THE MOGUL WHO FELL TO EARTH

Don Rugoff & The Birth Of The Indie Movement

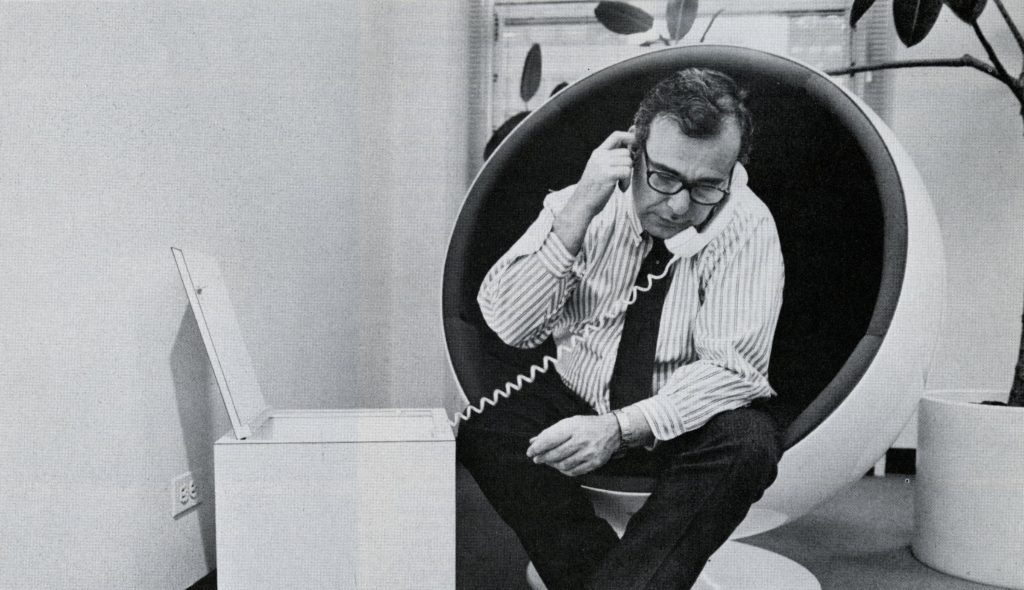

Before Harvey and Bob Weinstein, before Miramax, Fox Searchlight, Sony Classics, and all the other independent film companies, and a lifetime before Netflix, there was Donald S. Rugoff. Mr. Rugoff as he was called by anyone who ever worked for him. As head of Cinema 5 theatres and distribution, he was the father of independent film. Although his persona was anything but fatherly — he was famous for reducing his employees to tears — his influence on the business was unparalleled. His genes are the most dominant in the art house genome.

If you were alive in New York City in the last half of the 20th century, you likely visited a Cinema 5 theatre. Among them were the Beekman, Plaza, Paris, Sutton, Murray Hill, Gramercy, 8th St. Playhouse, the Paramount and the jewels in the Cinema 5 crown, the Cinema 1 and 2, arguably the most beautifully designed theatres in Manhattan. According to Richard Peña, the former director of the New York Film Festival, “When you went to see a film at a Cinema 5 theatre, you weren’t just going to a movie theatre, you were going to a film theatre.”

Rugoff’s attention to artistic detail made the theatres themselves destinations that both audiences and filmmakers loved. Mel Brooks insisted that his movies debut at the Sutton. Woody Allen would open his films only at the Beekman. The theatre was featured in his Oscar-winning masterwork, Annie Hall in a scene when a fan accosts Allen’s character, Alvy Singer, outside the theatre.

Rugoff’s devotion didn’t end with the design of the theatres; he was often spotted picking gum wrappers off the floor and checking to see that there was enough toilet paper in the bathrooms.

Being the most prestigious exhibitor in New York was not enough for Rugoff. He wanted to leverage the power of the theatres and elevate what movies Americans were seeing. So, in 1963, he began to acquire films. One might think that selecting movies for distribution would be a problem for a man who fell asleep as soon as the lights went down, but somehow Rugoff, who was rumored to have a metal plate in his head, was an ace at it. Exceptionally literate, he was drawn to the work of passionate filmmakers as opposed to the commercial fare that was coming out of Hollywood.

Director Ira Deutchman, whose documentary, Searching for Mr. Rugoff is celebrating its West Coast premiere at the Palm Springs International Film Festival, says it best, “What he was doing was manifesting the idea of film as art in a way that nobody else had ever done before and he wound up changing film culture in an enormously influential way.” Mr. Deutchman knows of what he speaks. A Columbia University Film school teacher; Deutchman worked for Mr. Rugoff from 1975-1978, moving on to become a film executive and founder of indie studios Cinecom and Fine Line Features.

