Robert Mapplethorpe

Controversy & Power Will Grip the Guggenheim

In 1989, the director of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D. C. cancelled a Robert Mapplethorpe exhibition weeks before it opened, sparking an inferno of protests; the show later moved to the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, where the establishment and its director faced obscenity charges. Mapplethorpe and controversy fit together like two beautifully groomed men, and historically this was due to the sexual nature of Mapplethorpe’s work. At the upcoming show at the Guggenheim, however – which opens in January 2019 – something feels different.

This time, it’s not the proverbial “them” – The Man, the government, the dicks looking to screw over cultural envelope pushers – it’s us, and we didn’t see this coming.

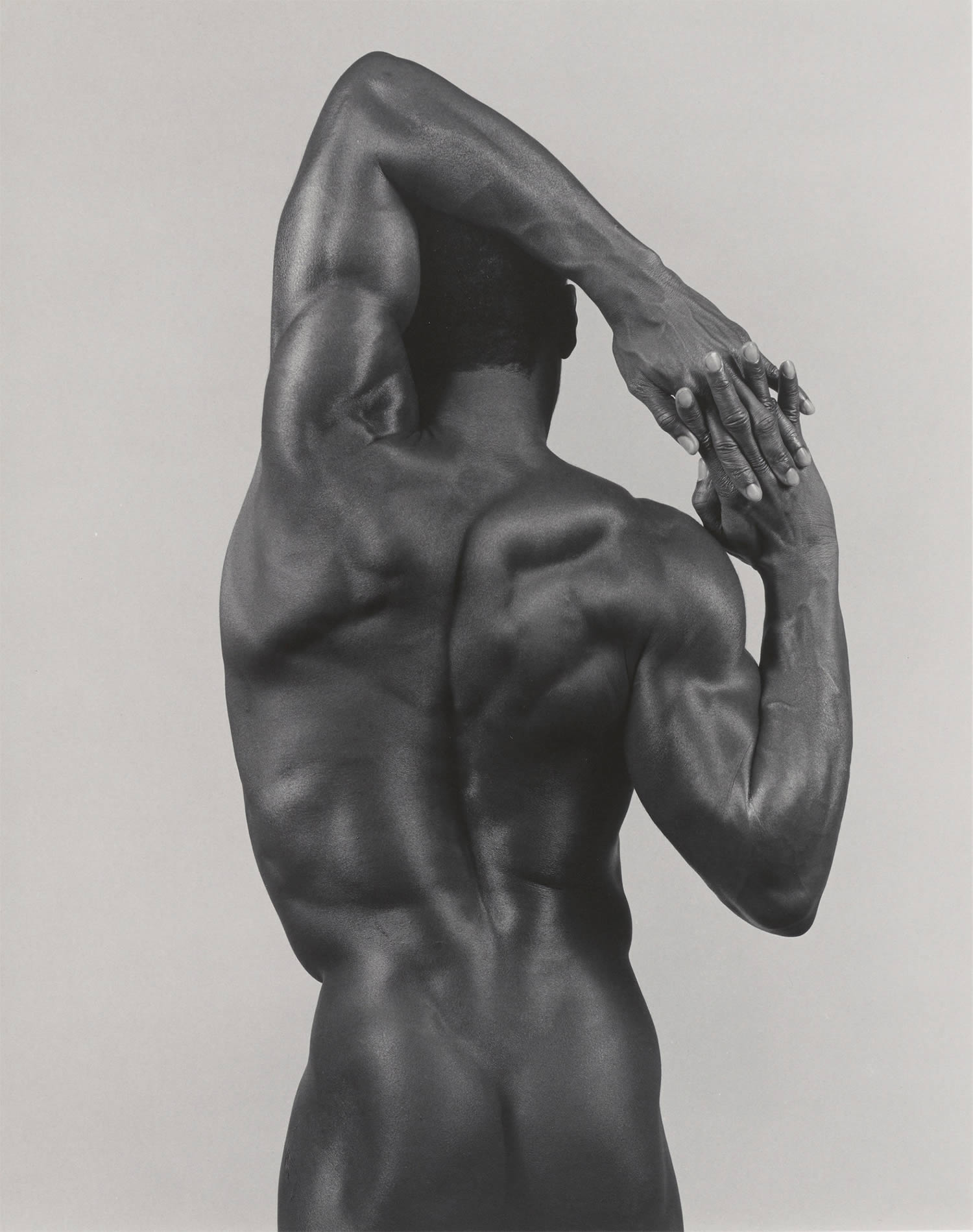

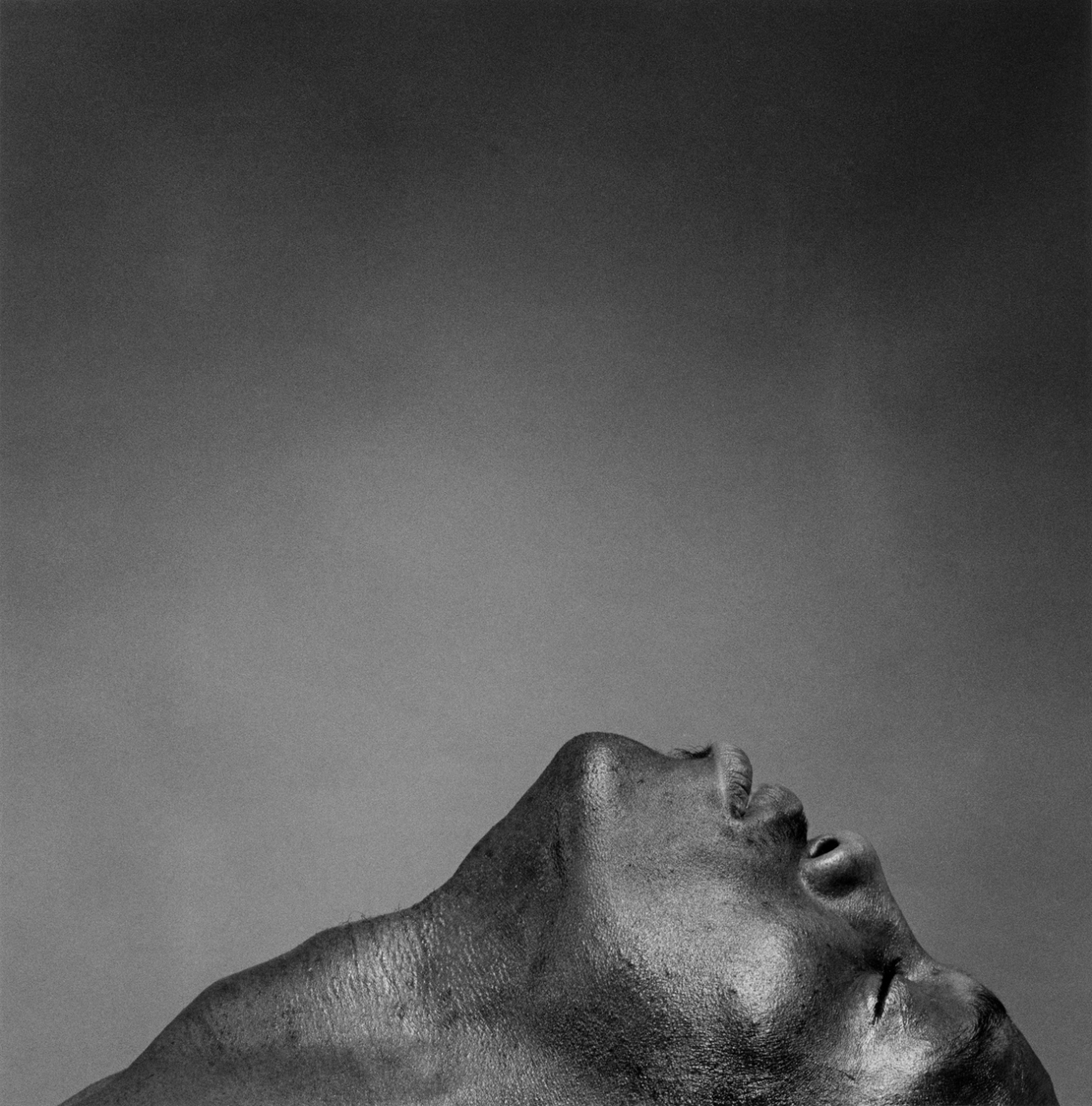

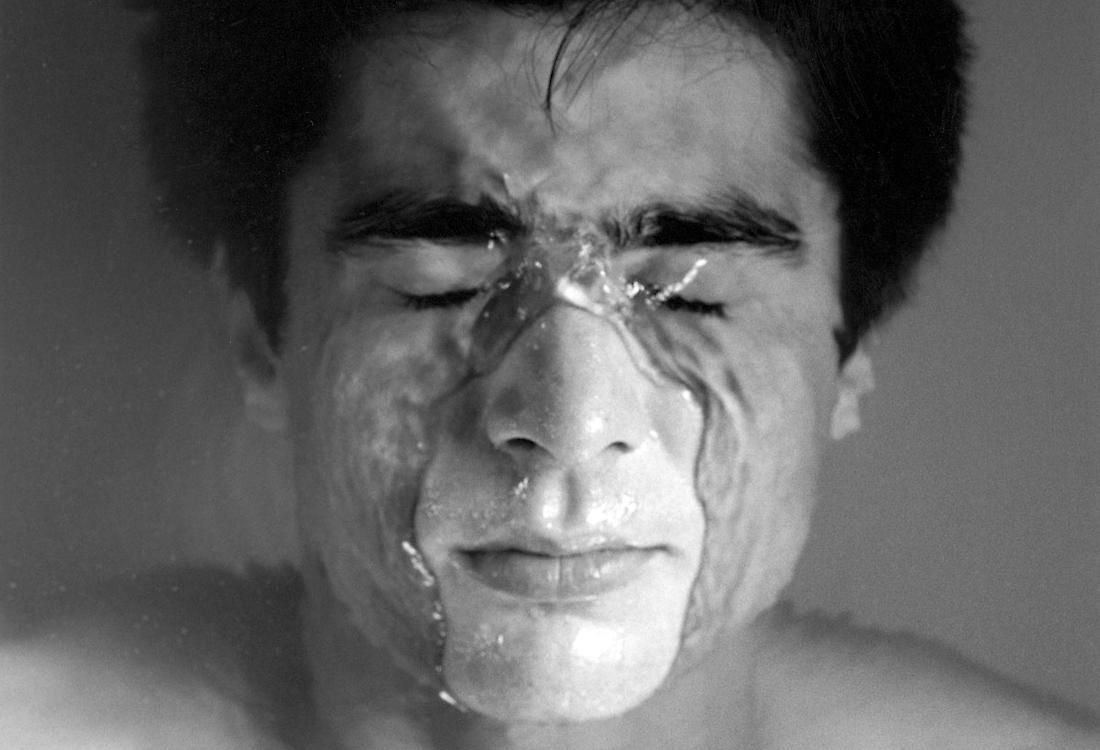

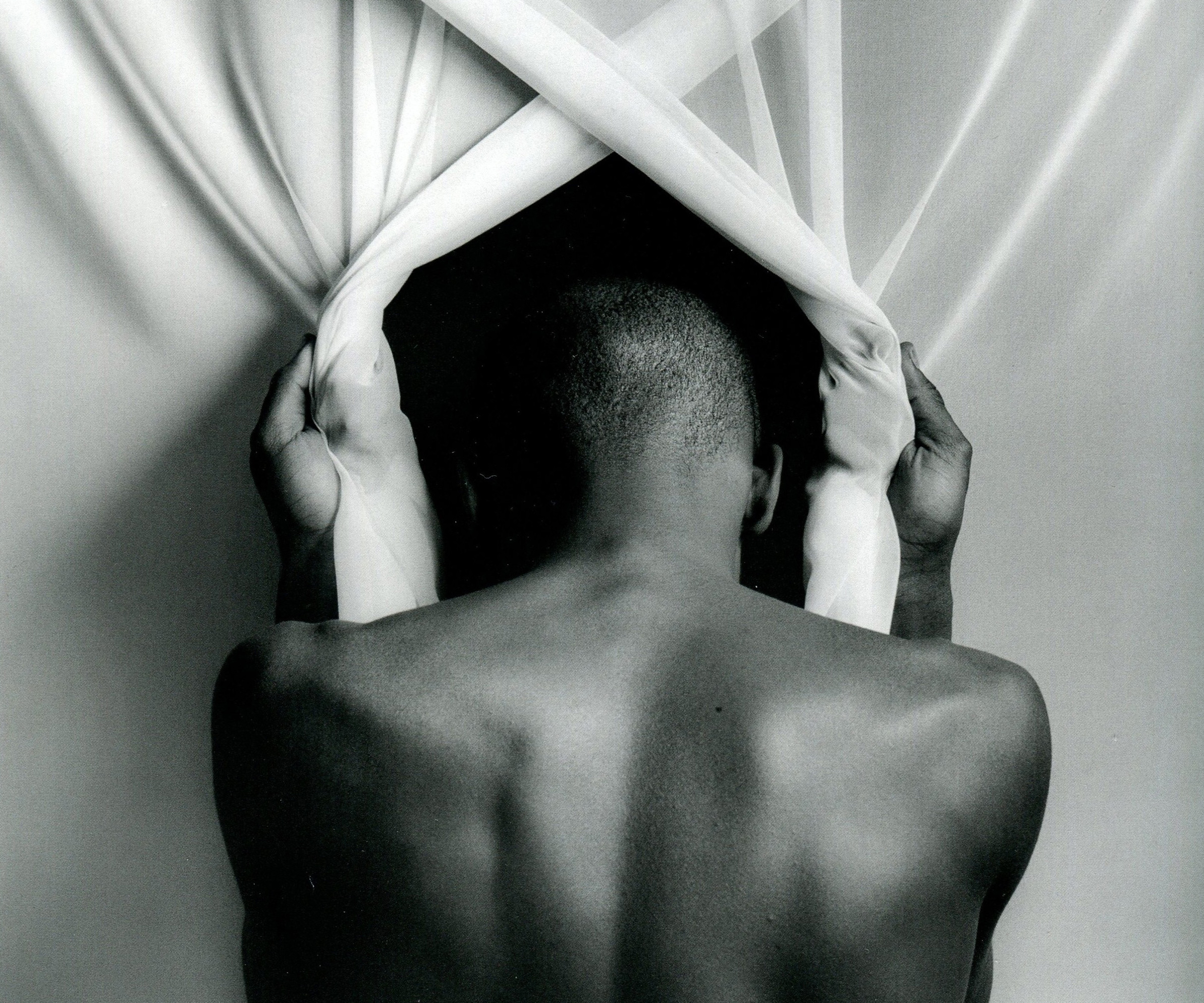

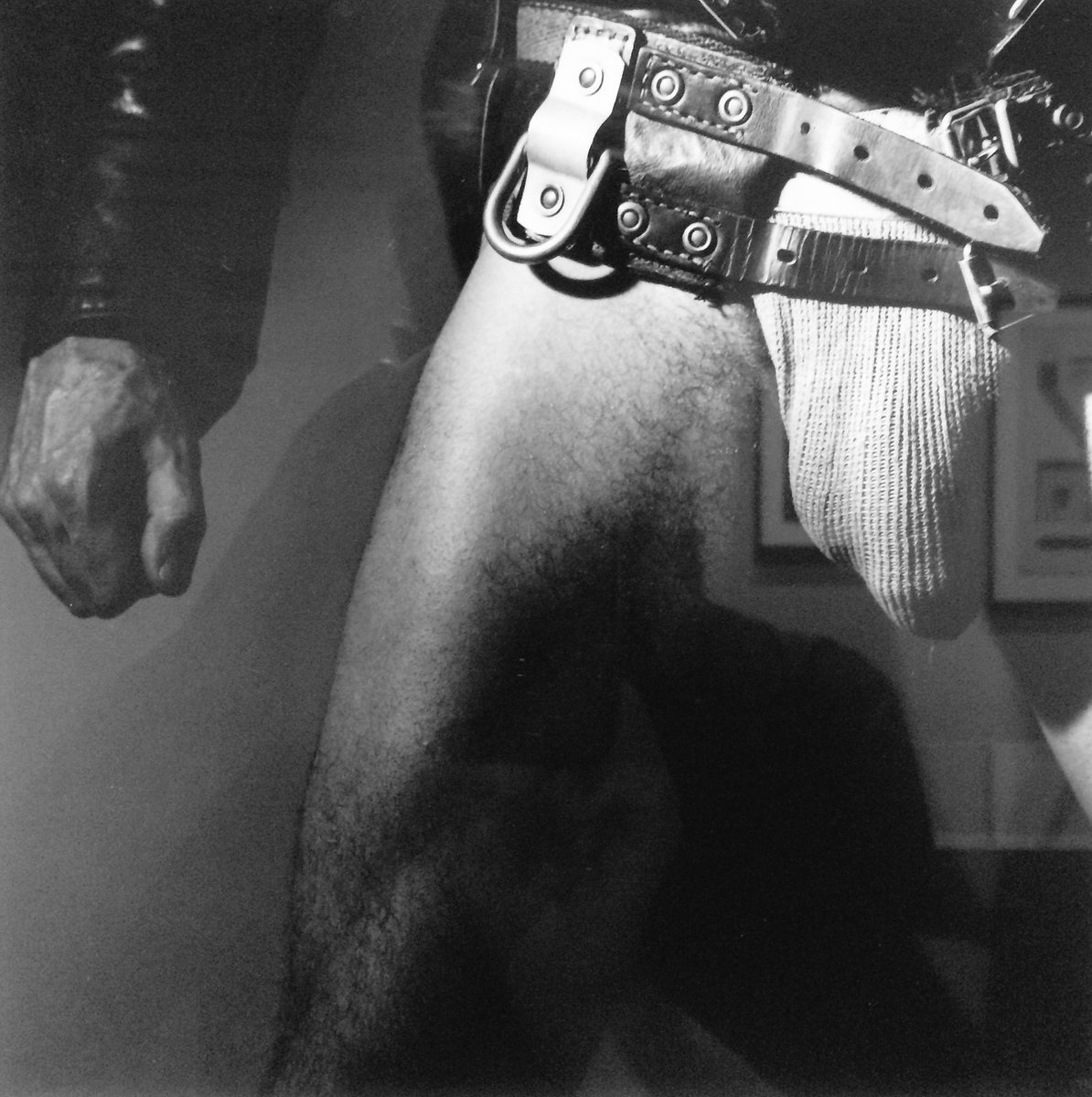

