Grand Scale

Epic Abstraction at the Met

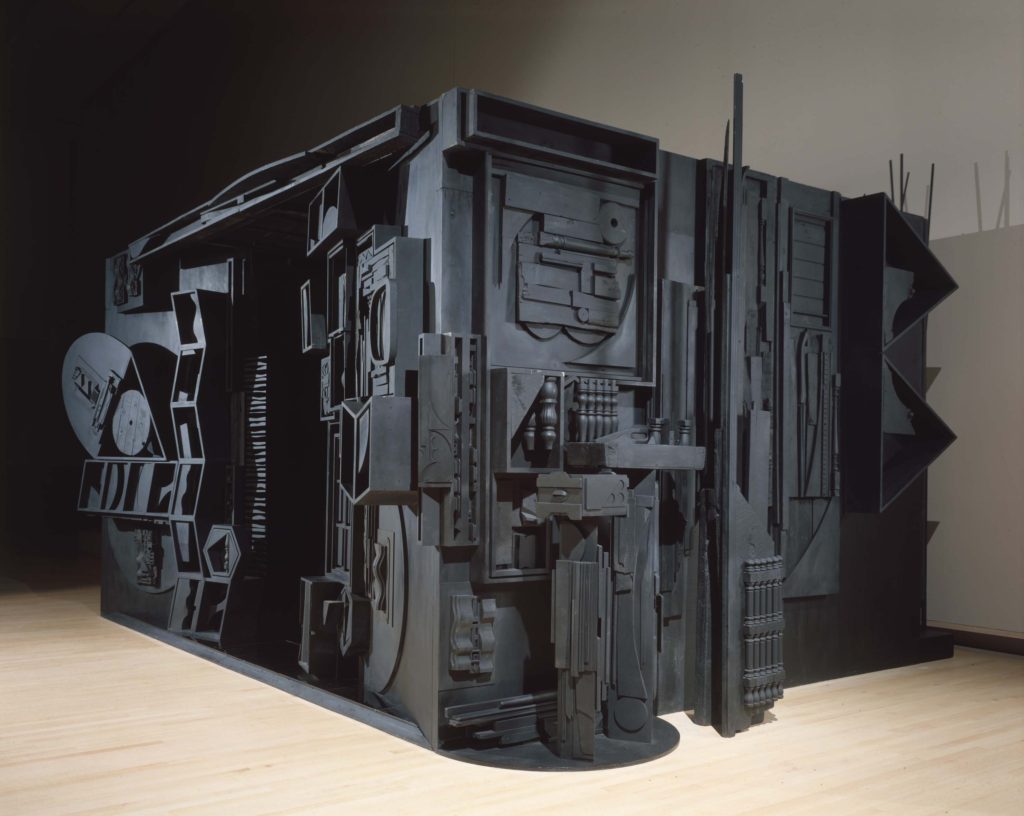

Abstract art after World War II was a discussion often dominated by white, male, mostly straight painters. It can feel like a rehash to explain and exhibit Abstract Expressionist or Minimalist canvases for the umpteenth time, but thanks to a long-term exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, post-war abstraction still offers moments of surprise and wonder. With the flashy title of Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera, classic works from the 1940s and ‘50s mingle with works that might not be as well-known, presenting an intriguing dialogue not often found in the pages of your art history textbook.

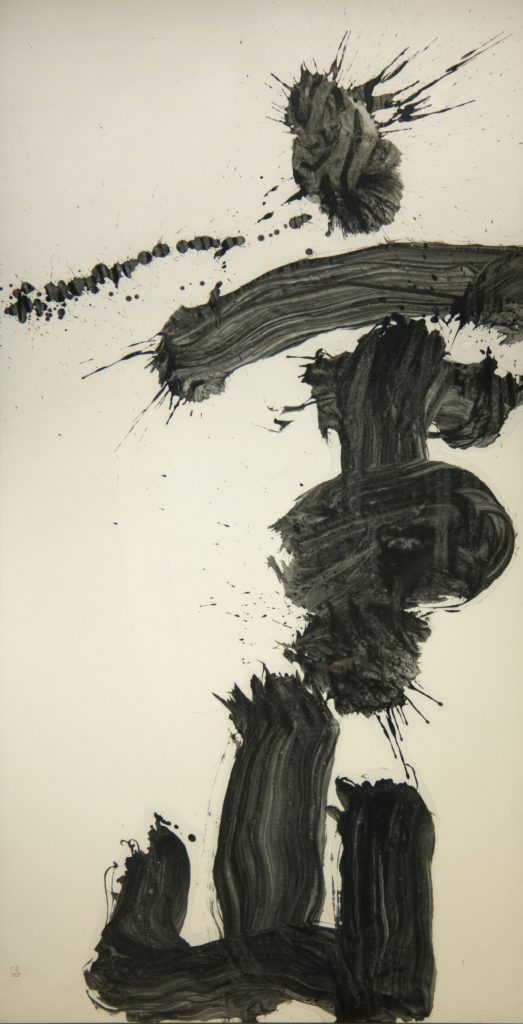

Beginning traditionally enough with Jackson Pollock as a jumping off point, this show eventually diverts into new territory. Since the Met is drawing from impressive works in its own collection, it makes sense to include iconic works by Mark Rothko or Willem de Kooning, but the real treasures are the works viewers haven’t yet had a chance to see. Pollock, rather than just being shown with the usual AbEx subjects, is shown next to Japanese artist and Gutai member Kazuo Shiraga or the late, great Hedda Sterne.