Rugoff introduced great European directors to the American market, including Costa-Gavras and Lina Wertmüller. Rugoff championed Costa-Gavras’ political thriller, Z, which was nominated for multiple Academy Awards including Best Picture and won Best Foreign Film. Wertmüller’s Swept Away and Seven Beauties were both Cinema 5 releases, the latter earning Fellini’s one-time assistant director a place in the record books as the first woman nominated for a best director Oscar. “Without Rugoff the film would have been less important, less successful, but,” Wertmüller noted, “there was an element of madness about him.”

It would be easy to blame Rugoff’s bad behavior on the rumored plate in his head, but according to his family he’d always exerted a certain arrogance, the sense that he knew better than anybody about everything. Described by former Cinema 5 staff as reviled, feared, unpredictable, difficult, volatile and uncontrollable, he would think nothing about locking his staff in a conference room until they came up with a marketing hook for a film. He regularly had executives from his ad agency present concepts to him at the Edwardian Room of the Plaza Hotel, where he breakfasted every morning. Without ever inviting them to have a seat, much less a cup of coffee, he reviewed the concepts while dribbling eggs Benedict on his Lanvin suits and the presentation boards.

Beyond the bad behavior, there was genius, not just in selecting films, but marketing them. Says Deutchman, “Nobody would look back at the movies he bought and say they were the best movies ever made. He always picked them because he thought there was some hook there, something he could exploit. It was not just about putting it in a theatre, crossing his fingers and hoping that the reviews were good.”

With the aplomb of P.T. Barnum, Rugoff employed publicity tactics that hadn’t been used in decades. When Monty Python and the Holy Grail opened, he had actors (including members of his staff) dress up in Arthurian costumes and run down Fifth Avenue followed by a guy banging coconut shells that sounded like horses galloping. As if that weren’t enough, the first 100 people at the theatre were given free coconuts. The film, released in 1975, went on to be Cinema 5’s biggest hit, grossing over $7 million ($34 million in today’s dollars).

One wonders how Rugoff would market his own documentary, a highly entertaining history of indie film that Deutchman never set out to make. “I had been to a number of film festivals and industry parties and I kept running into the generation of people who had been in the business before me and realized that they were really getting up there in age,” he says. “People like Dan Talbot of New Yorker Films and Ben Barenholtz who opened New York’s Elgin theatre before founding Libra Films, and others who were contemporaries of Rugoff’s. I made up my mind that before those people disappeared, I wanted to try and get some oral history of that era. After a couple of interviews, Rugoff’s name kept coming up and I thought, hey wait a minute, I know something about that guy. I realized that he was the story.”

His is the story of the birth of independent films. Aside from esoteric foreign fare like Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes From a Marriage and Truffaut’s Soft Skin, Rugoff acquired hip counterculture films like Andy Warhol’s Trash and Robert Downey Sr.’s Putney Swope, of which he admitted, “I didn’t get it, but I liked it.” He wasn’t afraid to buy films that nobody else would take a chance on, such as Richard Benner’s Outrageous!, about a female impersonator who rooms with a pregnant schizophrenic. Deutchman says, “In 1977, nobody was releasing films like that. Certainly, there were gay characters in movies, but they were never treated as just normal human beings the way that they were in that film.”

