Deep Cuts

Lucio Fontana at the Met Breuer

Certain artists throughout history have been able to push their mediums in new and powerful ways. Over the course of western Modernism you can see periodic breakthroughs. For example, Manet introduced Impressionism, af Klint and Malevich reached total abstraction, Picasso broke down the pictorial plane, Pollock introduced the drip. However, another figure introduced an important additions as well: Lucio Fontana. The Italian and Argentinian artist is the subject of a new retrospective entitled Lucio Fontana: On the Threshold at the Met Breuer, and finally, this master gets his dues.

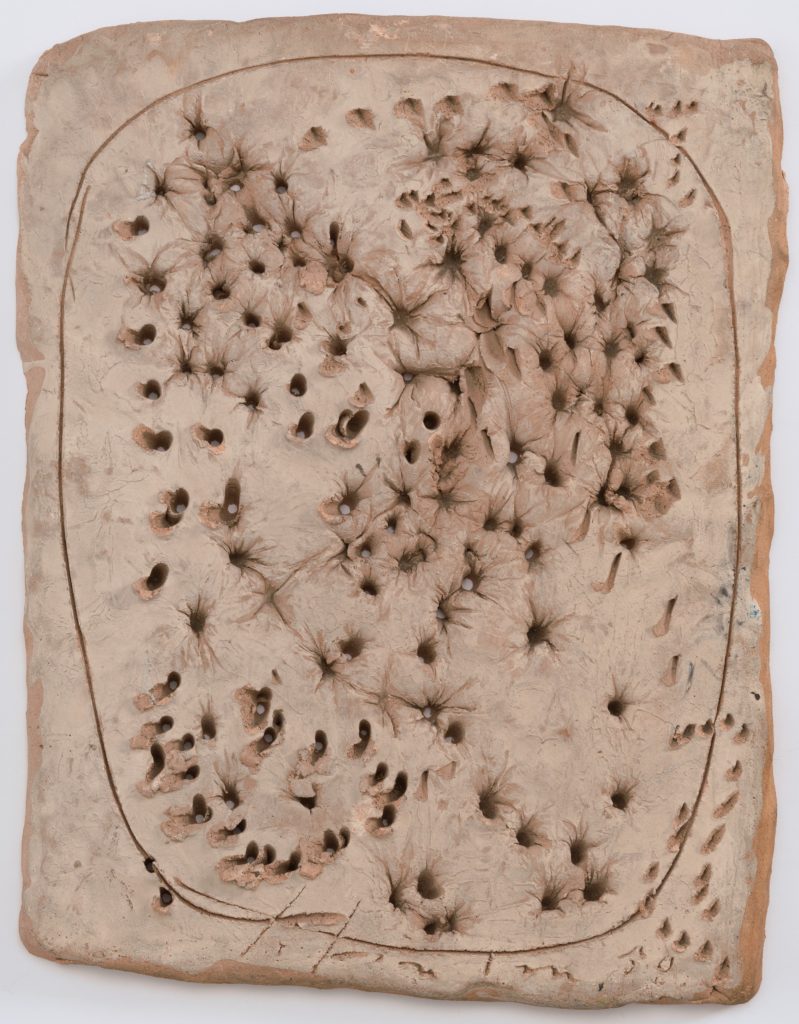

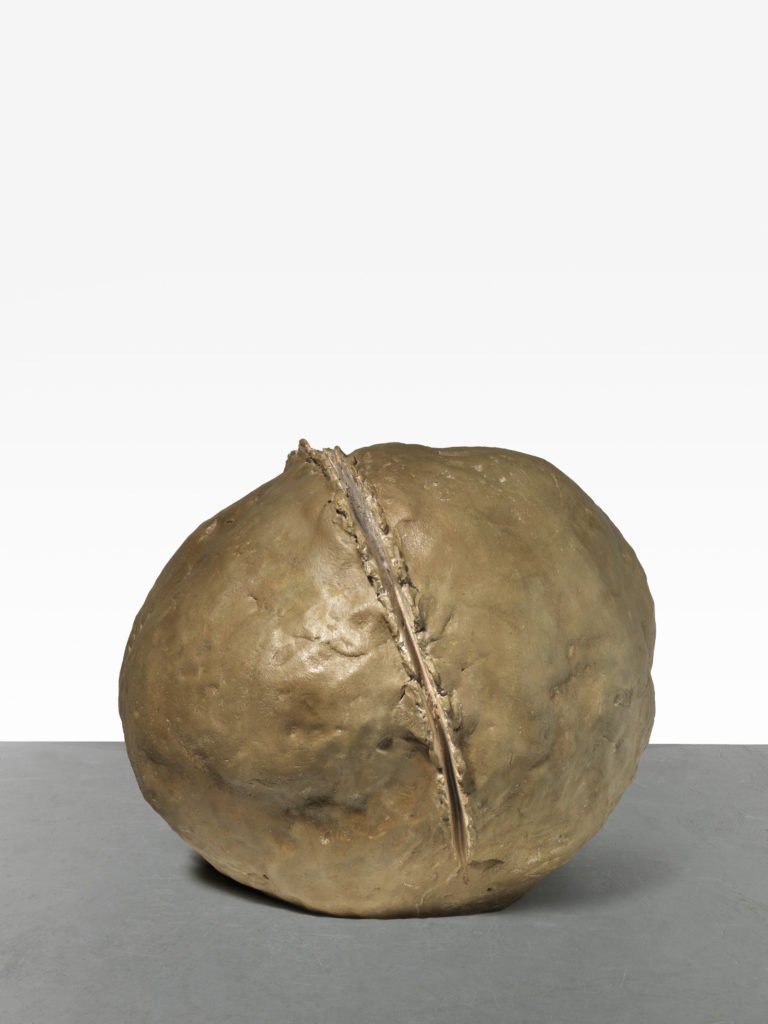

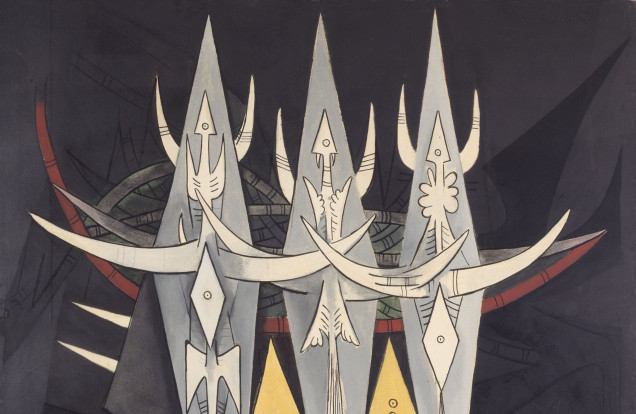

Unlike the previously mentioned artists, Fontana was much more focused less on a sculpture or painting, but the space in and around it. Early in his career, Fontana used sculpture in the form of bronze and ceramic that fluctuated between the figurative