BRUCE DAVIDSON

Brooklyn Gang at The Cleveland Museum of Art

The American photographer Bruce Davidson is now 87, and his work behind the lens has spanned nearly six decades. His photographs are renowned for their depiction of individuals and communities that have been isolated or marginalized. In 1958, he joined the prestigious photography agency Magnum Photos after meeting Henri Cartier-Bresson, one of its founders. An outsider looking in, his success as a documentarian is his ability to remain in the shadows- as an observer, and never a participant. In a 2019 interview with The New Yorker, Davidson spoke about one of his first projects, Brooklyn Gang, “I think I was drawn to their life—their depression, their anger,” he said. “The first day I was there, the gang leader said, “There’s a great view on this roof. I’ll take you up. I said to myself, “If I go with him, he’s gonna toss me off.” It happened in “West Side Story,” why wouldn’t it happen to me? I knew if I didn’t go, they wouldn’t respect me. So I went. It actually was good views.”

Davidson’s series Brooklyn Gang is now on view at The Cleveland Museum of Art. Barbara Tannenbaum, Chair of Prints, the Drawings, and Photographs and Curator of Photography at the museum, took time to discuss Davidson’s exhibition.

RD: Can you explain the significance of Bruce Davidson’s Brooklyn Gang series?

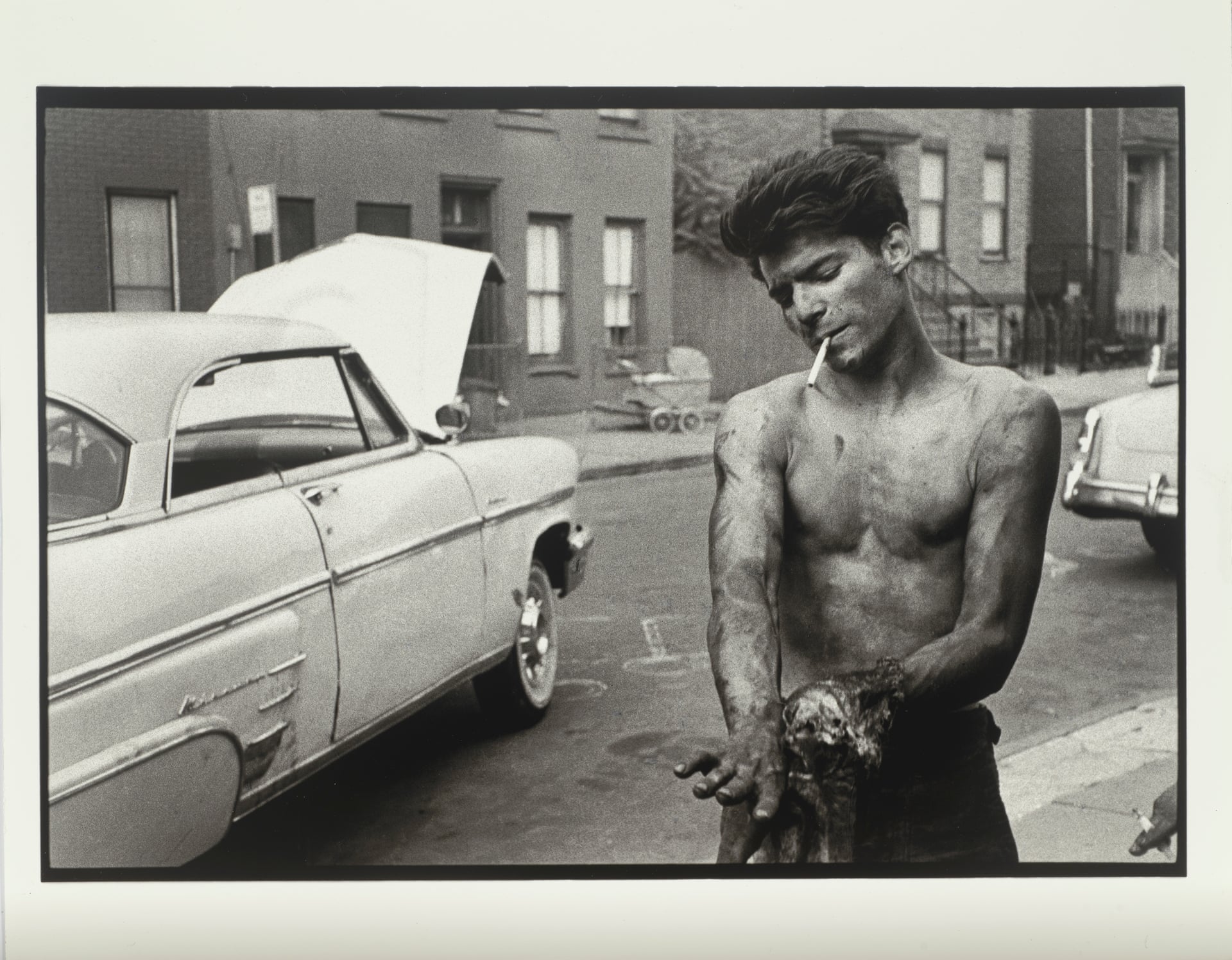

BT: Bruce Davidson’s Brooklyn Gang chronicles life in summer 1959 for the Jokers, a group of Irish and Polish youths who were but one of many violent teenage gangs worrying New York City officials in the 1950s. Gangs were a hot topic in the 1950s, a phenomenon avidly analyzed by sociologists and the press. They even inspired a musical—”West Side Story,” which opened on Broadway in 1957. In that era, gangs were regarded either as evidence of societal deterioration resulting from poverty or as the most visible manifestations of a socially disengaged generation of males—rebels without a cause. While the societal model of the time was the man in the gray flannel suit delighted to have a steady 9-to-5 white-collar job and a house in the suburbs, many people felt alienated from that ideal, which would very soon give way in the rebellious 1960s. Brooklyn Gang allowed Davidson to deeply explore a counter-culture at a moment of impending societal change; doing so led him to uncover his own feelings of failure, frustration, and rage.

RD: Why was Davidson drawn to this specific neighborhood/gang in NYC?

BT: Davidson read a newspaper article about a gang that had suffered some serious injuries in a “rumble”—a fight with an opposing gang—and decided to meet them. The city had assigned most gangs, a social worker or counselor, so Davidson arranged through him to meet the gang. He must have found them an interesting enough group of people to invest time in.

RD: As an outsider, how could he gain their trust to document his observations?

