MINORITY REPORT

A Tale Of Two Hollywoods

Actress Hattie McDaniel didn’t set out to make history when she was cast in the part of Mammy in MGM’s classic, Gone With The Wind, but she did. Stepping up to the microphone in the segregated Ambassador Hotel to accept the 1939 Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress, she became the first African American to be honored with an Oscar. With the statuette in hand, she was at once both an unintentional and instantaneous trailblazer, but as she told the audience, she only hoped, “That I will always be a credit to my race and to the motion picture industry.”

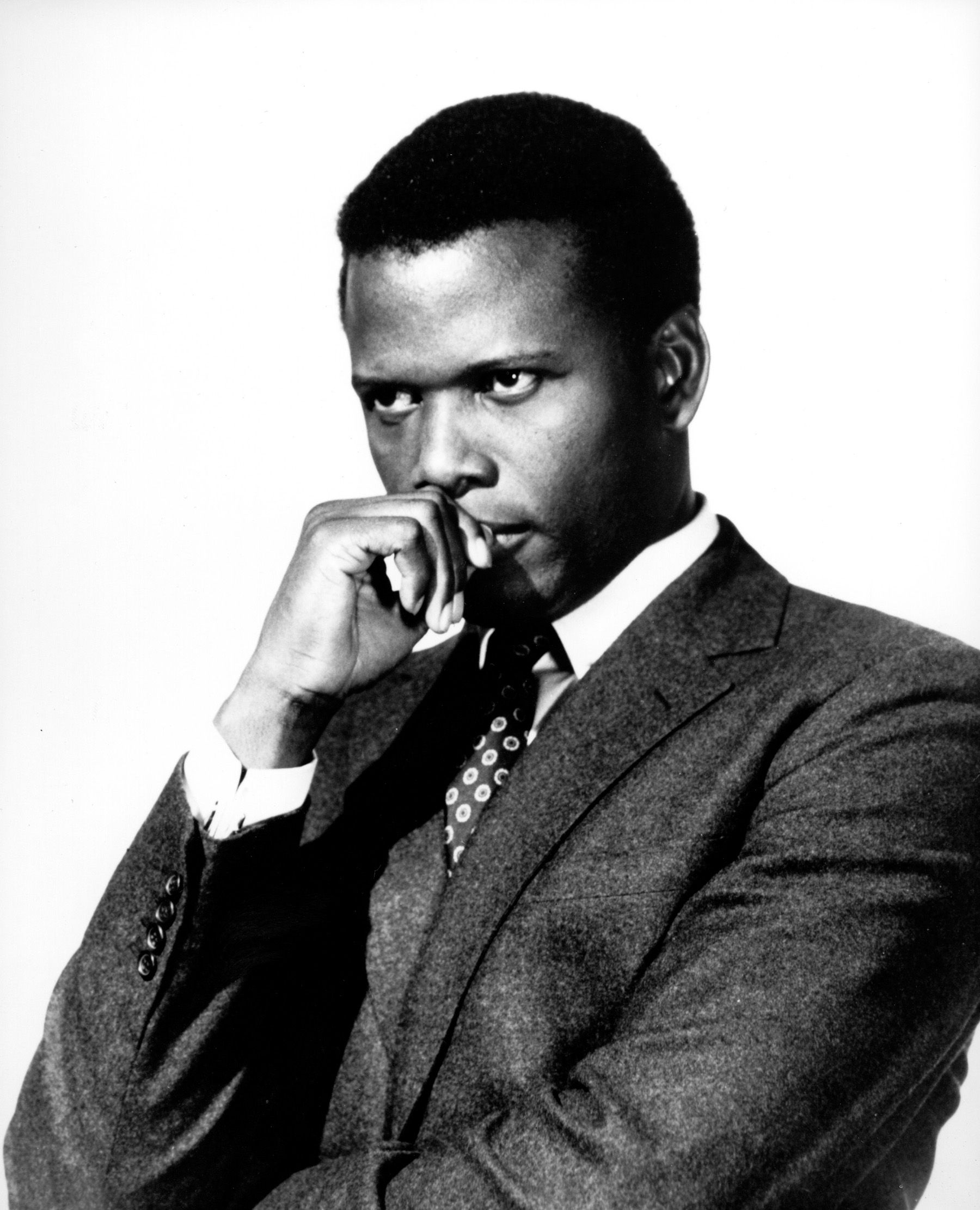

She was both of those things, and while she broke the race barrier, it would be 24 years before the next African American, Sidney Poitier, won an Academy Award, and another 8 before Isaac Hayes became the third black honoree and the first in a non-acting category. While regrettable that it took 12 years for the first person of color to be recognized by the Academy, there would be another 9 Oscar ceremonies before Jose Ferrer, the first Latino winner, took home the Oscar for his 1950 portrayal of Cyrano De Bergerac. As surprising as these factoids are, perhaps the most shameful is that in its 92-year history, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has only nominated five women in the Best Director category, and just one, Kathryn Bigelow (The Hurt Locker), has taken home that award.

Women weren’t always marginalized in the film business. In the 1910s, before the advent of the studio system and the heavy hand of censorship, women had a significant presence in the business, and not just in front of the cameras. In the days of two-reelers and slapstick comedies, stars like Mabel Normand, Pearl White, Ruth Ann Baldwin, and the first female mogul, Alice Guy-Laché, were acting, writing, directing and producing films. It wasn’t until the late 1920s and early 1930s when the movies started to really make money, that the infamous Hollywood boys club was forged. Made up of white men that have included the likes of Louis B. Mayer, Jack Warner and Harry Cohn, some 100 years later, the business is still in the grips of testosterone-charged executives.