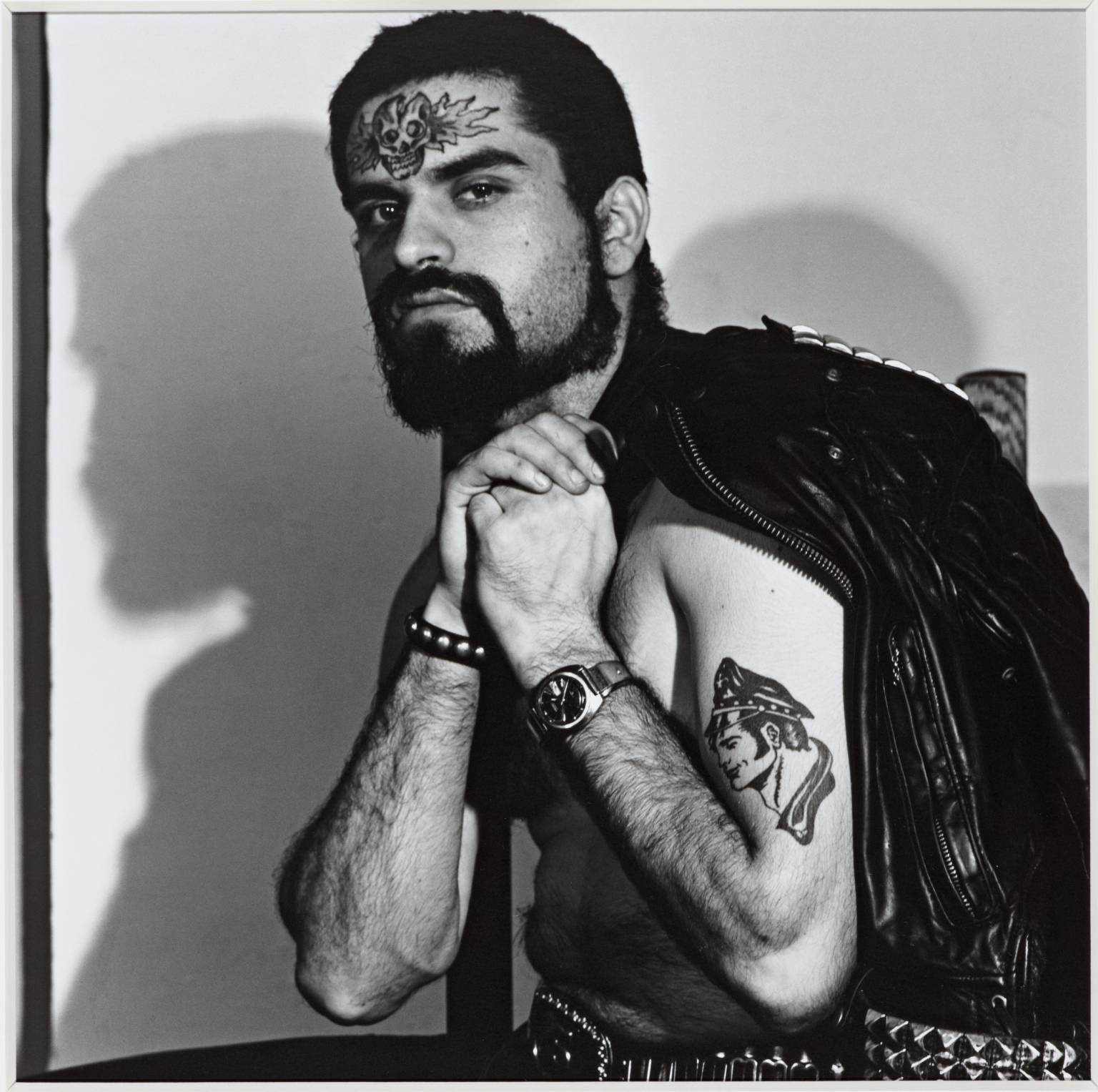

To see his work now, through the contemporary lens of anything-goes-and-it’s-all-been-done, it seems more radical to behold skin that hasn’t been airbrushed, portraits that haven’t been facetuned, and contours that haven’t been perfected by the patron saints of PhotoShop than to see people in an erotic state. The prevalence of needles among beautiful people hasn’t changed much since the 1980s – it’s just that now they deliver filler and Botox more often than they deliver heroin.

