The Immense and the Intimate

Vija Celmins at SFMoMA

Do you think a small drawing could make you reconsider your own relation and awareness to something unquantifiable? Something as large as the ocean, or even outer space? A new retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art entitled Vija Celmins: To Fix the Image in Memory provides a convincing argument that, indeed, a drawing can do just that.

The subject of this exhibition, Vija Celmins, began producing her first major works in the 1960s. She painted everyday objects and newspaper photos, one example is the 1964 painting Heater, which of matter-of-factly shows a space heater glowing against a gray void. She also made sculptures, which were small objects made massive and vice versa. Things like pencils and combs became the size of a human, and typical suburban homes became the size of doll houses. All of the art Celmins produced at this time possess a certain coldness and emptiness. Violence also seems to be a common theme; Celmins renders a burning house into a play toy and her paintings of war planes are done in ghostly grays. There is an obvious influence of Pop Art in works such as these, but her escape from Europe shortly after World War II might suggest autobiographical hints, too. However, by the end of the ‘60s, Celmins made a shift. She moved beyond just objects, and went on to more immense subject matter.

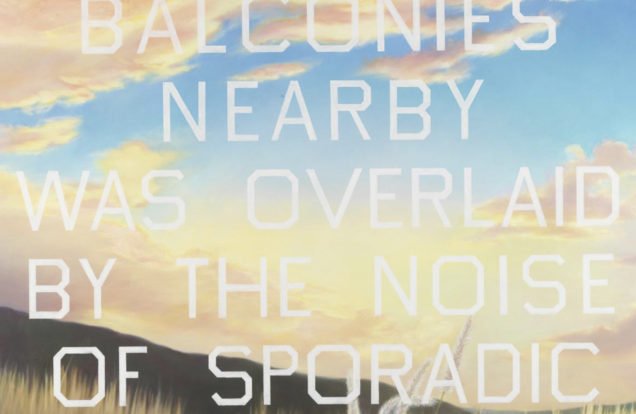

Scale is a recurring theme throughout all of this artist’s career, but it truly came into its most beautiful form after 1970. Clemens began focusing primarily on creating small, highly detailed drawings. A starry night, the waves of the ocean’s surface, planets, and clouds in the sky became her subject matter. Each drawing feels like a small jewel, with their compact size and extreme level of care. They also make something of incomprehensible scale seem intimate, soft, and graspable. Most of these drawings that Celmins made are done so that the viewer has no point of reference to the horizon, thus making scale and context suddenly feel very subjective. Celmins also studied the minute subjects of spiderwebs, rocks, and seashells. Again, the lack of any surroundings in these drawings makes scale feel indeterminate, even useless.

In all of her work, Celmins manages to push her photorealism to a point of near total abstraction, which is very important to note. By doing this, Celmins pushes viewers to reconsider their own perception of scale and relation on the most universal terms. To do something so profound with a pencil on a small sheet of paper is masterful, and this exhibition is a showcase for these subtle but commanding skills of Celmins.