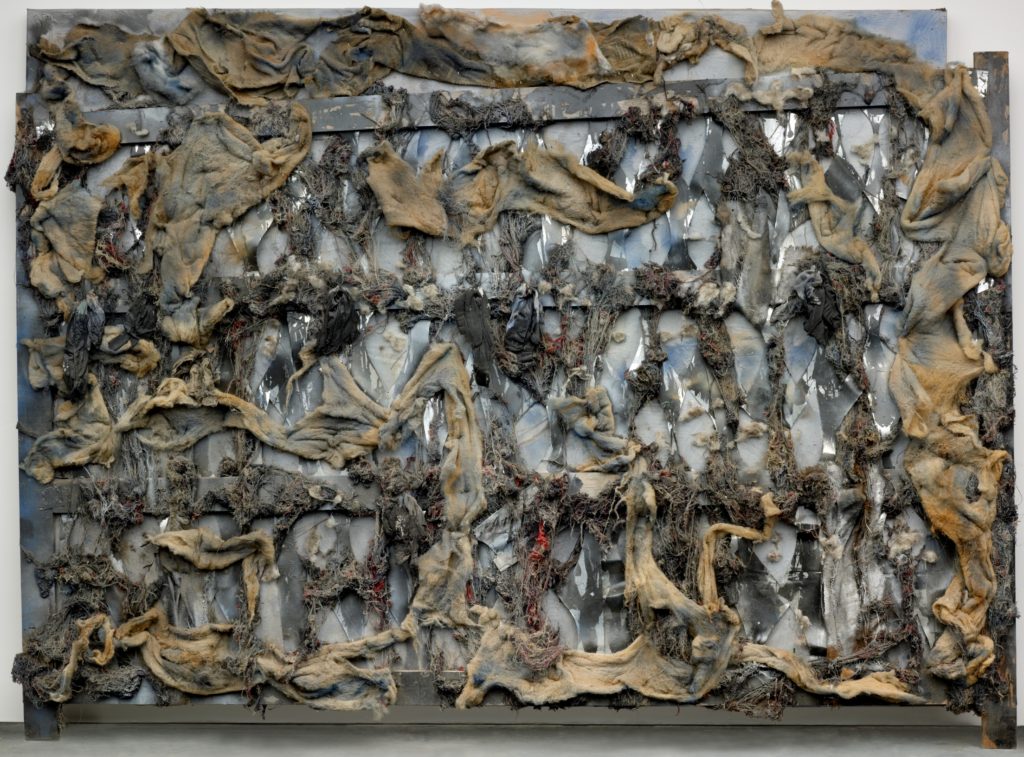

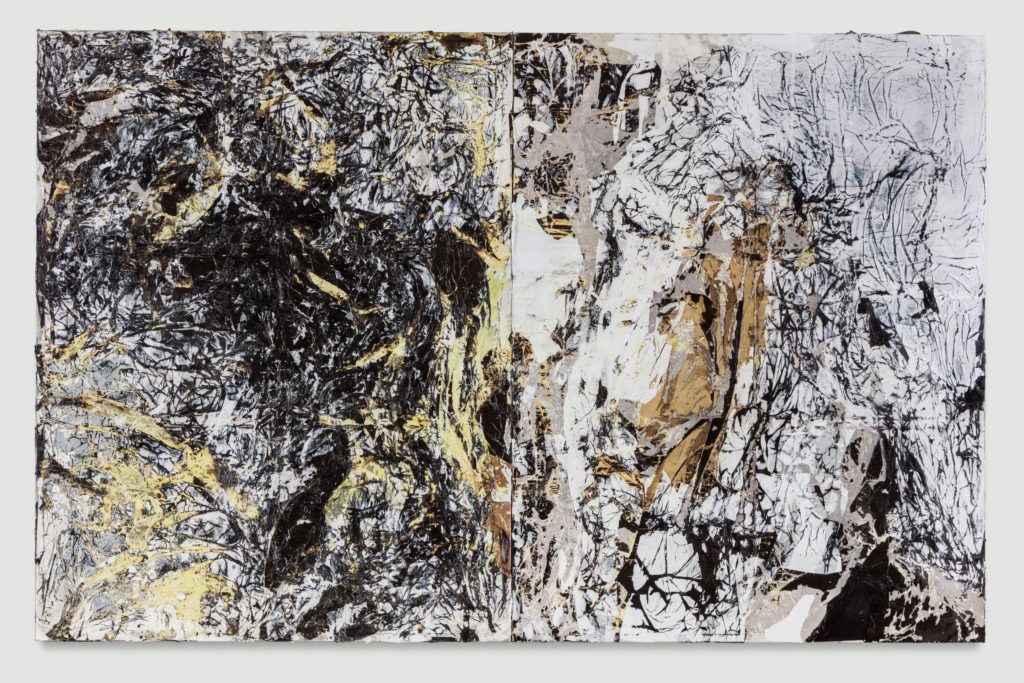

Artworks from the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries also find their way into this exhibition. A grandiose and wonderfully energetic canvas by Mark Bradford, titled Duck Walk from 2016, appears as if it is closely related to Abstract Expressionism. However, it abandons that’s movements rejection of narrative or history. With its title, Bradford references both Chuck Berry and voguing from the ballroom scene, both hallmarks of African American culture. This canvas repositions itself as a celebration of an often ignored group of artists and producers of culture.

