ZANELE MUHOLI STUNS

Magnificent Photographs of Beautiful Lives

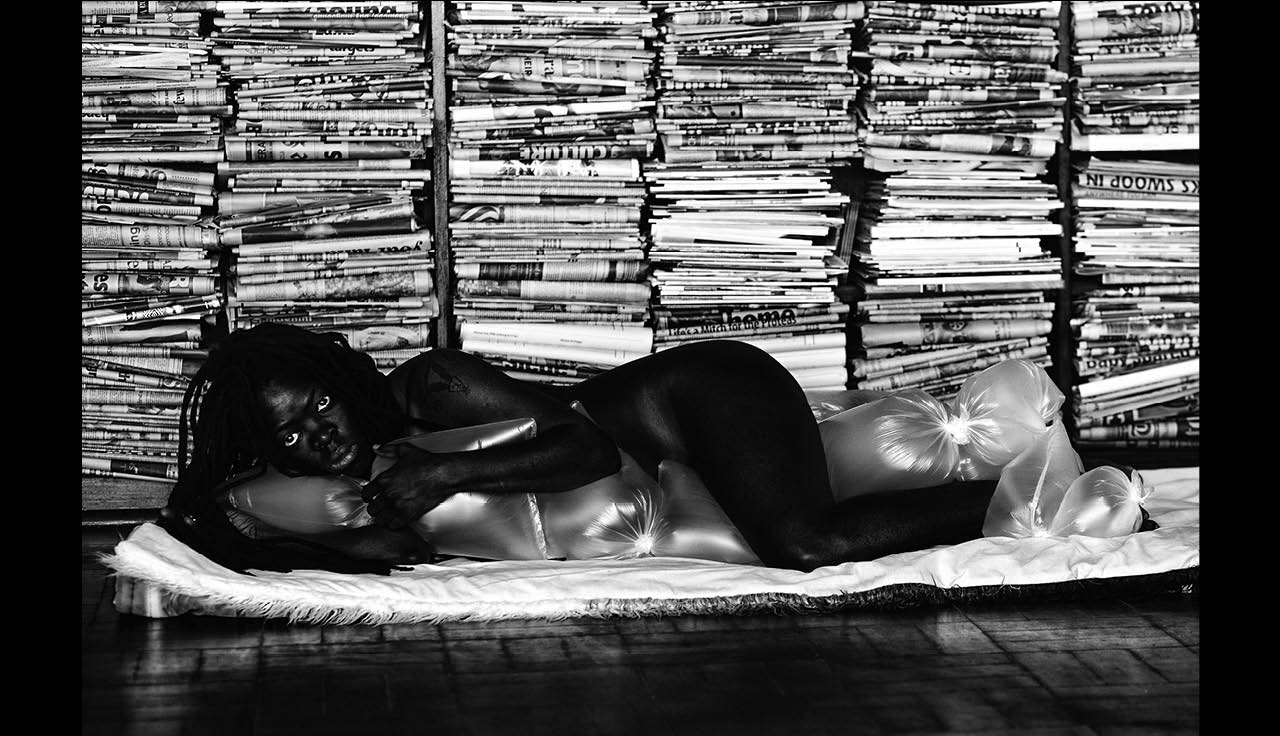

After experiencing pandemic delays and setbacks, the Tate Modern is at last set to host South African visual activist Zanele Muholi in a major survey. Spanning many years, the exhibition is a culmination of various bodies of work narrowed down to approximately 260 images. Ranging from Muholi’s first notable works in the early 2000s to their most recent creations in masterful self portraiture, the broad oeuvre is brought to center stage. The work is both historical documentation and a form of storytelling. Confrontational, gripping, and raw, Muholi outlines the form of a previously unseen South African people.

Grounded in activism at its core, the work of Muholi crosses the borders of conventional art. As a Black and queer South African, Muholi grew up during the peak of apartheid, which spanned up until the 1990s. In the wake of social upheaval, South Africa has been attempting to upright itself since then. Like so many other socio-political ecosystems, there is a long way yet to go. In South Africa and all corners of the world, Black and LGBTQIA+ communities continually face discrimination, prejudice, and violence.