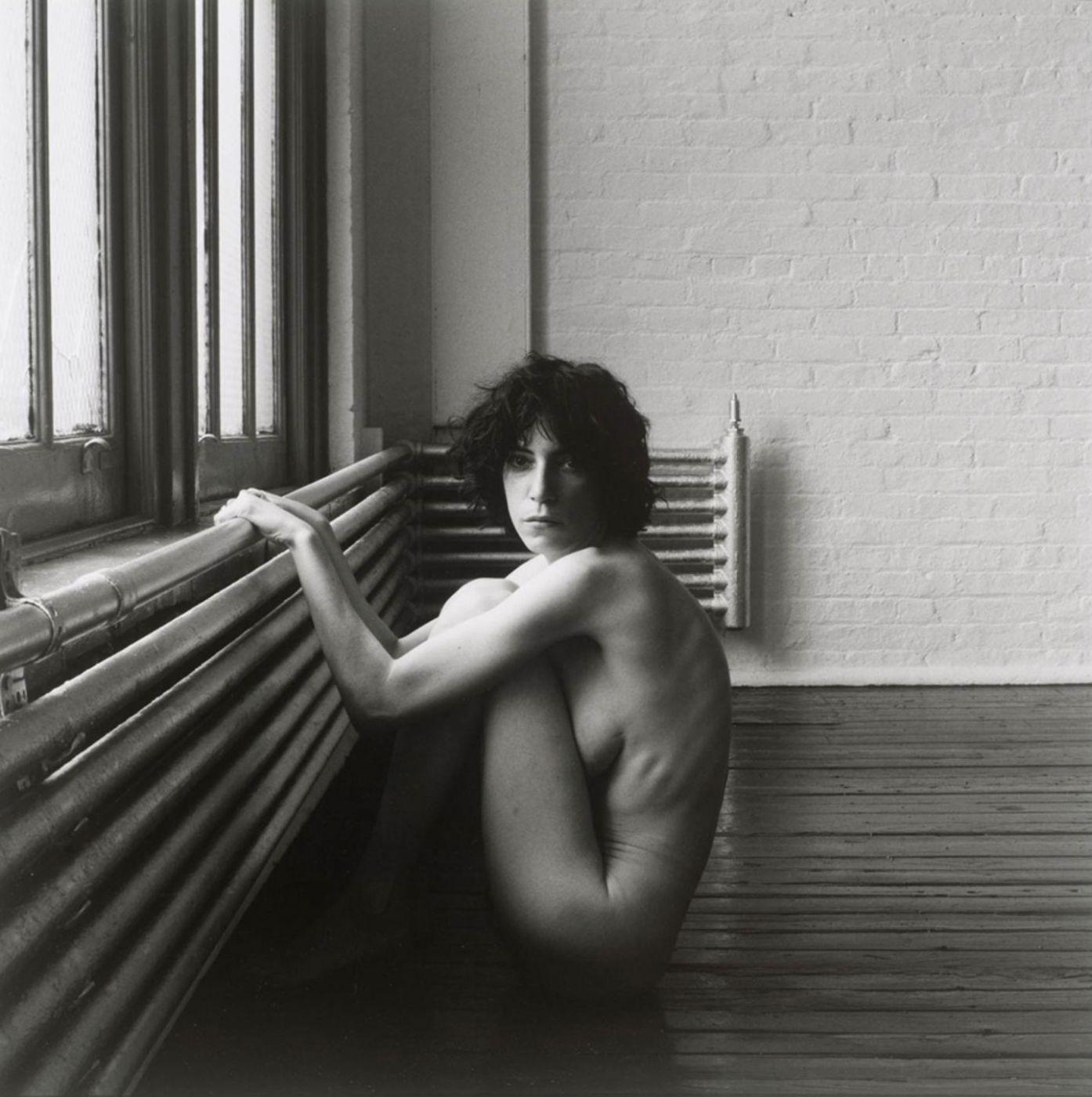

Maybe we’ve just looked at too many nudes, but to gaze upon Mapplethorpe’s work with fresh eyes, it’s not the subject matter that jarrs us. It’s that we haven’t seen real, honest-to-bush texture in a long time.

Arts magazines, culture gurus and politicians alike have all spilled millions of words about the vulgarity and tenacity of Mapplethorpe’s work; they call him tasteless as often as they call him a creative god. He was the angel-lipped beatnik who stole Patti Smith’s heart in the steam of a New York summer. He took the stigma out of ass play and turned it into the kind of art that makes collectors cream themselves at auctions. That hasn’t changed, and it’s impossible to do justice to his work without addressing its social effects.

All of this speaks clearly of his power as an artist.

But if we’re so mesmerized by the presence of texture that the kinky curves of pistils and stamens aren’t the first details we notice, what does that say about us?