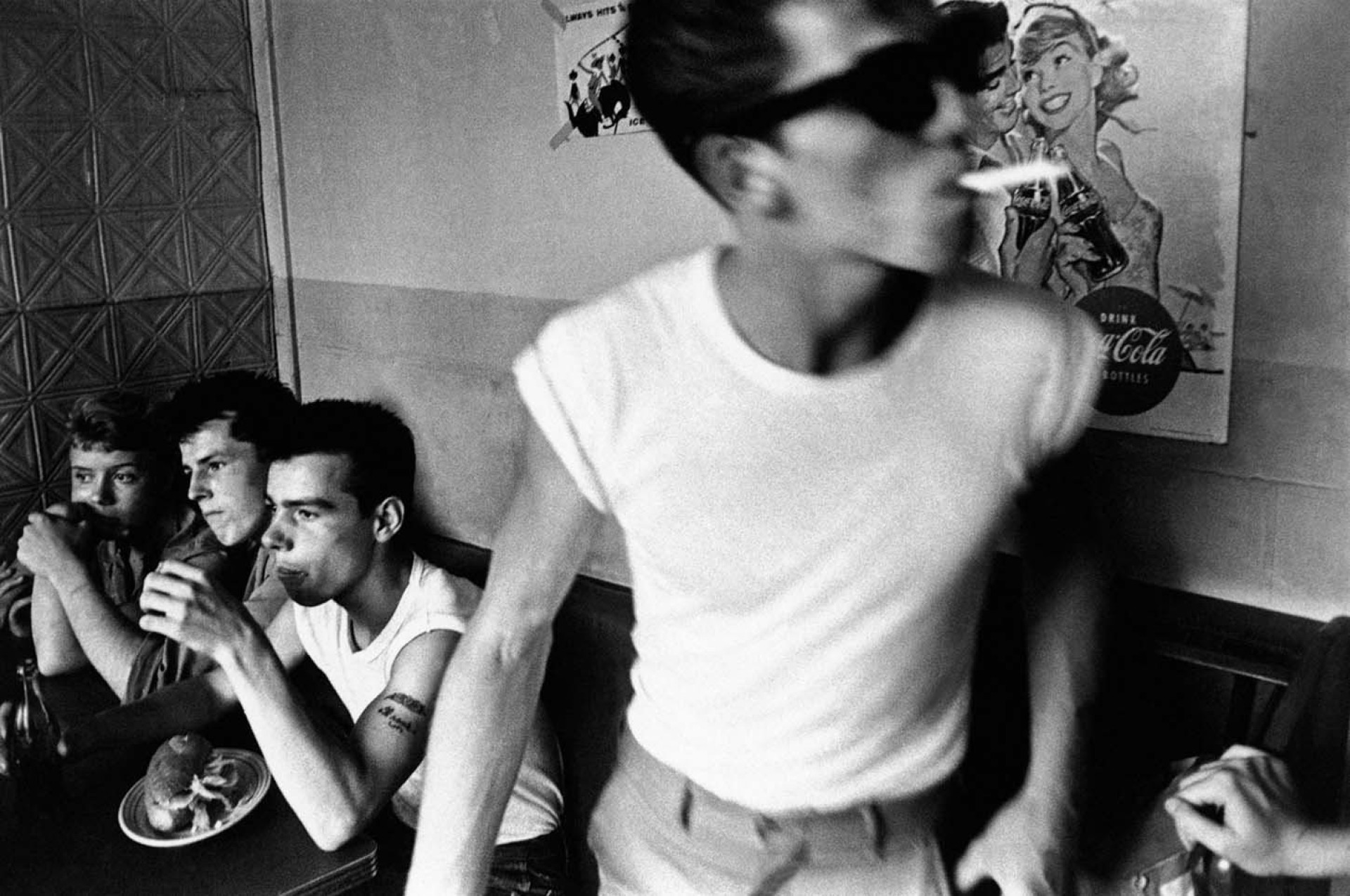

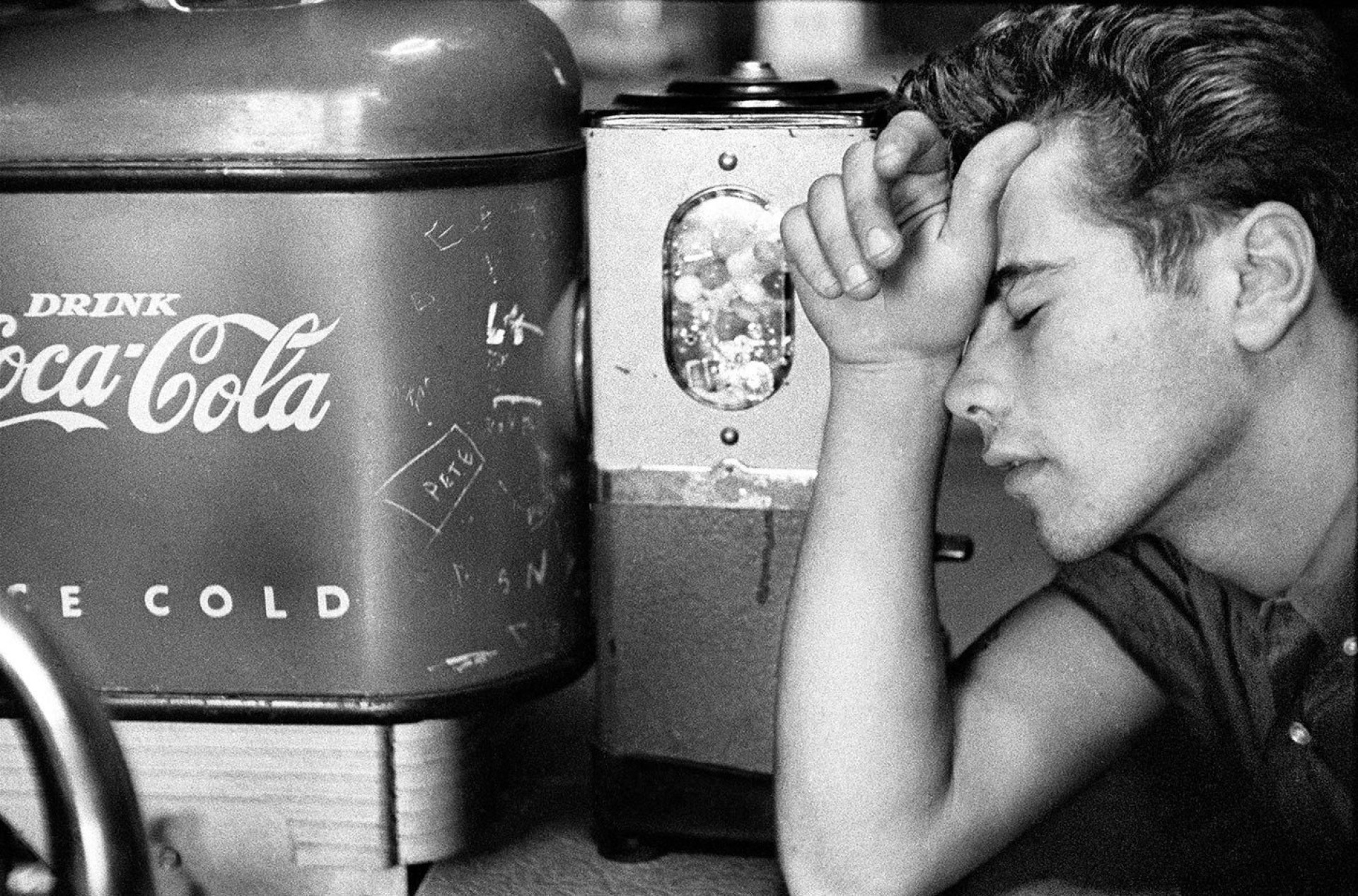

BT: At first, the gang members did not trust Davidson. It took a while for them to relax around his camera. In his favor, he was close enough in age, not to be a parental figure. Davidson was 26, while the gang members were mostly 15 or 16. Like the gang members, Davidson flouted certain mainstream values. He was a freelance photographer who could come and spend the day hanging out with them, not someone with a 9-to-5 job. And he invested several months hanging out with them on street corners and in the local candy store, and going with them and their girlfriends to the beach at Coney Island. He was around them often enough, and long enough that they stopped posing for his camera and forgot about it. Describing his process, Davidson says, “I stay a long time. . . . I am an outsider on the inside.”