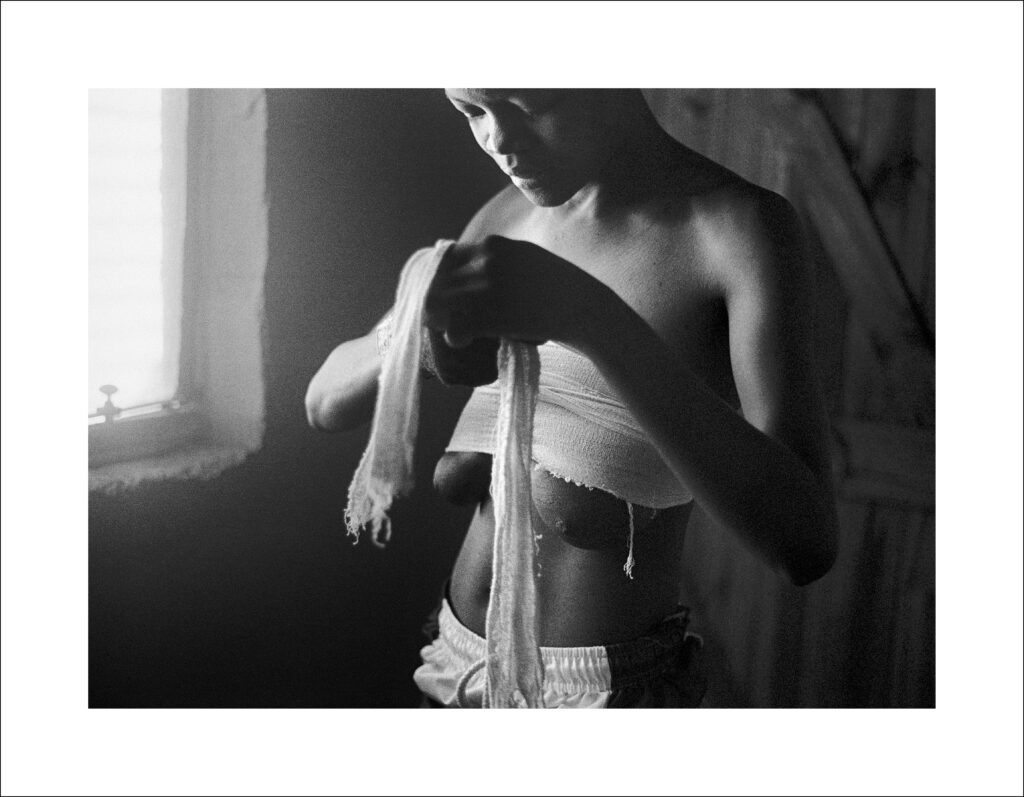

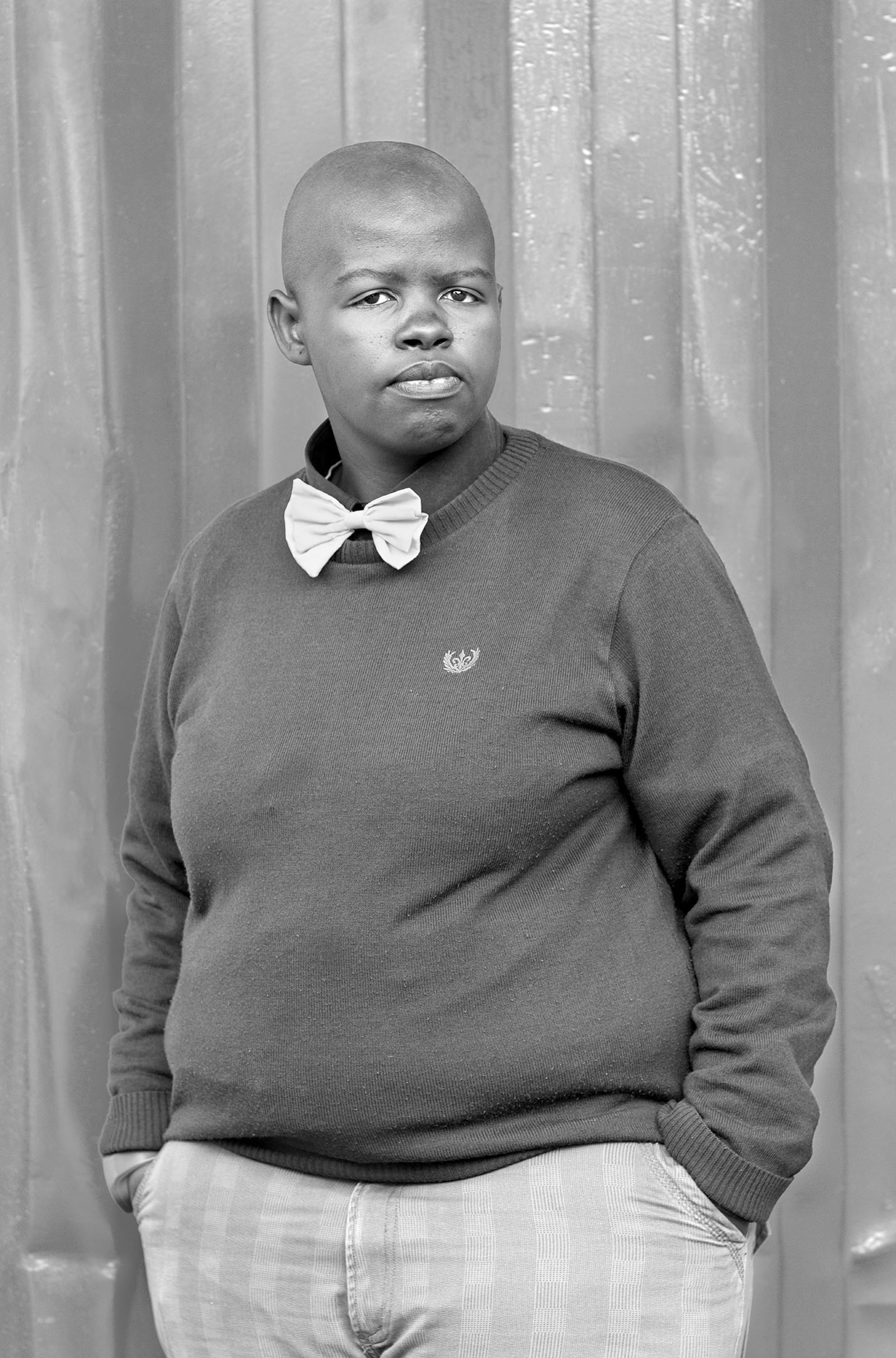

Muholi’s work sheds light upon a group of people marginalized and underrepresented in the world of photographic documentation. A previously untapped vein in photography, the LGBTQIA+ culture in South Africa is at last depicted in the striking images of Muholi’s creation. The narrative of a beaten-down community is brought to life, and history itself is written and circulated in a reverberating collection of portraits.

An ode to painful experiences and the strength of the human condition to overcome it all, the art is for everybody. It is for those within the sphere of the LGBTQIA+ community who recognize and find identity within aspects of the experience, as well as those outside of the sphere who are given the opportunity to stand in solidarity in quiet moments of learning.

