DOUBLE FEATURE 11.20.20

Film Noir: Memento + Laura

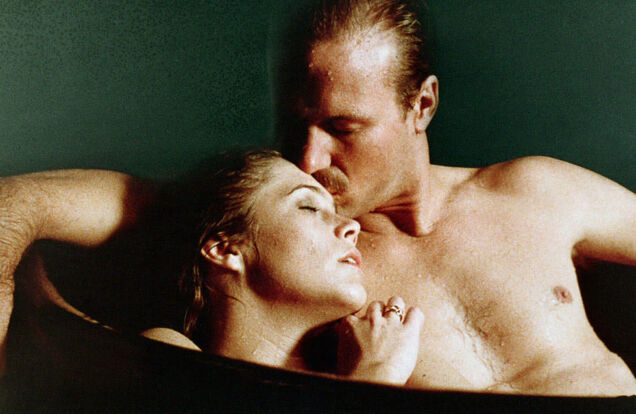

About halfway through Laura, Otto Preminger’s seminal film-noir classic, there is a scene in which Detective McPherson (Dana Andrews) is alone in Laura’s apartment. She was murdered, and he is the case investigator. By now, he had interrogated all of the suspects and had a relatively complete picture of the victim. Making himself comfortable, McPherson loosens his tie and takes off his jacket. He pours himself a brandy and wanders into her bedroom, where he pokes around in her lingerie drawer, smells her perfume, and opens her closet. McPherson then takes the bar’s brandy bottle and sits in an easy chair by the fireplace, near Laura’s portrait. As he falls asleep, the camera zooms into a close-up of his face — the liquor bottle is in the shot as well — and then slowly pulls out from him without cutting to another image. Off-screen, we hear the apartment door open and close. McPherson awakens to see Laura standing before him. He tries to process the moment: is he dreaming, or has the corpse come back to life?

It is an ingenious scene that makes Laura stand out among some of the greatest noirs ever made. Laura doesn’t contain many of the noir genre’s cinematic tropes — canted angles, dark shadows, etc. Laura seduces McPherson, but she is not a typical femme fatale, primarily because she is dead or presumed to be. As one of the primary suspects says to McPherson just before the sequence, “You better watch out. McPherson, or you’ll end up in a psychiatric ward. I don’t think they’ve ever had a patient who fell in love with a corpse.”

What McPherson falls in love with is not a woman, but a composite of one made up of details he’s learned from the suspects, all of whom were in love with her as well. Laura is an object, a product of the male gaze, a concept ahead of its time. The term only entered the feminist lexicon about thirty years later, in the 1970s. While Jean-Paul Sartre wrote about the philosophical notion of the gaze in his existentialist masterpiece, Being and Nothingness, he didn’t specify it as exclusively male. However, it is hard to overlook the timeline of the book’s publication and the making of Laura — 1943 and 1944, respectively, leading one to believe that Preminger was up on philosophy.

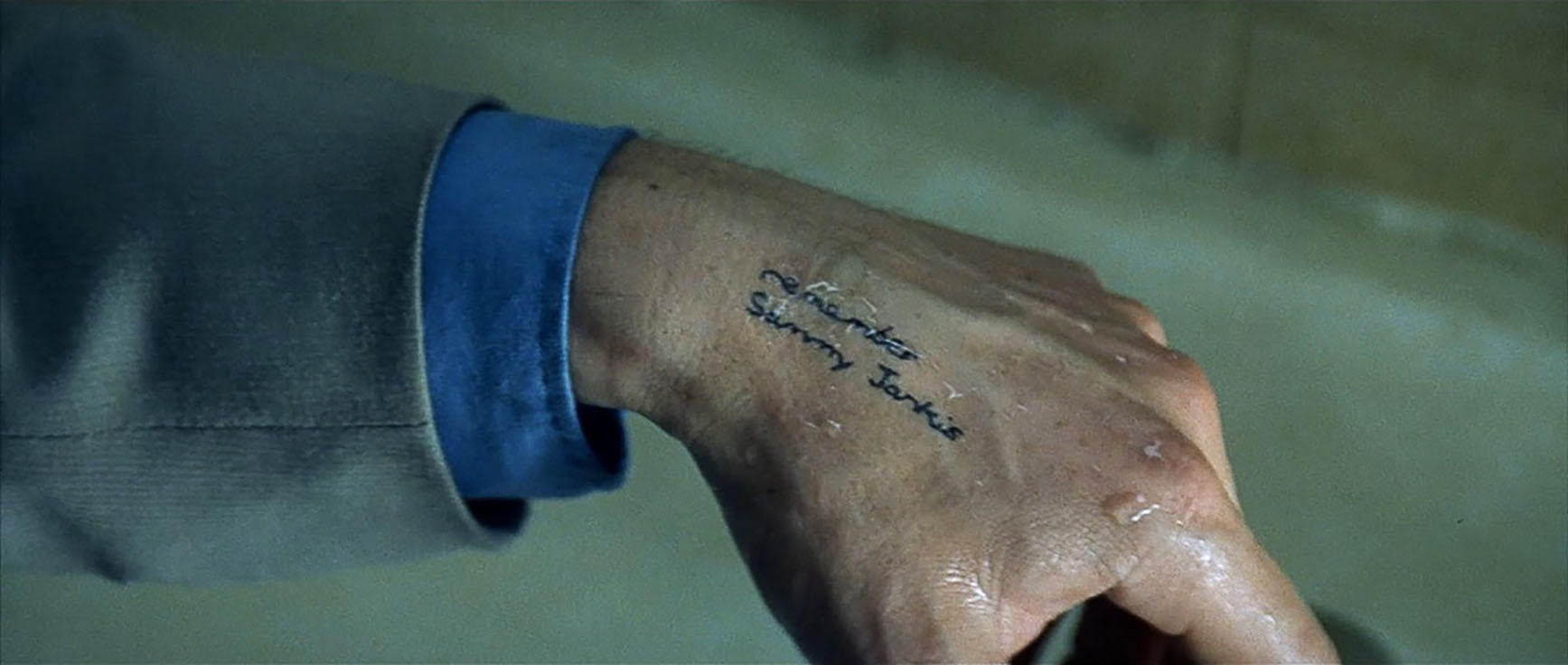

Another unusual noir film that plays with the genre and subverts expectations is Memento, Christopher Nolan’s second feature film from 2000. It’s the movie that put him on the map as a formidable director. As with Laura, which opens with her portrait’s image over the credits, Memento begins with a Polaroid photo, on which the entire plot hinges. As we watch the picture, however, the image on it fades away as the hand holding it shakes it to develop it, which clues us that we see the action in reverse. It is a perfect opening metaphor, as Lenny, the protagonist of the film, played by Guy Pierce, has an affliction that renders him unable to create new memories — they fade away from his mind right after they occur. The last thing he remembers is his dead wife, which set him on a course to track down her killer. Because he cannot retain any memories after her death, he takes notes and tattoos his body with the information he needs to remember. Lenny also has to rely on the word of the only two people in his life. I re-watched Memento soon after seeing Tenet, Nolan’s latest film. What was striking was the continuity of the director’s fascination with the movement of time, the slipperiness of memory, and the recurrence of specific images, including a bullet returning to the gun that fired it. What was also interesting was the similarities to Laura. In both films, the protagonists have to rely on an image and the word of others for the truth–which may not be true at all.