and the abstract. However, even in many of these works from the 1930s and ‘40s, Fontana’s sculptures seem to gesture outward into space, others sport holes, nooks, and crags. They also feel in step with the time, with their echoes of Giacometti and German Expressionism, but a radical creative shift would soon occur for Fontana.

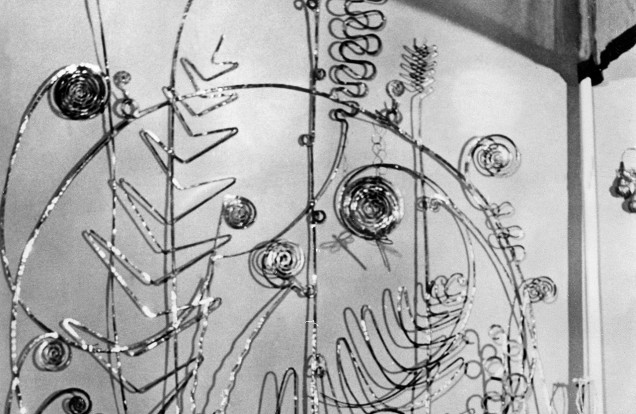

By 1947, Fontana was nearing the age of fifty, but was about to enter the most fruitful phase of his career. During that year, Fontana and a group of peers signed “The First Manifesto of Spatialism.” Spatialism was Fontana’s attempt to unite sound, color, space, movement, and time into a new form of art that rejected traditional painting and sculpture, but incorporated new technology. In 1949, his work began to appear riddled with holes (which he called “buchi.”) They are roughly hewn, and seem almost violent. The works themselves reveal the space within and behind them, thus creating what Fontana called a “fourth dimension.”