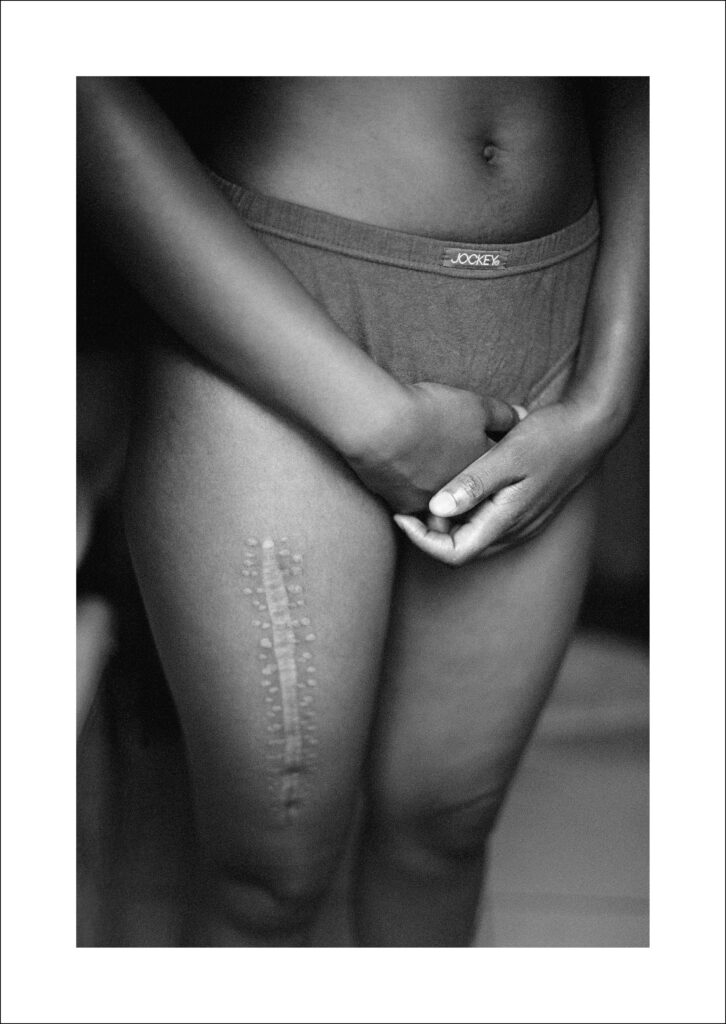

There is trauma and pain, as well as the celebratory continuation of survival. Survivors of abuse and hate crimes are pictured within Muholi’s images, wielding their scars and displaying the traits that set them apart.