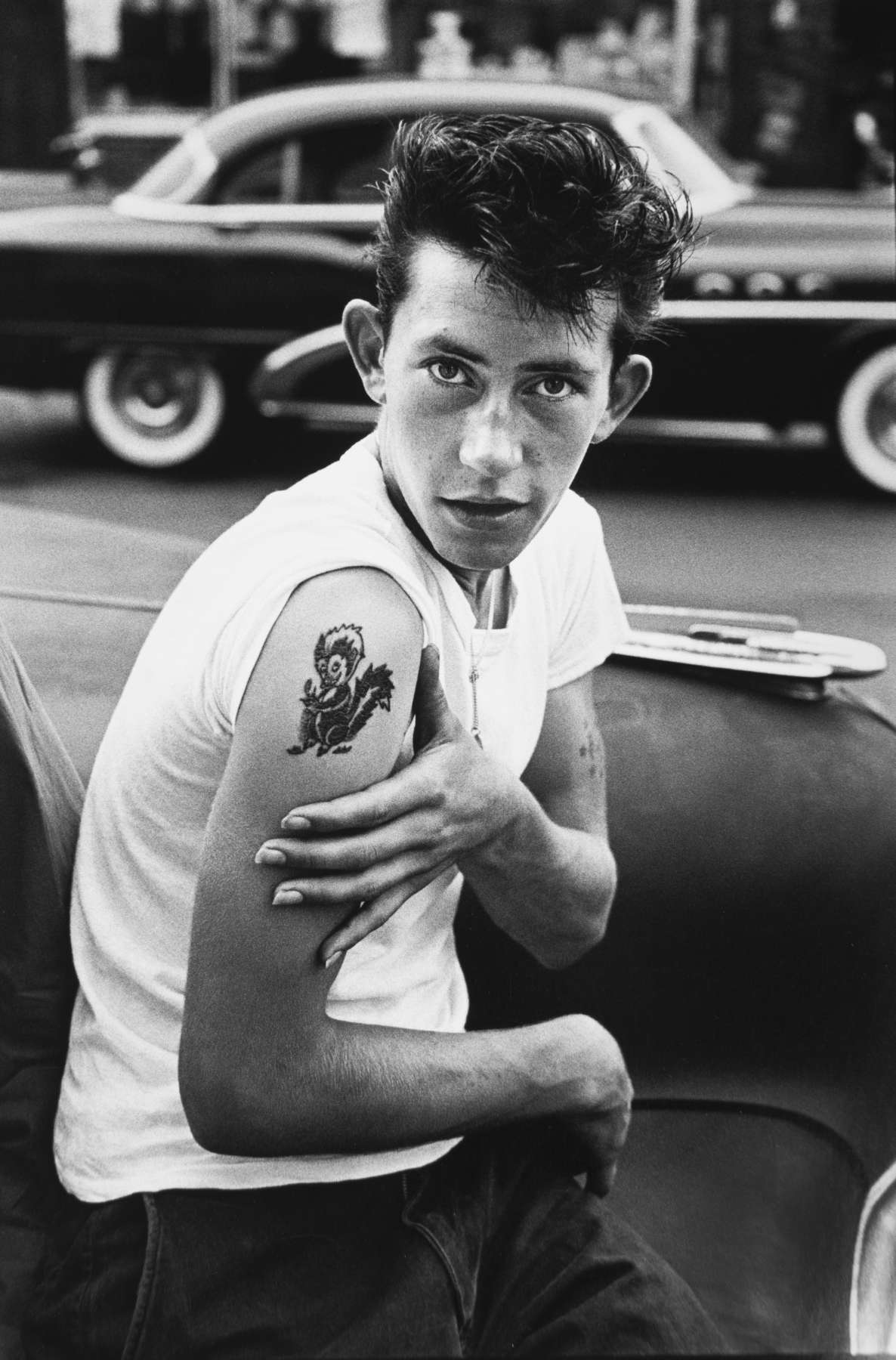

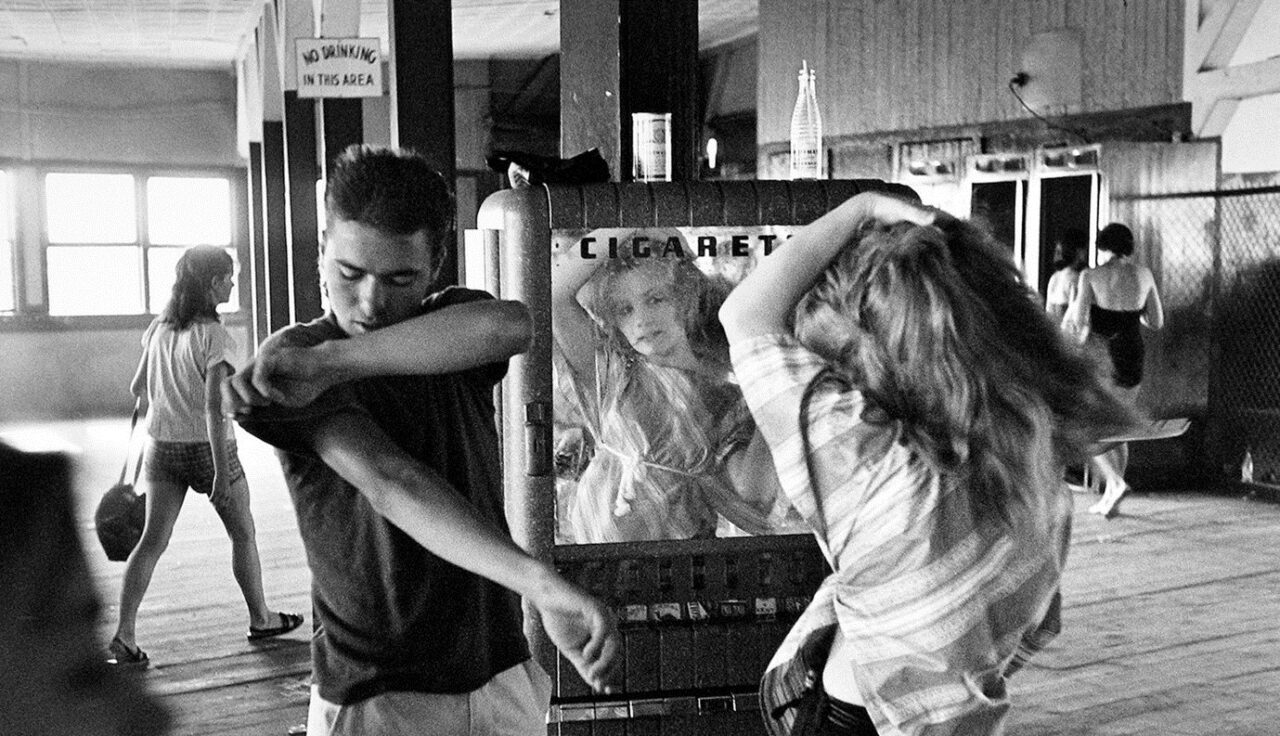

RD: Can you tell me about the photo of the couple in front of the mirror of the cigarette machine?

BT: The best-known image in the series, taken in front of a cigarette machine at Coney Island, shows Artie Giammarino, who later became a transit police detective. Cathy O’Neal, whom the boys considered “beautiful like Brigitte Bardot,” is seen here at thirteen or fourteen, around the time she began dating the “coolest” of the gang, Junior Rice. At fourteen, she got pregnant. Though they were both under the legal age, they married but later divorced. Junior became a heroin dealer and user; within a few years, drugs would claim the lives of many in the gang and in the neighborhood. Years after their divorce, Cathy committed suicide by shotgun. Yet we see little hint of that dark future in Davidson’s photograph, which emphasizes Artie and Cathy’s youth and beauty and the pleasure of the moment. To our eyes, accustomed to associating gangs with drug use and gun violence, these images conjure a more innocent era than our own. Viewers in 1959 would have regarded the youngsters’ hairstyles and tattoos, not to mention their underage drinking, smoking, and sex, as ruinously delinquent behavior. Davidson was careful not to pass judgment in his photographs.

RD: Are there any other photos in the exhibit that you would like to mention?