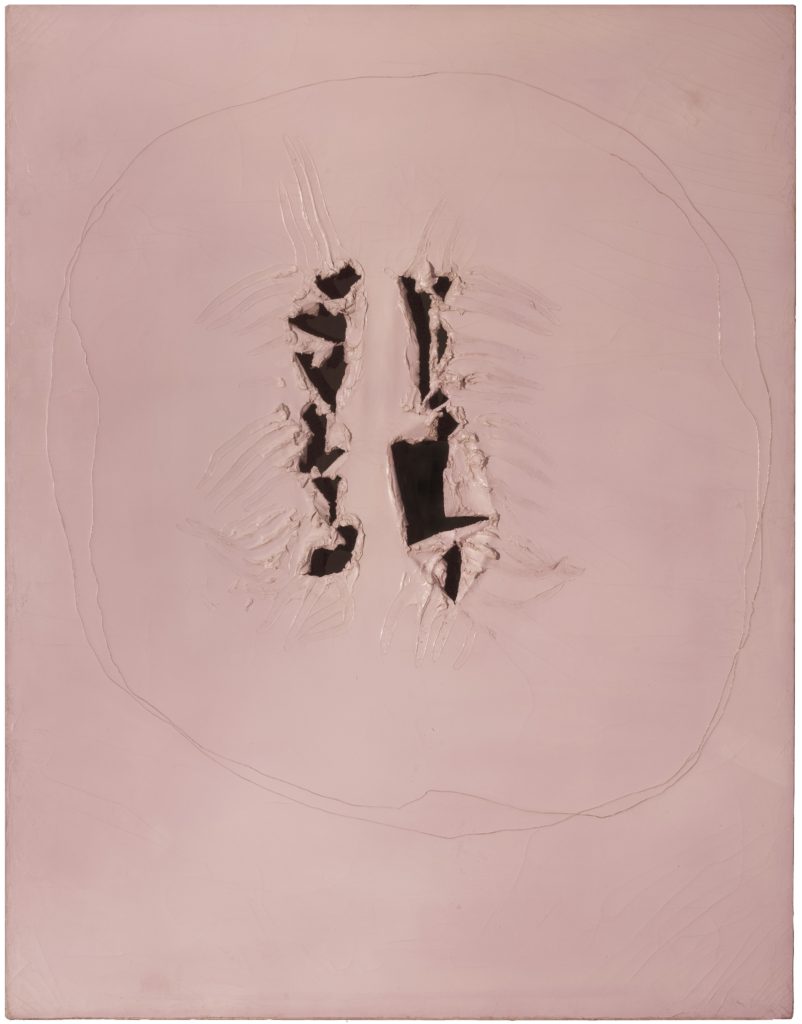

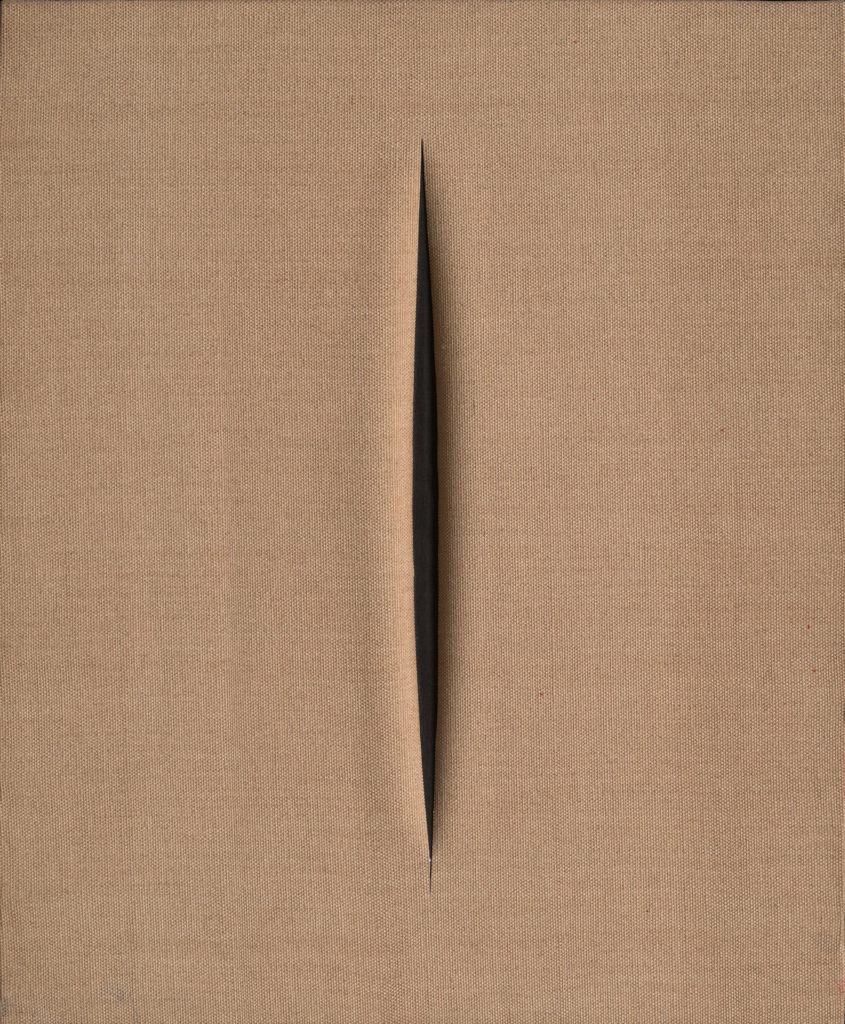

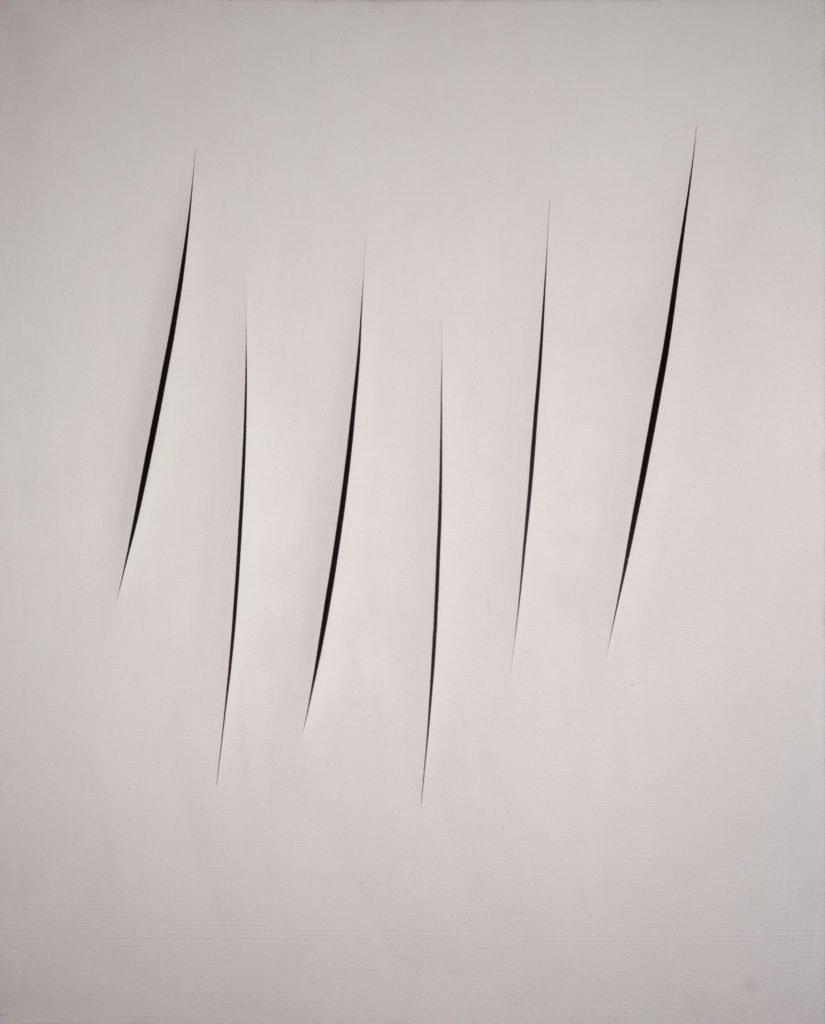

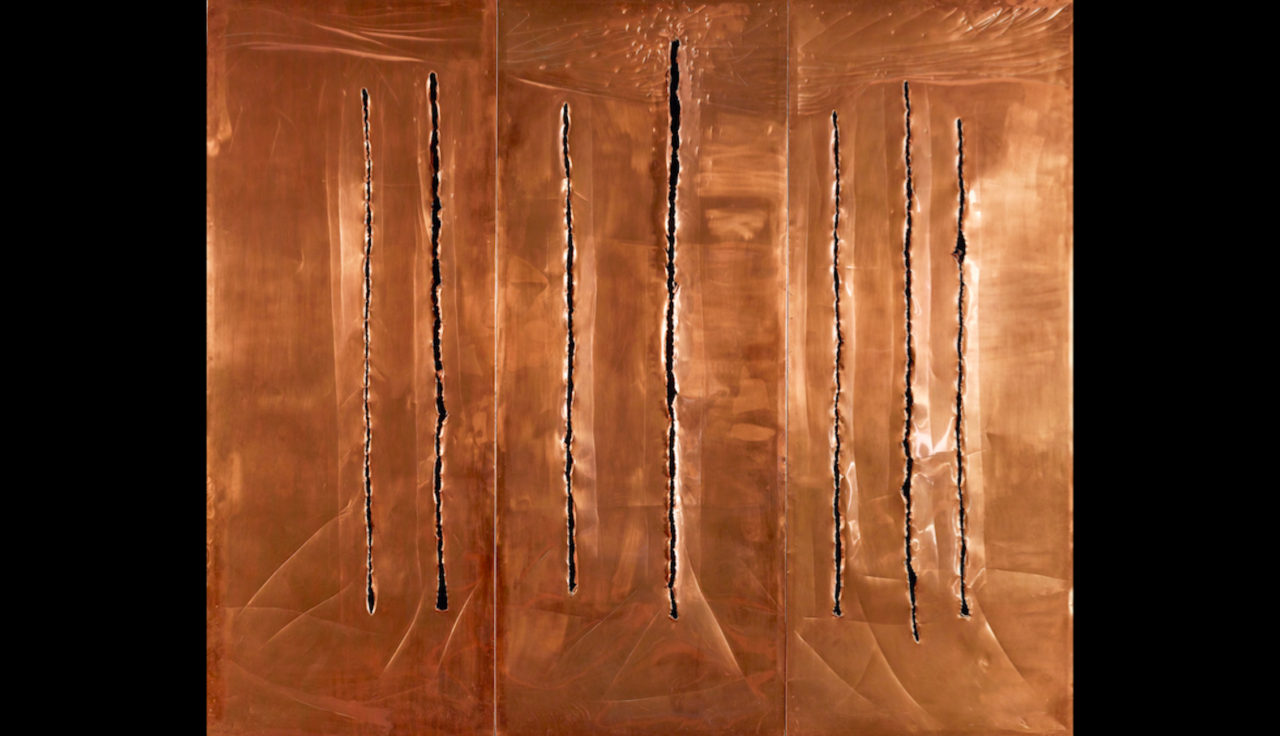

These Spatial Concepts eventually became more streamlined and focused. By the mid to late 1950s, holes were almost uniformly covering the surface of elegantly shaped canvases, and the final evolution came with the cut. The work I am describing is the artist’s most famous. They are vivid monochromes that Fontana would slice with a razor while the paint was still wet. After the paint dried, he would often add black gauze to give the appearance of an abyss of infinite space behind the canvas. These might come in the form of a single cut or many. Fontana then turned to cutting white monochromes and finally metal before turning to space itself in the last few years of his life. Although he experimented with environments in the 1950s, a decade later, he would use color, light, and architecture to bring Spatialism into an enveloping experience for the viewer. The installations at the Met are certainly a reminder of what a beautiful triumph these works were before Fontana’s death in 1968.

While the Met isn’t always known for modern and contemporary exhibitions, this is certainly a success. It explores the life and art of an exceptional artist who contributed greatly to painting, sculpture, and even future movements like installation and environmental art. Whether or not you believe in Spatialism, and the rest of the heady Modernist movements and manifestos, it is undeniable that Fontana produced incredible and stirring work as a result of his pursuit for the infinite.