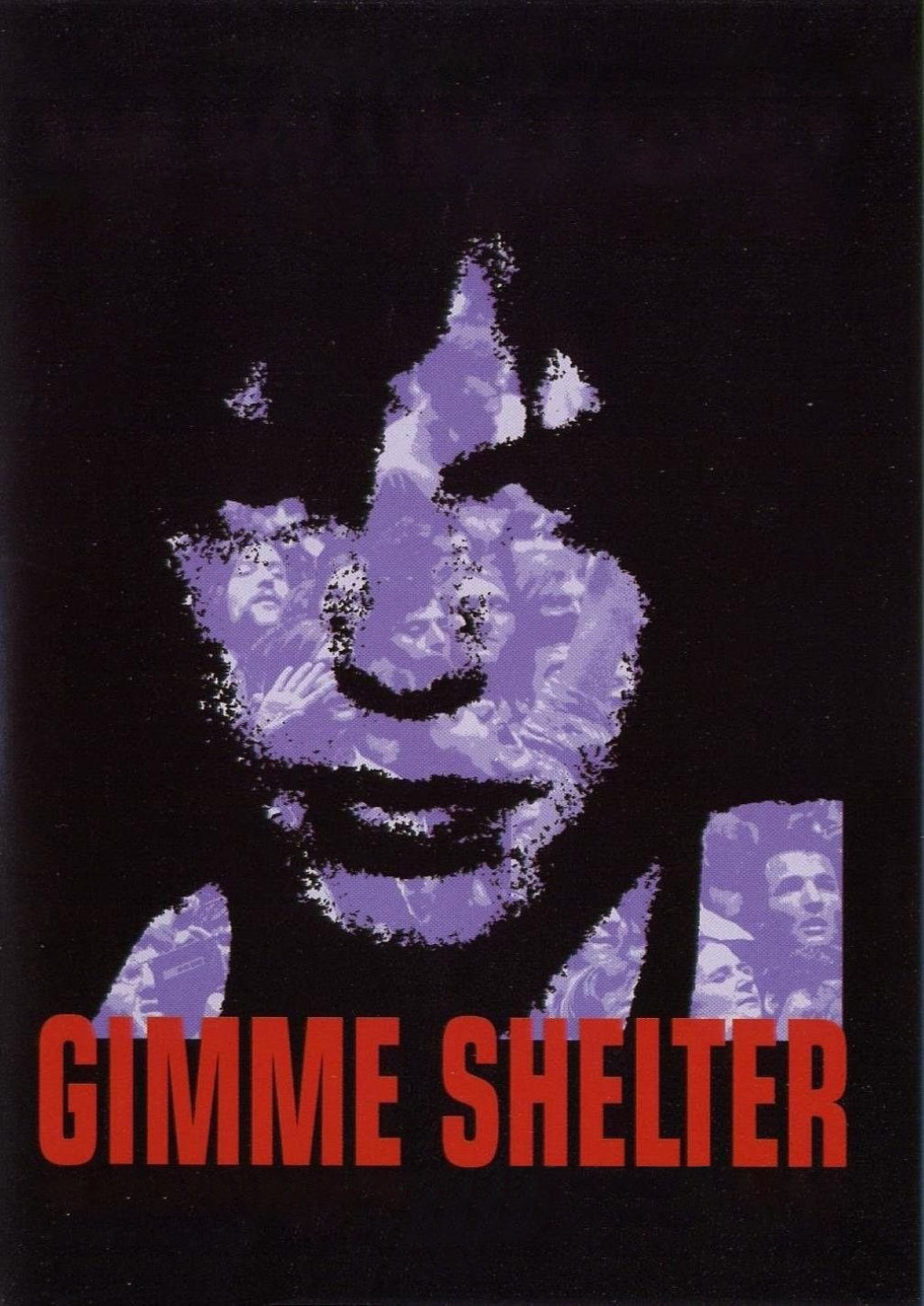

Just as Rugoff gambled on feature films that were way outside of the mainstream, he doubled down and began to acquire documentaries. Taking the genre out of the classroom and booking them into his theatres, he backed their releases with big marketing budgets. His wager paid off. Three of his releases, The Hellstrom Chronicle, Marjoe and Harlan County U.S.A. won Best Documentary Oscars. Other Cinema 5 docs include the iconic surfer film, Endless Summer; the Maysles brothers’ Gimme Shelter, chronicling the Rolling Stones’ ill-fated concert tour that was considered the end of the Woodstock nation; Pumping Iron, featuring an unknown Austrian bodybuilder named Arnold Schwarzenegger; and The Sorrow and the Pity, Marcel Ophuls’ film about the collaboration between the Vichy government and the Nazis, which Roger Ebert called “One of the greatest documentaries ever made”.

By 1976, his instincts fading, Rugoff seemed to have lost his magic touch. Some blame his second wife, Susie Childs, who employees called ‘the Yoko Ono of Cinema 5’. An outsider who seemed to come out of nowhere, the new Mrs. Rugoff was suddenly involved in every aspect of the business from selecting films to coming up with the recipe for the cookies that replaced traditional concessions at Cinema 5 theatres.

According to Deutchman, the real reason for Rugoff’s downfall was that he overpaid for The Man Who Fell to Earth starring David Bowie, which landed with a thud at the box office. Nonetheless, Rugoff continued to throw money at it. The film, says Deutchman, “was ultimately his biggest failure.” The beginning of the end, a string of unsuccessful films followed, unnerving, Cinema 5 stock holders. Unable to survive the bloodletting, Rugoff was fired in 1979.

The post-mortem on the showman’s downfall must acknowledge that the major Hollywood studios began taking cues from his playbook. Suddenly the art films that were making money were made in America by directors like Sidney Lumet, Robert Altman and Michael Cimino. Notes Deutchman, “At that point, it was a double whammy for Rugoff because his own movies were not doing well and he was booking them in his own theatres, which meant that he was missing out on a lot of successes that were going to other theatre chains.”

Perhaps his ill-tempered behavior came back to haunt him. Unable to find another job, took refuge in Martha’s Vineyard, where he tried and failed to recreate the magic by opening a theatre in an abandoned church. All but forgotten by the industry that he helped create, he died in 1989 at the age of 62.

As longtime film journalist, Harlan Jacobson says in Searching for Mr. Rugoff, “Usually when people in the entertainment business get kicked out of jobs, there’s typically a second or third act. Rugoff’s disappearance was unique in that regard because there was never a follow up. He literally disappeared.”

While Donald Rugoff may have vanished from people’s call logs and ultimately, from their memories, his legacy, as the father of the independent movement, lives on and is beautifully acknowledged in Ira Deutchman’s thoughtful documentary.