Man Ray Rayographs

Man Ray’s radical Rayographs at Yale Gallery’s “Everything Is Dada” exhibit

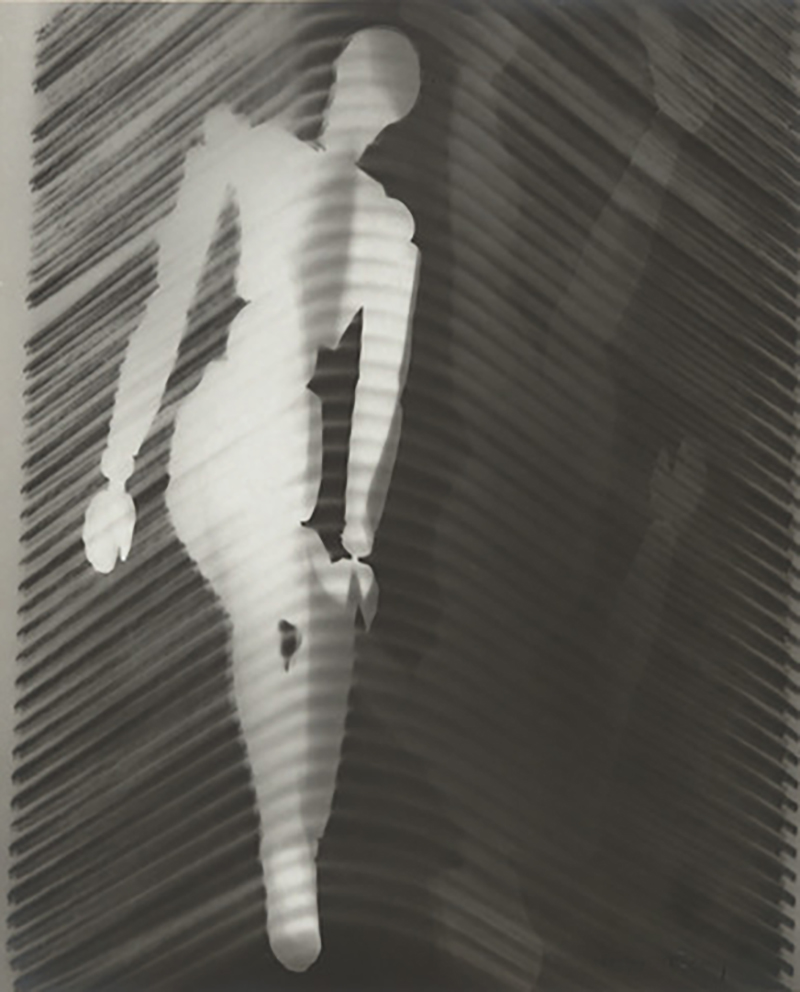

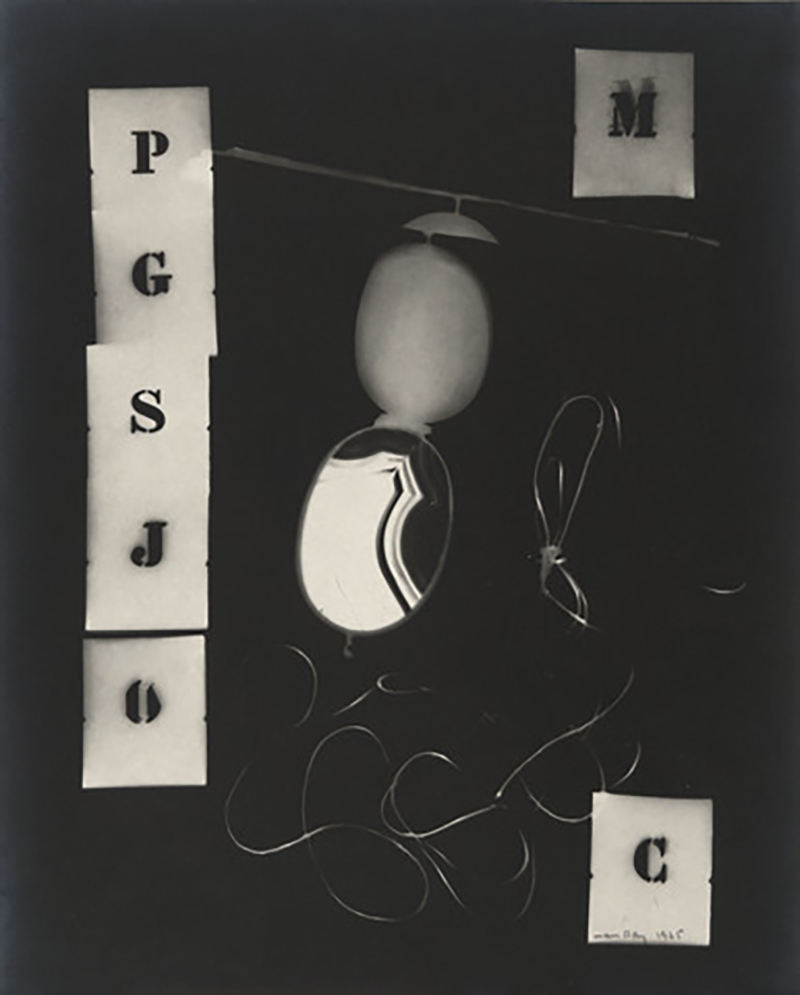

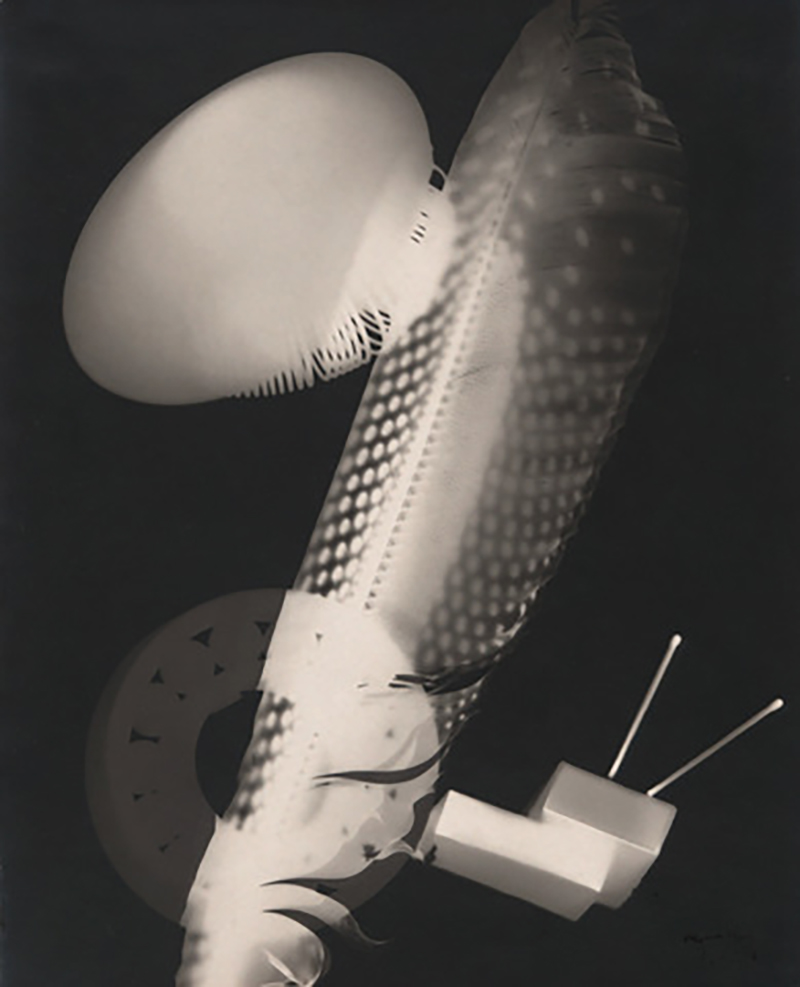

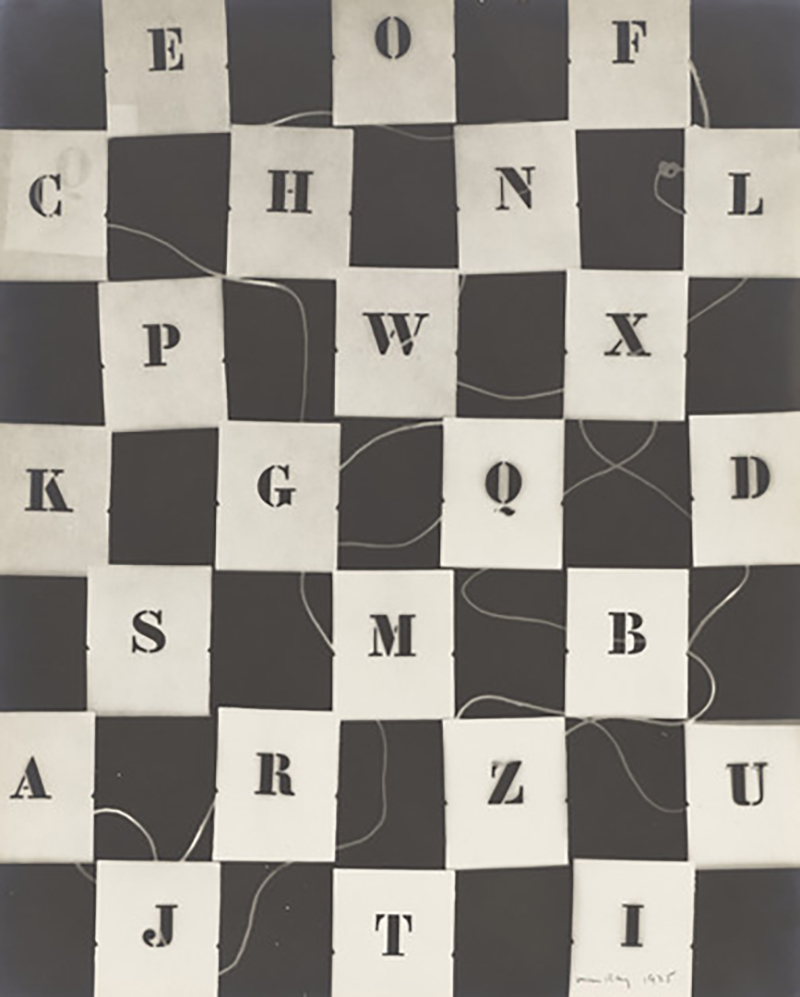

“Rayographs” were actually photographs of an unusual sort: these radical new Dada images were made by the American expatriate artist Man Ray in Paris in the 1920s without a camera or lenses. Instead, he placed a variety of objects—discs, coils, manikin cut-outs and other odd forms—on photosensitized paper and exposed the paper to light. The effect is similar to that of an X-ray or photographic negative: objects that were opaque and blocked the light show up as white and those that are more transparent appear more ghostlike. The process is similar to the one used in the 1950s by Susan Weil and Robert Rauschenberg to produce their blueprints (or cyanotypes); Ray called his prints “Rayographs,” but the generic term for all these camera-less images is photograms. Another major proponent of the medium was the Hungarian-born photographer and painter Lászlo Moholy-Nagy.

Ray’s visionary Rayographs were embraced by other Surrealists and Dada artists for the way they elevated ordinary objects to the point of abstraction. Thus it seems only natural that the images below were included in the Yale University Art Gallery’s recent epic exhibit, “Everything Is Dada,” which celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Dada movement, in New Haven, Connecticut, highlighted by PROVOKR here.