Why We Love Westworld

A rundown of our favorite new show

Summer might be over, but a new mind-bending, bank-breaking show from HBO is, at long last, in full bloom. Following a string of catastrophes and setbacks with big-budget busts, such as Vinyl—cancelled due to poor ratings—and Lewis and Clark, an epic miniseries that, after millions of dollars and hours of footage in the can, was scrapped and restarted from scratch, the successful launch of Westworld, an ambitious sci-fi western, couldn’t have come at a better time. While its premiere, much like that of Game of Thrones, the flagship show that Westworld hopes to replace, was bogged down by the immensity of its premise, once the expansive world and rich plot is given ample time and space to unfold, we’re positive HBO will have a winner on its hands.

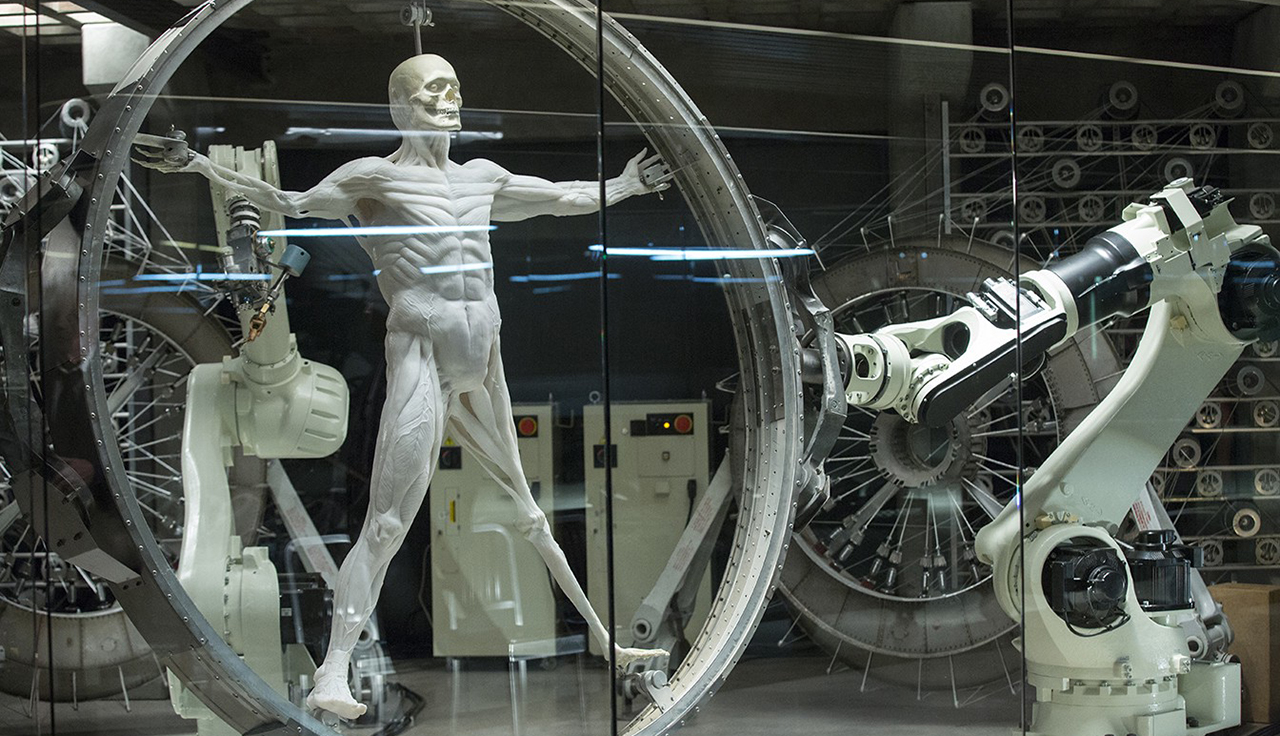

Based on a 1973 film of the same name, J.J Abrams’s reboot straddles two worlds: an Old West frontier town filled with robotic “hosts” to welcome paying visitors, and the sleek and sterile lab responsible for its creation. Delores (Evan Rachel Wood), one of the oh-too-real looking “hosts,” is our way into this labyrinth. Stripped from her home, a Truman Show–like West, where she exists solely for the pleasure of bona fide humans looking to get in on some good old-fashioned whoring, drinking and murdering, Delores is questioned by her creators—she’s programmed to think the conversation is a dream—who are trying to decide if she’s developing the sort of self-awareness that every cinematic A.I. scientist dreads. And that’s the basic question of the show: are these man-made creations, robots programmed for human benefit, becoming, well, human?

This question gives way to more provocative probings. Unlike most stories with an A.I. theme, we aren’t dreading the moment the “hosts” join us in the self-awareness party—we’re already right there with them. Because in this story, where humans are playing God, we can’t help but pull for their synthetic creations, whose predetermined and preprogrammed lives, much like ours, are out of their control and beyond their understanding. A meditation on both consciousness and free will, Westworld channels a little bit of Schopenhauer and Plato’s Cave. But where those philosophers employ shadows and empirical arguments, Westworld uses beautiful vistas, vixens and cowboys (James Marsden, anybody?), and a whole lot of skin and bloodshed (compliments of a sociopathic Ed Harris) to stir our minds and our desires in equal measure.