A Streetwalker’s Memoir

Blue Money Exposes Times Square’s Underbelly

On the heels of HBO’s 1970’s Times Square saga, The Deuce, comes the story of a young prostitute during those crazy, dirty, sleazy, pre-AIDs days in New York City. Writer Janet Capron’s mostly true memoir, Blue Money, exposes “the life” in a bold, comedic voice: the johns, her drug-fueled nights—speed was her high of choice—walking the dangerous streets, performing in live sex shows in Times Square. She doesn’t miss a trick.

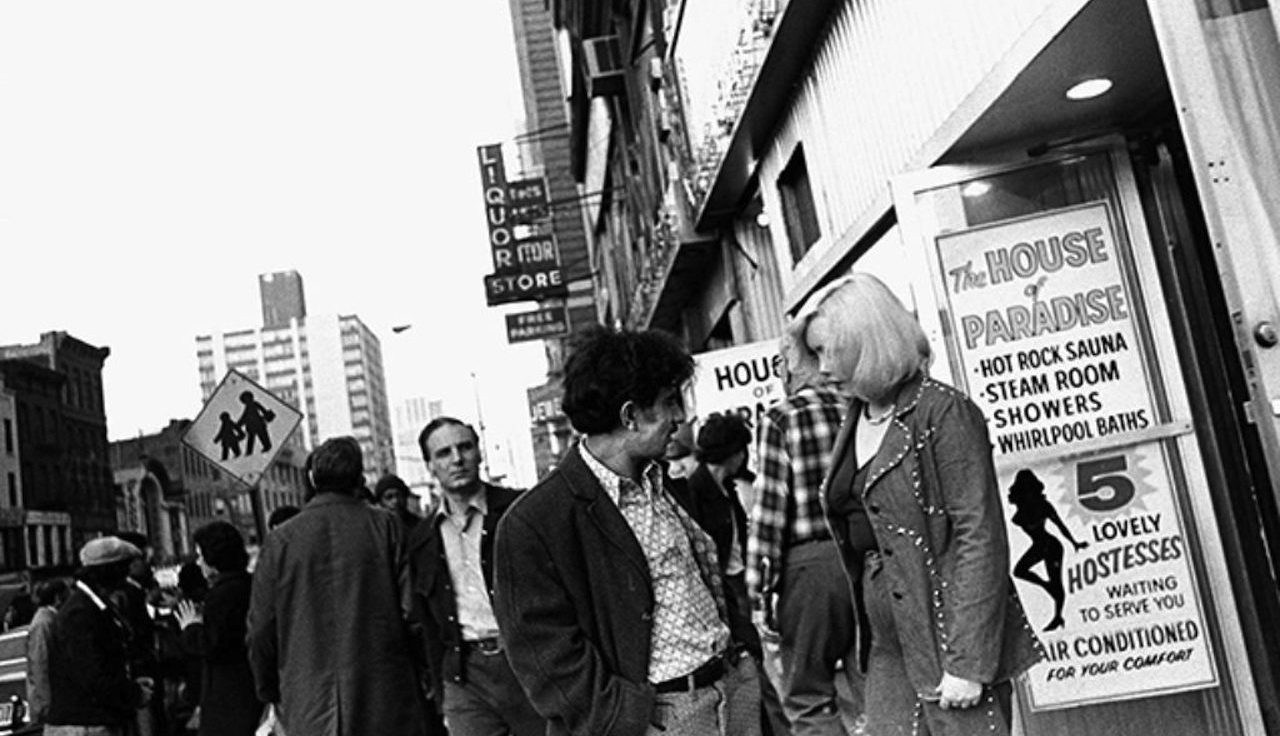

With an eye-catching cover illustrated with the gritty image by street photographer, Leland Bobbé, Blue Money is itself a gritty portrait of a time when sex and drugs were cheap thrills easily found at the crossroads of Times Square.

In this excerpt, Capron writes about Michael, her favorite drug dealer and his love of crystal meth.

After Corinne’s, I cut over to the Traveling Medicine Show, a saloon on Second Avenue and my old hangout. I had been avoiding it for a year —that is, until a week ago.

In the late sixties, we had a real St. Vitus dance going there, a whirling dervish of sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll. Not only did I believe in magic then, I sought evidence, praying for signs, such as the supernatural handwriting that leisurely spelled God’s message to me, carving words in the sawdust across the barroom floor. Miracles of this kind only happened when I was whacked on methamphetamine, which was also when the divine order of things revealed itself, when inanimate objects gathered together to portend, when colors became backlit with the unseen rays of the moon, and jukebox tunes reverberated against the otherwise undetected, hollow sound of nothing. Crystal meth charged the circuits of my brain, leaping over synapses, chasing L-dopa down sleepy channels as sluggish as damned rivers until the banks of my mind flooded with revelation.

I did not fear this state, the drug-induced madness rightfully called “amphetamine psychosis”; I pursued it, guided by my own benign, urbane Charlie Manson, Michael McClaren.

Michael believed in crystal methedrine. Speed is to cocaine what heroin is to morphine—a very strong, very hard drug. But we cherished the tattered government brochure always circulating somewhere in the bar classifying methamphetamine as a psychedelic. This confirmed for us that it was a sacrament. After a few sleepless nights, I would grow preternaturally calm, and the high began to seem indefinite the way love does when it’s good. Michael administered lines of this powerful substance like a kind and watchful small-town doctor who runs a makeshift clinic full of locals come in for the cure. He believed and infected us with the belief that crystal methedrine could heal. We were all convinced. About this we were not cynics in the slightest degree.

Michael had invaded like a missionary from Greenwich Village in the spring of 1967, transforming a dreary Upper East Side singles parlor into what was for me a palace of the night. The corner saloon was lit by an eerie copper glow; the place oozed with drugs, and the small stage rang out with free music played by friends of Michael’s who dropped by to try out new material. The barroom walls were festooned with photographs of these local and world-famous regulars. There were mostly black-and-white head shots of the men, musicians, along with bartenders and drug dealers, all caught in deep and inscrutable contemplation, while the women were displayed in garish color: go-go dancers spinning their tassels on tabletops, or young uptown girls, myself included, wearing tiny bikinis and sunglasses, sprawled over the hoods of shiny cars.

Nothing checked, no restraint, unless it was Michael’s intriguing silences, especially intriguing because probably not a soul uptown or down consumed more speed than he did. And speed made most of us talk and talk in a shorthand of free association, broken sentences tumbling back and forth like flaming torches. But Michael stood out against the pack; he expressed himself in elaborate pantomime instead. He was always tacking something on the bulletin board with his staple gun, or spray-painting a lightbulb crimson red, or brushing his lips with the harmonica he never played, or tinkering with a mike onstage, or just running loose, a marvelous rhythm to his jerky step, the speed spinning him from wall to wall. All of us, his unabashed followers, loved to watch him. His long black hair streamed behind him. His skin was as white as candle wax, except for his flushed cheeks. His wide-set eyes were transparent ice blue, fixed with the vacant stare I once saw in a timber wolf’s eyes. You could almost hear his mind, as high as a whistle pitched for wildlife, and his mind drew us there night after night, all the young girls you could imagine, and the boys, too: we were enchanted.