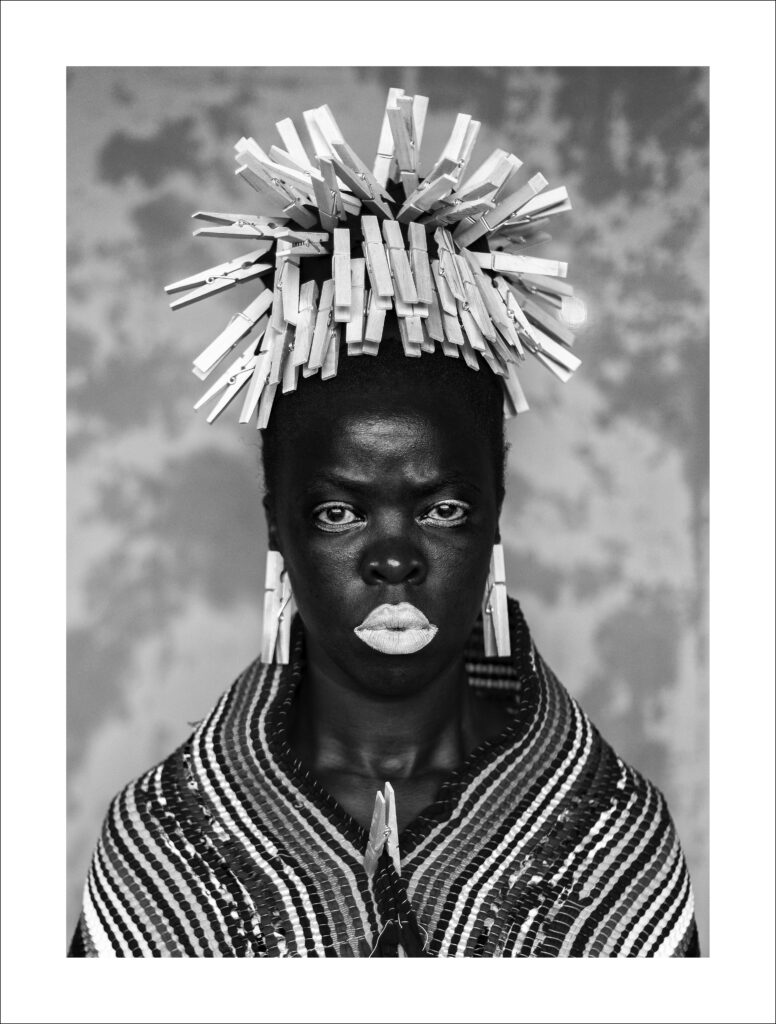

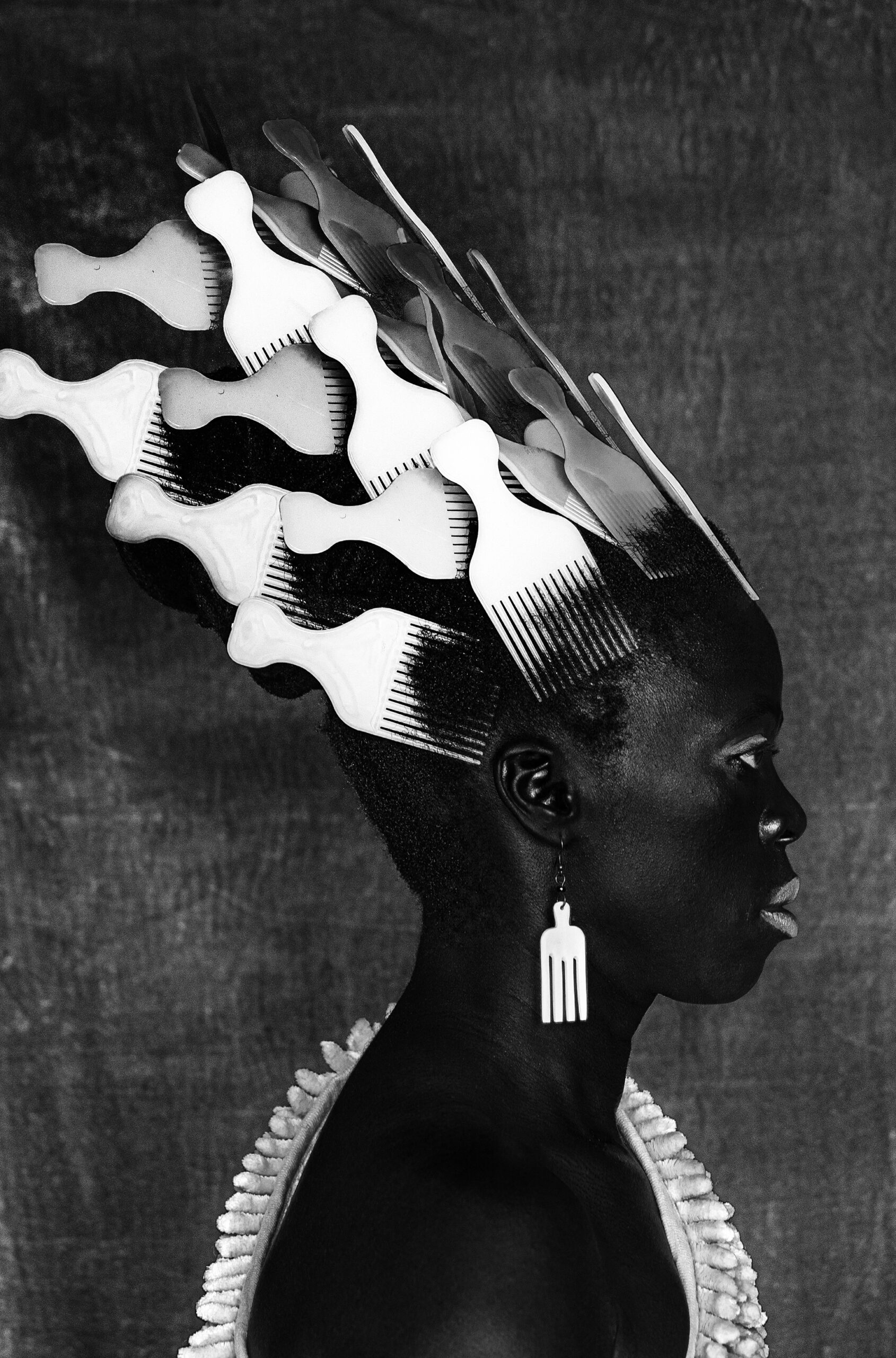

Notably, Muholi appears within the frames of their most recent work on self portraits, entitled Somnyama Ngonyama — Zulu for “Hail the Dark Lioness.” In an interview with the British Journal of Photography, the artist commented, “To face the camera is to open a conversation, to make yourself both vulnerable and powerful at once.” The strong contrasts of black against white are undeniably commanding and political. Muholi presents images of a people pressed down by their oppressors, but who defiantly and steadily stare down the barrel of a camera in their resilience.