Filming Being Charlie

From rehab to release, the saga of a screenwriter and Being Charlie

When preparing to go to the Toronto International Film Festival last fall, a PR rep for Being Charlie, the film I co-wrote, asked me how I’d gotten here. It was a tough question, and I had to think about it. No answer I gave him was going to make any sense.

It certainly didn’t make sense when I’d gotten that call back in February of 2015. I’d been temping in mailrooms and catering part time when word came down that Rob Reiner—the guy who had reinvented genres with When Harry Met Sally… and The Princess Bride, and had invented a whole new one with This Is Spinal Tap—would be directing the film I’d co-written. It wasn’t possible, I’d thought. People who push mail carts and dole out chili don’t get movies made. Then again, most things leading up to this film, including the very first draft, which I wrote with Nick Reiner, Rob’s son, in a Los Angeles rehab, flew in the face of logic. But after finding in Nick my creative soul-mate and learning the cathartic power of personal narrative as a result of getting thrown out of college and into a drug and alcohol treatment center, you kind of learn to roll with it. I got on the first plane I could, and for the next three months watched the whole production in various states of awe and disbelief.

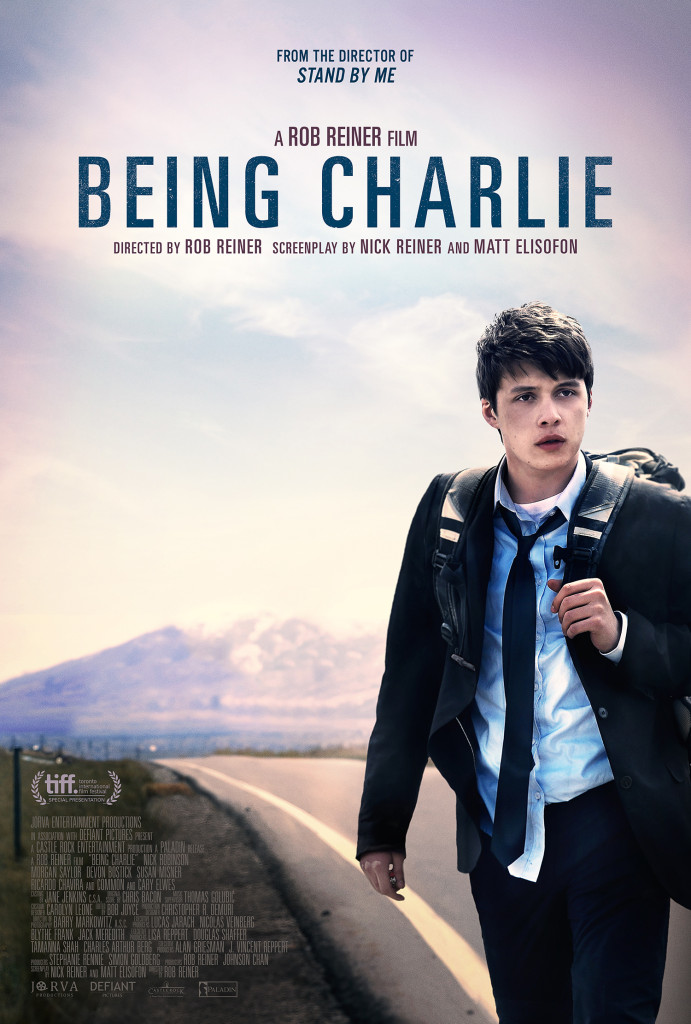

Casting the movie brought it a little closer to reality. Living, breathing, above-average-looking humans began to come in and read for parts we’d made up. Our first selection was Devon Bostick (from the CW series The 100) as the best friend; he nailed a poorly written line of ours that every other actor had tripped on. We figured that if he could make that terrible line sound good, he could do anything. Finding the titular lead for Being Charlie was a little harder. Nick Robinson (the kid in Jurassic World), who was running late, barged into the audition of another actor thinking that we were waiting for him. When he realized what he’d done, he flashed this baby-faced smile that seemed to evaporate any sort of annoyance he’d caused. Before he’d read a line, we knew we had our man. After rounding out the rest of the principals and finishing the rewrites, we flew out to Salt Lake City to shoot. I remember when we landed—Rob joked that the Salt Lake’s Jewish population had just quadrupled. Looking back, I think his guess might’ve been conservative.

If casting proved to be the “pinch me” moment of this dream-come-true scenario, the first day of shooting was the haymaker. It was an eight-page day (most films are lucky if they get three or four pages done per day) over several locations in the brisk Utah desert. Nick Robinson, eager to make the leap from child star to leading man, survived seven falls out of a truck, a slashed finger, and the lodging of hazardous chemicals in his eye after a hand-warmer exploded—all with that patented smile.

Although we shot it at a breakneck pace—a mere 20 days to be exact—it never felt that way. Rob managed never to cut in to lunch or overtime, a rarity even with a more generous schedule, and one night he even halted filming for two hours so the crew could watch the Mayweather-Paquiao fight before finishing up on time.

After hours and weekends during the shoot were surreal too. All the cast and crew stayed at the same Hyatt in downtown Salt Lake. Since the hotel didn’t have any food or room service, we all took over the lobby and ate take-out together—as if we were in some sort of satellite Hollywood kibbutz. And seeing as though late-night options were limited (it was Utah, after all), the under-30 cast and crew got creative in various hotel rooms and parking-lot roofs. As clichéd as it might sound, we became a tight-knit family when we wrapped for the day.

When we finally got to the last shot, a new sort of disbelief set in. Just as I was getting comfortable with the camp-like routine of life on location—and nearly accustomed to watching my story get made—it ended, as abruptly as it started. Once again, I found myself in an unfamiliar place with no real understanding or recollection as to how I’d really gotten there. So, after mulling over the PR rep’s question in Toronto about how I got into writing movies, all I could do was shrug and say, “I went to rehab.”