East / West

"Van Gogh & Japan" in Amsterdam

The non-western world is the stylistic foundation for western Modernism. It’s a fact that still doesn’t receive enough credit, and Japan was one of the countries that helped drive our own culture forward.

The greatest impact Japan had was on the French school of Post-Impressionists. After Japan had to end its long isolationist period in the 1850s, they began to interact with the west both economically and diplomatically. Japanese culture and aesthetics, which Europeans knew little about, became a massive trend. Much like Chinoiserie in the eighteenth-century or the Spanish revival in the 1860s, Japonisme was picked up by artists as source material.

The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam explores one such connection between Japan and Vincent van Gogh. Titled Van Gogh & Japan, the exhibition explores the innovation of the Japanese, along with Van Gogh’s own evolution as an artist when he first encountered traditional woodblock prints in Antwerp and Paris.

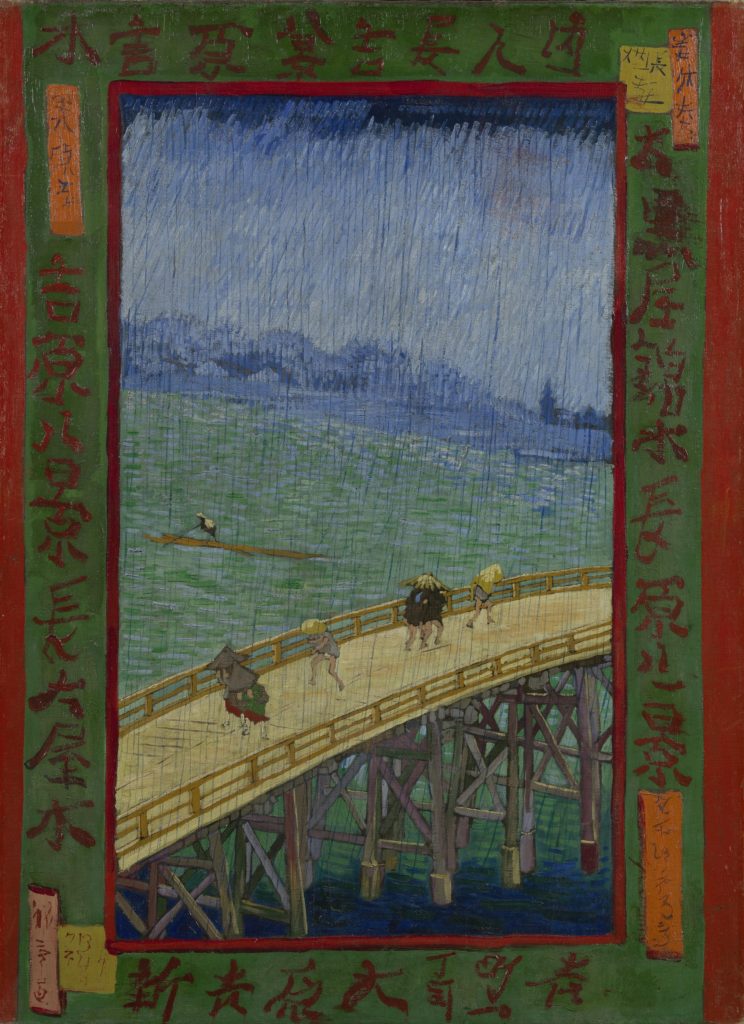

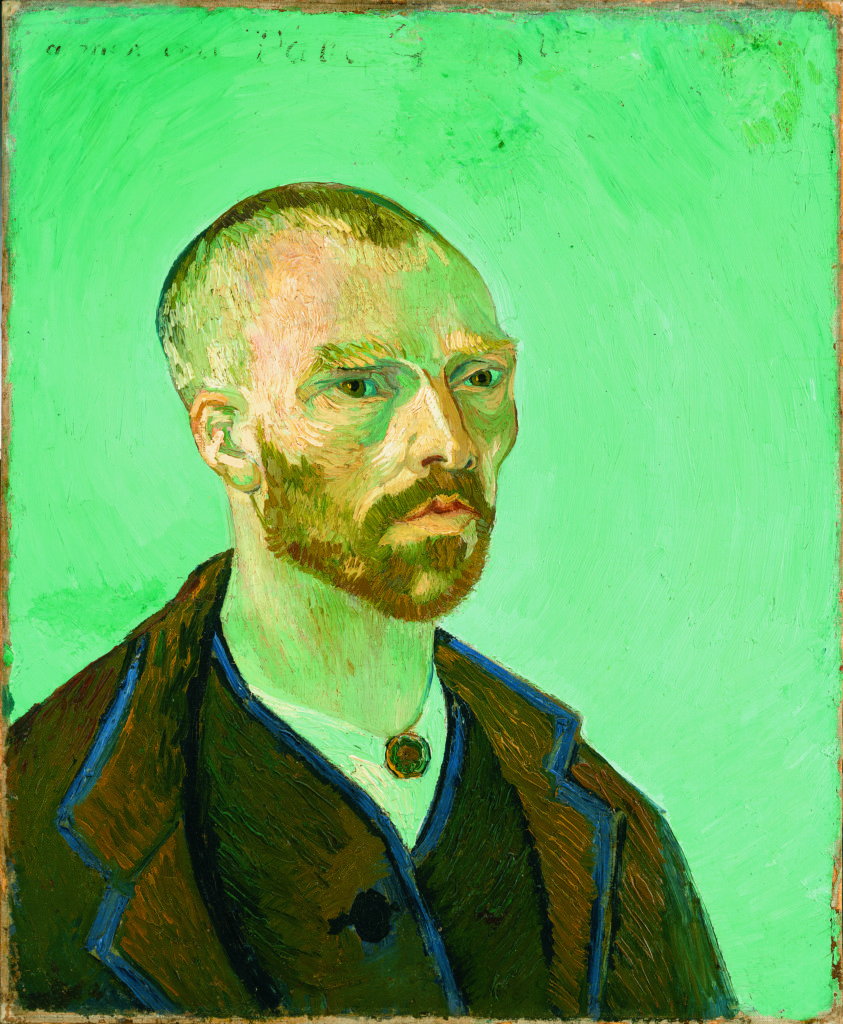

