charged assemblages that critiqued racism in the United States. Much of her work deals with intersections of black power, spirituality, mysticism and feminism evident in works like Black Girl’s Window (1969), where a salvaged wooden frame encloses a dark figure pressed against a transparent surface as astrological symbols hover in vignettes above. When discussing the piece, Saar told MoMA, “Even at the time, I knew it was autobiographical… We’d had the Watts Riots and the black revolution. Also that was the year of my divorce. So in addition to the occult subject matter there was political and also personal content.”

Her best-known piece is The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972). It is where a stereotypical African-American “Mammy” figure holds both a broom and a rifle with a clenched fist echoing the black power symbol. It is collaged into the assemblage’s center and credited by Black Panther activist Angela Davis as having sparked the black women’s movement. Through repurposing found objects, Saar transformed the racist domestic caricature into a militant and powerful symbol.

Another compelling piece tackled similar themes and was featured in LACMA’s exhibition–I’ll Bend But I Will Not Break (1998). The installation includes a flatiron chained to the leg of an old ironing board (found by Saar at a rummage sale) with a stark white sheet hanging on a clothesline in the background with the KKK monogram embroidered subtly into the sheet’s edge. An 18th-century British diagram of the packed hold of a slave ship in the Middle Passage and pictures of a black woman bent over her ironing adorn the ironing board was also part of the design. It blurred images of Slavery’s forced labor with that of Jim Crow’s restrictions, imbuing the artwork with in-depth historical and racial commentary.

In Robert Barrett’s “Conversation with the Artist” from Betye Saar: Secret Heart (1993), Saar explained, “To me, the trick is to seduce the viewer. If you can get the viewer to look at a work of art, then you might be able to give them some sort of message.” Today, Saar’s work and messages resonate as strongly as ever.