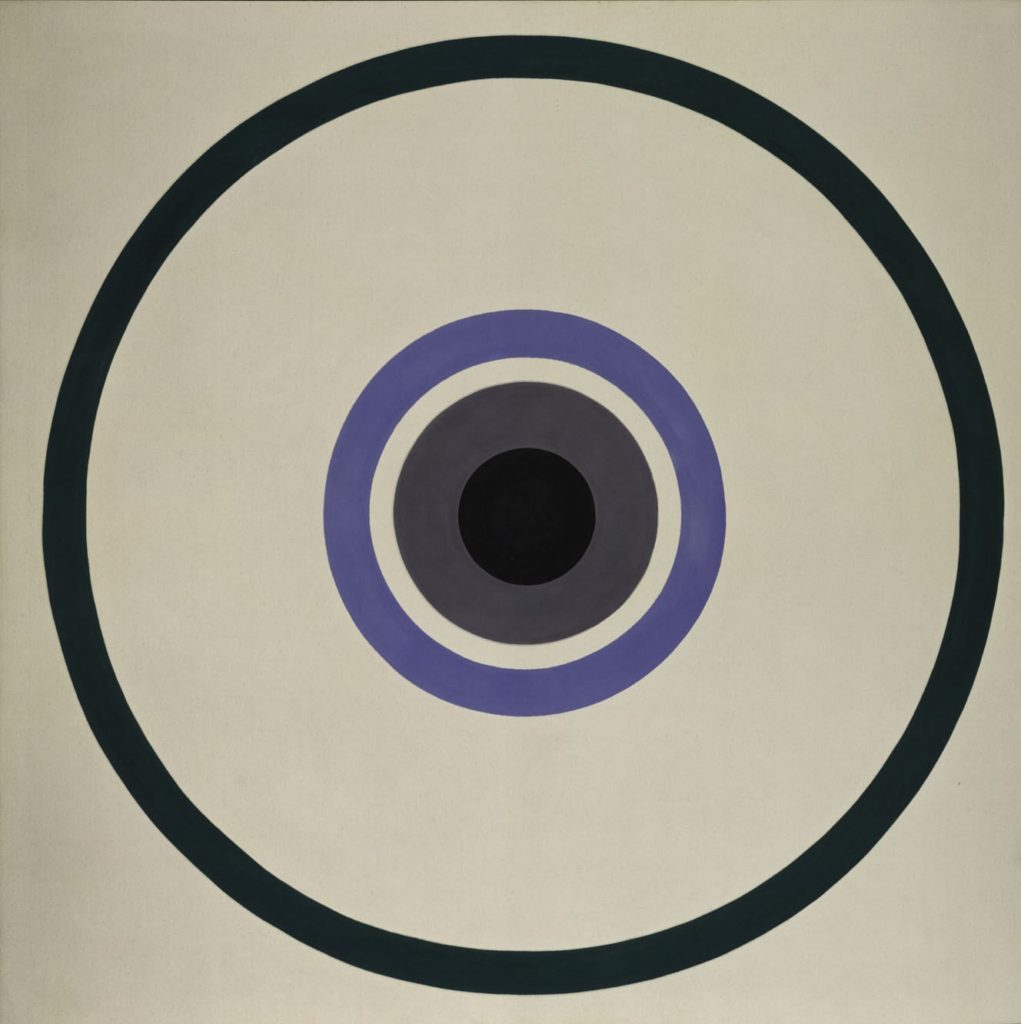

Also bringing about a more diverse melding of style and history is Ilona Keserü. This Hungarian artist bridged the folk art and craft of her culture with western abstraction. Wall-Hanging with Tombstone Forms from 1969 is a perfect example of this mix in styles. Although making reference to her world, this piece would look right at home next to Bridget Riley or Ellsworth Kelly. Keserü also used her art practice to her benefit: by using certain traditionally Hungarian styles, she flourished and avoided suspicion by her country’s government in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

Epic Abstraction isn’t simply an exhibition that shows off the greatest hits from the post-war era, it actually provides context and a broader cultural understanding of abstraction beyond New York. Since Jackson Pollock achieved critical success, the narrative of abstraction has always been one of American dominance and genius. However, this show illustrates that Abstract Expressionism or Minimalism were not simply mythical inventions, but a series of exchanges and evolutions of ideas being practiced all over the world.