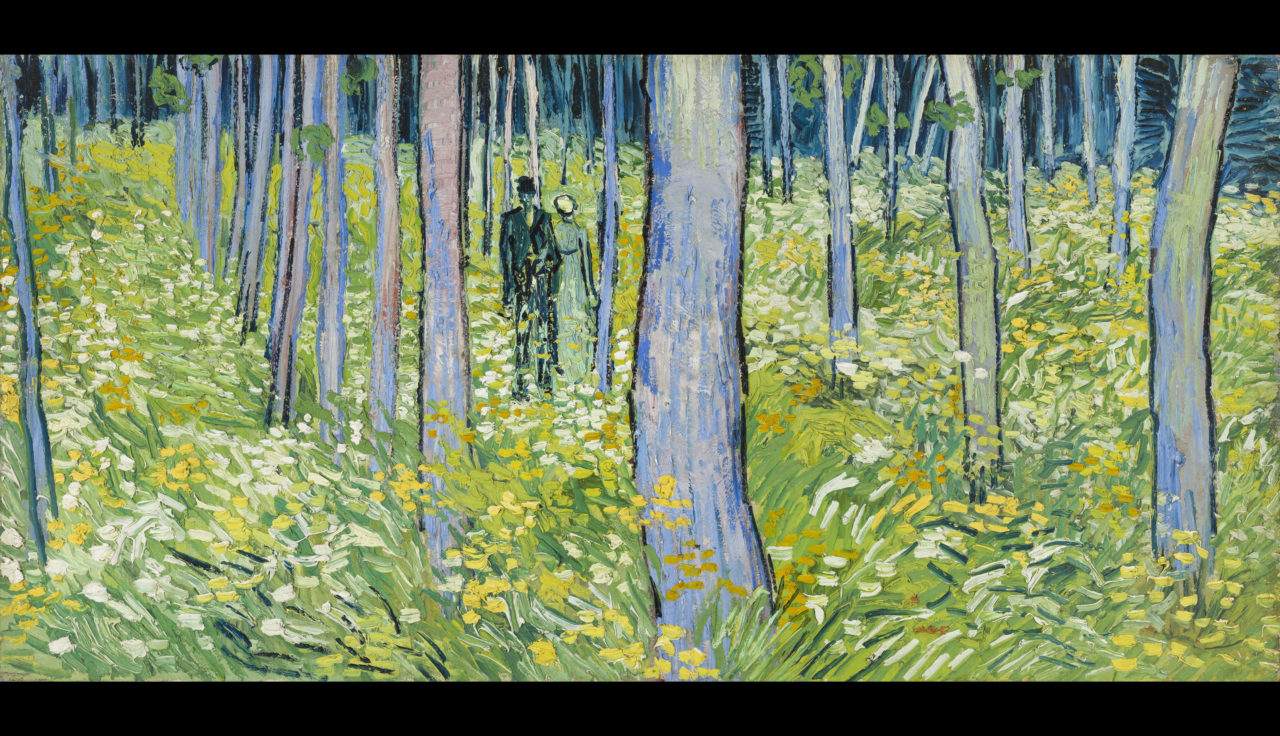

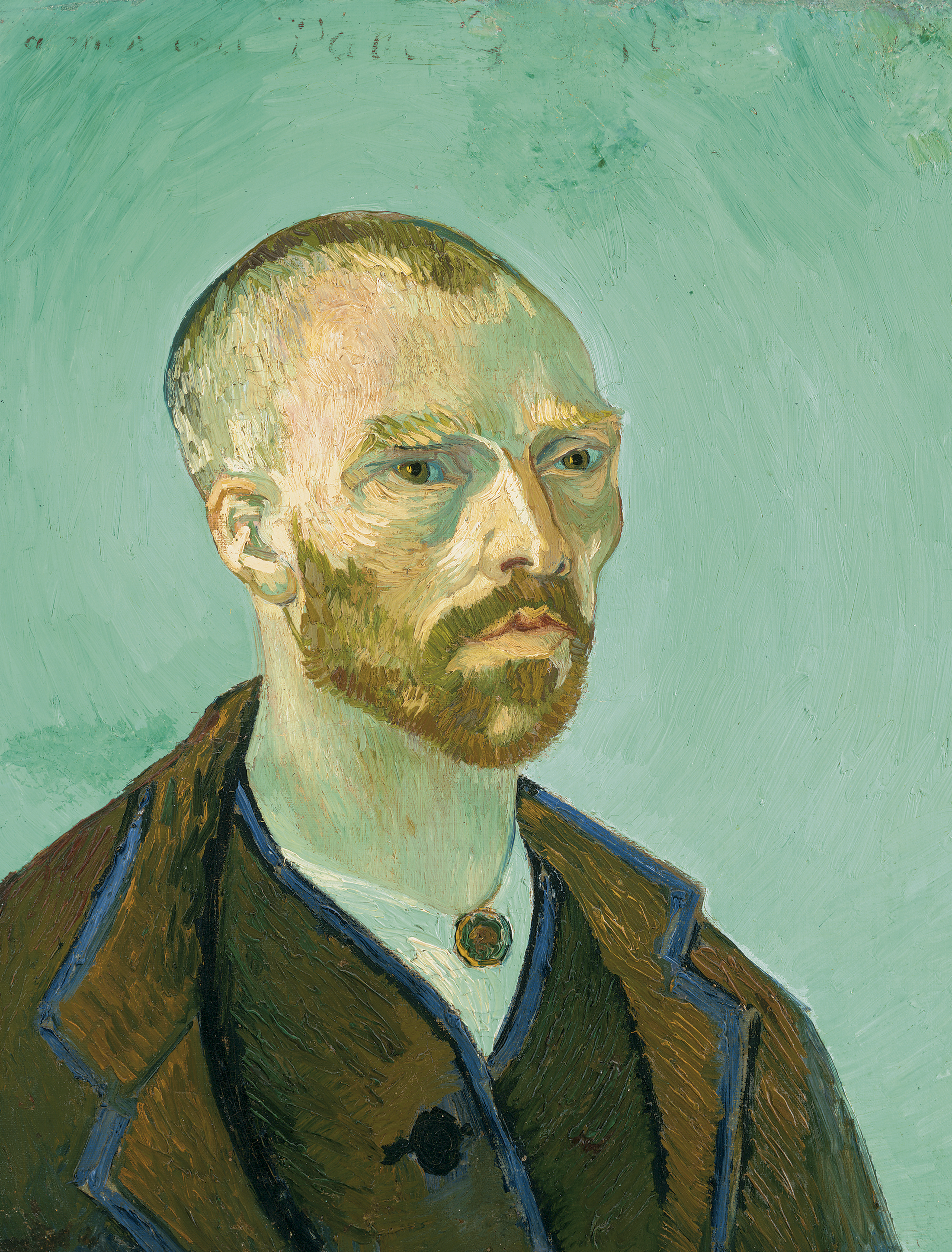

Van Gogh was struggling to find a voice in his early years, and these prints are framed almost as a revelation. He eventually collected hundreds of these prints by the 1880s, which were affordable and easy to transport. He even decorated his home and studio with them. Throughout the show, his scenes of forests and landscapes are the most obvious in their homage to the flat planes of colors, bare middle grounds, and irregular compositions found in prints by Hokusai and Hiroshige. However, his rendition of Japanese prints and his own portraits, which feature flat color or pattern also imitate Japanese woodblock printing.

What is most admirable about this exhibition is how Van Gogh never seemed to condescend towards foreign cultures quite like his contemporaries. One shudders when thinking of Paul Gauguin’s treatment of Tahitian women, and his racist and sexist views regarding “primitive cultures.” Picasso was not much better towards African and Oceanic cultures a generation later.

However, for Van Gogh, the Japanese were to be venerated. This is not an excuse for a European man looking at a country (via colonialism) that he never visited and probably never would have understood. However, the paintings themselves show that instead of directly stealing from the Japanese, Van Gogh’s mind seemed to open up. He could finally delve deeper into his more radical ideas concerning painting, like flattening the picture plane, enriching his color palette, and abandoning traditional methods of composition altogether. If the Japanese were allowed to do it, why couldn’t he do it, too?

Van Gogh & Japan is a reminder of how positive a cultural dialogue can be. After all, many of Van Gogh’s paintings might be masterworks because of his exposure to Japanese artists and craftsmen. With that said, it is also important to see this show as an appreciation and recognition of non-western art and culture. Although the latter half of the twentieth-century worked to change the art historical canon, western supremacy in the narrative persists. It is always hopeful to see institutions attempting to create equality in that narrative.