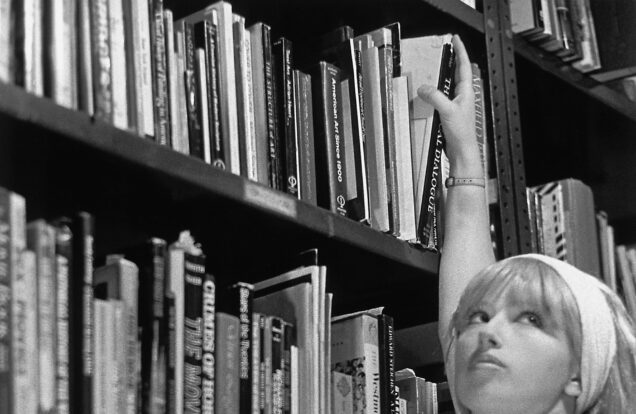

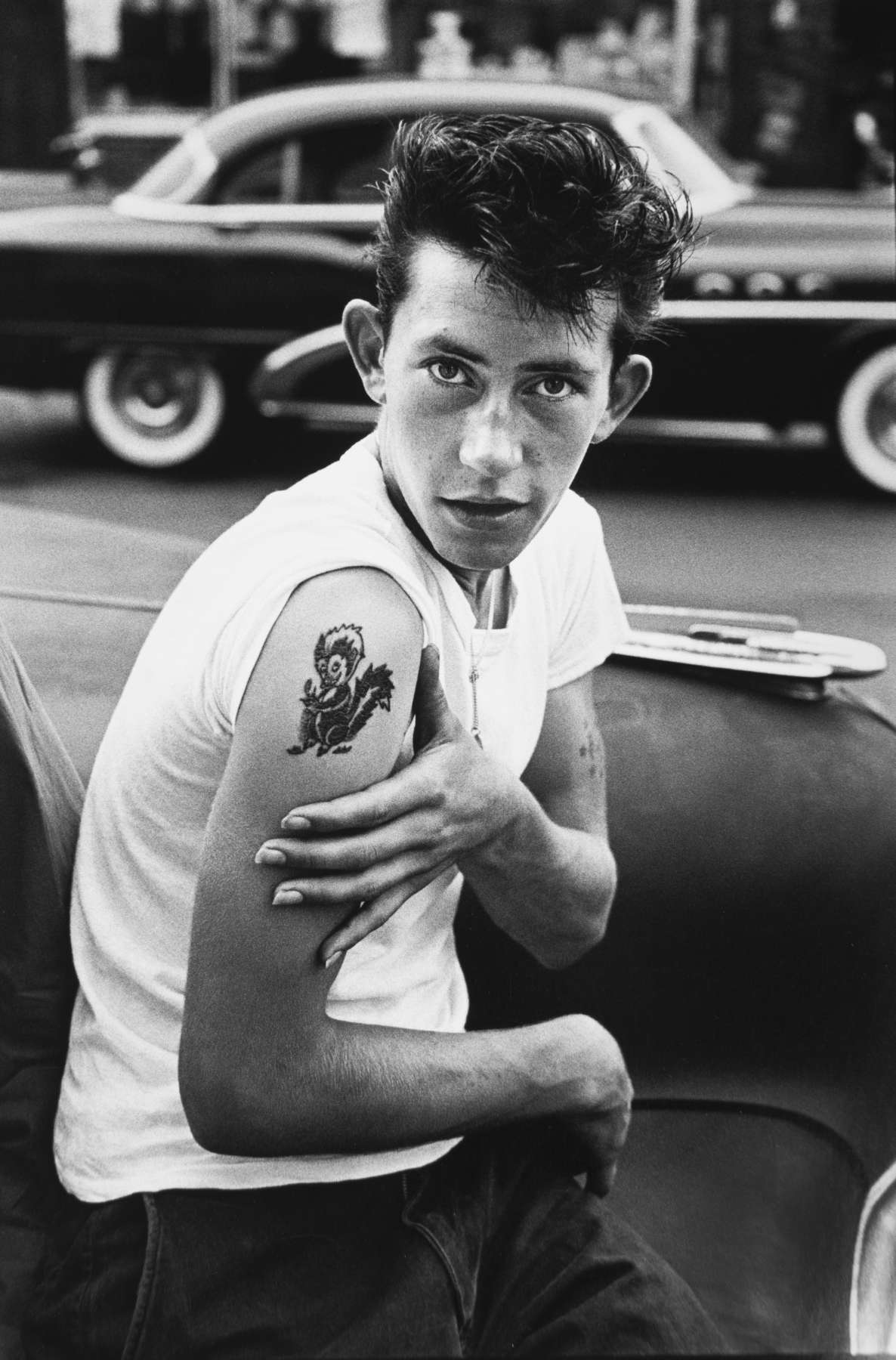

BT: A number of the pictures depict the teenagers exploring lust and love. This image shows a group driving home from Coney Island. The male in the back seat is Lefty, identifiable by his tattoo. “We always wondered why the girls liked him,” pondered Jokers member Bob Powers. “We never thought he was good-looking, but all the girls loved him. It was amazing.” The exhibition includes four images of this couple making out, taken in succession, that have never been published as a group, despite their cinematic quality when seen together. The one seen here became an iconic image and, in 2009, was the cover for a Bob Dylan album, Together Through Life. A half-century after it was taken, it was the album cover and separated from its sociological context. Davidson’s image has lost its connotations of delinquency and danger. Instead, it conveys a seductive mood and seems to harken back to a more innocent era. Looking back at the series in 1998, Davidson said that he felt “the reason that body of work has survived is that it’s about emotion. That kind of mood and tension and sexual vitality, that’s what those pictures were really about.”

RD: What do you hope viewers gain/learn from this exhibition?

BT: This exhibition examines the Brooklyn Gang photographs through multiple filters. In 1960 writer Norman Mailer met the gang and penned an essay to accompany Davidson’s photographs in Esquire magazine, which is included in the exhibition. In 1998 the photographs were published as a book with accounts by Davidson and Jokers’ member Bob Powers, who wrote a more detailed memoir in 2012. The wall texts that accompany individual works include insights into the gang members’ feelings, and fates garnered from those later sources benefit from hindsight. A final filter is that of societal change over time. These images conjure a more innocent era to our eyes, accustomed to associating gangs with drug use and gun violence. I hope that viewers become aware that how we interpret a photograph depends on our perspective and that the present informs our view of the past.

Bruce Davidson: Brooklyn Gang at The Cleveland Museum of Art on view through February 28, 2021.