DOUBLE FEATURE 08.21.20

Female Trouble: Body Heat + Widows

Five years after the heralded 12 Years A Slave swept the awards circuit, director Steve McQueen followed up with 2018’s Widows, a sullen crime-thriller based on a British TV series from 1983 and co-scripted by Gone Girl author Gillian Flynn. After their husbands die during a heist gone wrong, three widows, played by Viola Davis, Michelle Rodriguez and Elizabeth Debicki, are forced to come up with the cash their men stole, so they team up to commit a robbery. At first glance, Widows is a straight-up heist film. But McQueen manages to pack its subtext with commentary about race, politics and sexism without sacrificing screen action, giving the movie a heft that takes it well beyond the tropes associated with the genre. Like the iconic Thelma & Louise, with which director Ridley Scott shattered the mold and subverted expectations that come with the women-take-matters-into-their-own-hands plot, McQueen manages to defy convention and delivers a satisfying, unpredictable film with powerhouse performances by its leading actresses.

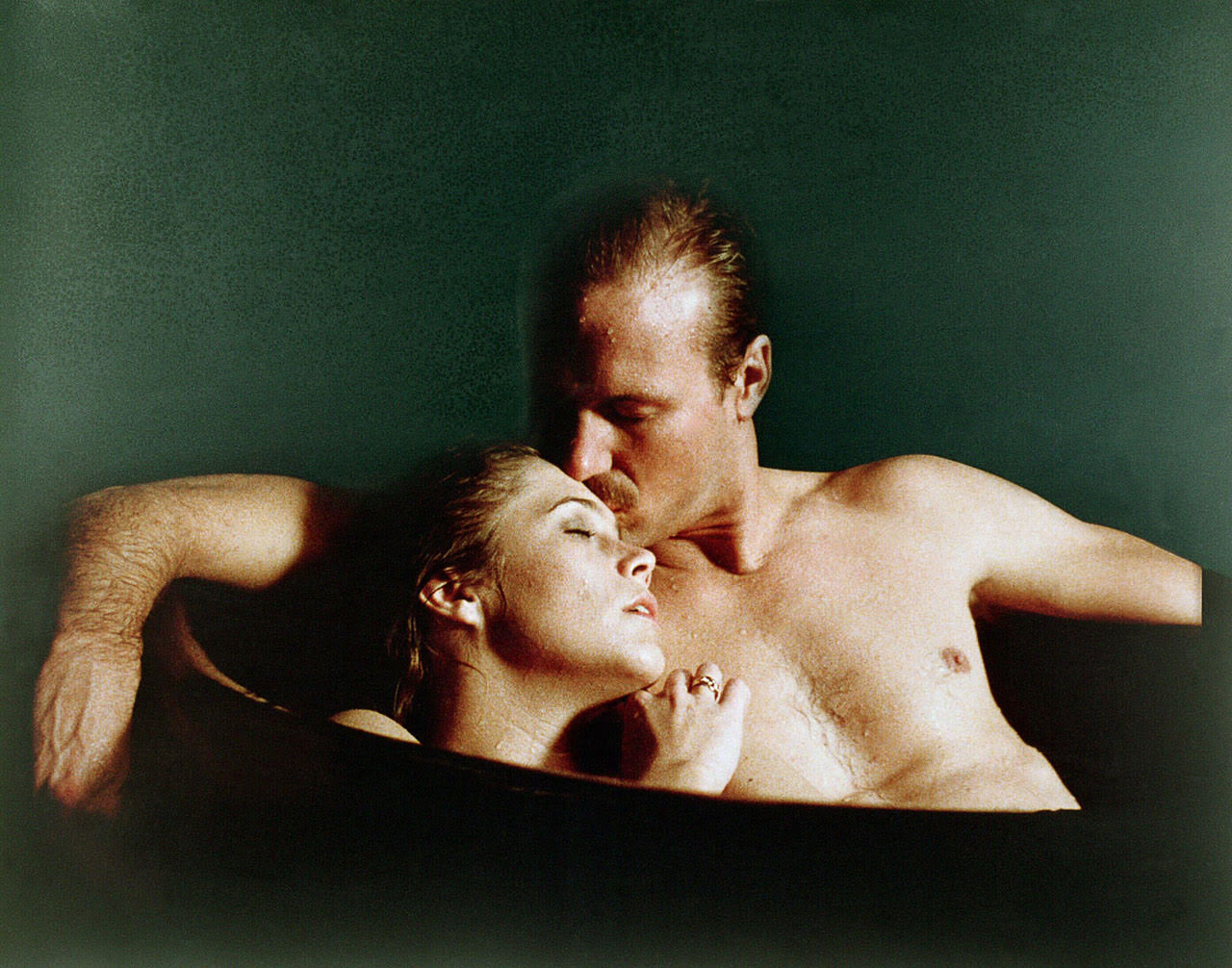

The femme fatale archetype goes as far back as the written word. The subject of myriad books, myths, plays, paintings and operas, she is strong, alluring, knows it and uses it to her advantage to get what she wants from men. In the MeToo movement era, the traditional femme fatale character has rightfully met her end, or at the very least has been revamped to represent female empowerment. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, however, the femme fatale was a staple of film and literature, often as the object of desire in gumshoe novels and noir films from the 1920s through the ‘50s, the most famous example being Double Indemnity, Billy Wilder’s brilliant 1944 noir starring Barbara Stanwyck as the seductress. That film inspired countless others, notably Body Heat, Lawrence Kasdan’s 1981 erotic neo-noir featuring William Hurt and Kathleen Turner in her screen debut. Of Turner’s breakout performance, Roger Ebert wrote, “Turner … played a woman so sexually confident that we can believe her lover could be dazed into doing almost anything for her.” While a lot of ‘80s films have aged poorly — many are unwatchable — Body Heat manages to transcend its decade, mainly due to the level of film-craft. Turner and Hurt’s stellar performances aside, the film’s stylized atmosphere, score and cinematography complement one another perfectly. Sensual and sexually graphic as Body Heat is, there is nothing gratuitous about it, making it challenging to write it off as sexist or manipulative, despite the presence of an old-fashioned femme fatale.