Oscar diversity hit a low point in 2016 when, despite having a black woman, Cheryl Boone Issacs, at the helm of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, for the second year in a row all 20 actors nominated in the lead and supporting categories were white. The racially unbalanced awards spawned the #OscarsSoWhite controversy and resulted in a boycott by a number of high-profile celebrities including Spike Lee, Will Smith and Jada-Pinkett Smith.

In the face of mounting criticism, the Academy made a concerted effort to diversify their rank and file — 32% of its members are now women and 16% are people of color. Yet despite those increases and the fact that some of the most acclaimed movies of 2019 were directed by women, not one woman was nominated for Best Director. Even Greta Gerwig, whose film, Little Women, was nominated for Best Picture, was overlooked for consideration as director. In the Academy’s long history, 12 female-directed films have been nominated for Best Picture but the women behind the camera of those films have only been nominated 3 times. It begs the question, does a movie worthy of Best Picture Oscar consideration direct itself?

It seems appropriately ironic that in the midst of such a polarized Oscar season where there was more diversity in the Oscar presenters than in the awards themselves, UCLA has released its 7th annual report on Hollywood Diversity. Co-authored by Dr. Darnell Hunt, Dean of the Division of Social Sciences at UCLA and Professor of Sociology and African American Studies at UCLA, and Dr. Ana-Christina Ramon, Director of Research and Civic Engagement for the Division of Social Services at UCLA, the study explores the relationship between diversity and the all-important bottom line in the Hollywood entertainment industry.

As Dr. Ramon recalls, “We were meeting, talking about the struggle creators of color experience, and thought it would be important to do some sort of accounting as to what was going on with the industry.” When they met with studio executives involved with diversity and inclusion, they were told while their work was important for the social good, the industry was not going to pay attention unless they could connect it to the bottom line.

Various advocacy groups had been doing report cards on the industry for a number of years, but they all were developed with studio-provided information. Not wanting to put the wolf in charge of guarding the hen house, UCLA chose not to rely on supplied data about headcount and the presence of minorities behind the studios’ well-guarded gates.

Reacting to the advice of the diversity executives they had met with, their goal was to show the connection between diversity and box office success. “We found out that diversity sells,” Dr. Ramon reports. “Regardless of the ethnicity of the household, people want to see diversity.” People of color, representing more than 40% of the US population, accounted for the majority of ticket sales for 8 out of the 10 top films. With numbers like that, the so-called minority audience is going to shape a lot of demand.

The UCLA report, aptly named, A Tale of Two Hollywoods shows that while considerable strides have been made in the realm of minority and female on-camera talent, progress behind the camera is less compelling, and it’s practically nonexistent in the executive suite.

Making up 50.8% of the population, women are the majority in the country, but not in the movie business. While the number of women as film leads increased 7.5% to 44.1%, they actually lost ground in the category of top actors, defined as the 8 actors who get top billing and are most influential to the storyline. Using those parameters, women represent 40.3%. Minorities, on the other hand, saw increases in both categories – up nearly 4% as film leads to 27.6%, and an impressive 23% increase as top actors. The advancement in minorities in being driven by black actors who, according to Dr. Ramon, “Are overrepresented in terms of their population numbers so they make up a lot of advancement in terms of people of color. The other groups including Latinx and Asians haven’t changed that much.”

The real difference for women is behind the camera where, despite making significant gains (women as directors more than doubled to 15.1% and as film writers gained nearly 3% representing 13.0% of all film writers), they are still outnumbered by men 3 to 1. Similarly, minorities saw nearly a 7% increase as writers to 13.9%, and a 24% decrease in the number of minority directors.

The largest disparity occurs in C-suite offices where films are greenlit and casting decisions are made. There, 91% of chairmen and CEOs are white and 82% male. Among the senior studio executives (Senior Vice Presidents and above) 93% are white and 80% male. Numbers like that beg the question, would there be more diversity in film if women and people of color held higher positions in the industry? Not necessarily. While the research shows that at the film level, a movie directed by a woman is likely to have more diversity in the cast and crew, at the studio level, where the path to the top is long and arduous, many women who achieve C-suite positions are unwilling to go against the grain in terms of the projects that are being greenlit.

There are exceptions, Universal’s Donna Langley is one of them. ”We see reflecting the audience we make our movies for in our movies to be good business.” With people of color accounting for more than 50% of domestic ticket sales for 8 out of the top 10 films, hers is a strategy more and more studios are adopting.

While casting minorities is the first step, according to the UCLA study, how they are represented on the screen is the most important consideration. “We often see films with diverse actors but the characters they are playing are raceless, or worse, one-dimensional stereotypical roles,” said Dr. Ramon. The industry doesn’t need colorblind casting, it needs stories and characters that are relevant to the ethnicities represented. Such specificity translates and lets other people find commonalities.

Fortune.com cites two films, Parasite, which surprised everyone by winning four Academy Awards including Best Picture, Best International Feature, Best Original Screenplay and Best Director, and the Indie Spirits Best Feature winner, The Farewell, as “achieving greatness by telling modern, specific stories about their communities that ultimately were stories about all of us.” The article went on to say that, “The characters were funny, sexual, bawdy and despicable, too – multi-dimensionality rarely afforded to non-white performers.”

With $11.4 billion in ticket sales, the United States had the world’s largest box office in 2019, but China, coming in at $9.2 billion, is catching up and doing so with homemade product. In fact, only two of the country’s top 10 grossers were American films (The Avengers and Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbs & Shaw). To give it some perspective, Japan is a distant #3 with a box office of $2.39 billion. If America intends to remain the leading exporter of movies to the world, it needs to modernize its worldviews. According to Dr. Ramon that means, “The studios really need to understand what the market is, and to change their practices to acknowledge it. And that message needs to come from the top.”