DANTE FRESSE’S HIM/HER

Artists Seek Refuge From Love/Life at the Met

New York,

Artists find refuge in such a solemn place.

In corners, I hide,

A couple talks in a nearby coffee shop,

I watch them speak–

And she spills the coffee,

Wiping tears from her face;

He spills the sugar reaching for napkins;

They both feel alone,

But in their grief

Find a resolve

To leave the coffee shop with poise,

Hand-in-hand.

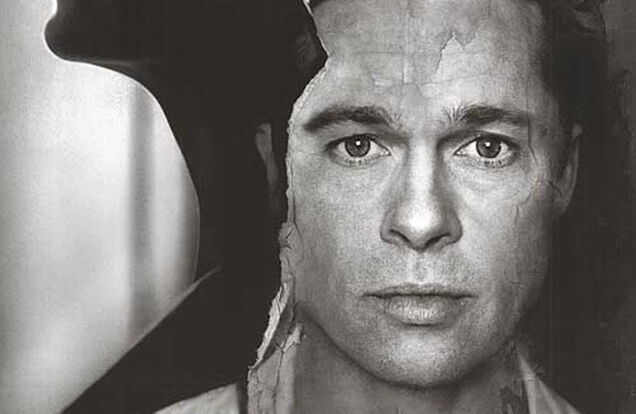

Him/Her

Him

I looked in those eyes again, and her spark was gone. She pulled her gaze away from me and gently pushed back a hanging strain of hair. She was not crying; instead, she was distant. I felt her drifting away and had no words to pull her back.

“Jules, I love you,” I said. The sound of these words widened the glacier between us. She moved a half-step back, and I resisted stepping closer to her.

“Nathan, I think we need to spend some time apart,” she said.

Her words triggered a memory. We had visited the Metropolitan Gallery for an exhibition of paintings by Johan Christian Dahl and Casper David Friedrich that morning. In their works, large and menacing landscapes contrasted with tiny human figures.

The exhibition had over 100 paintings curated across eight rooms. I moved through each as quickly as possible. Julianne lingered, strolling through space and meditating on the art. I became impatient.

“Julianne, come on—they’re closing soon.”

My body turned to face the exit of the museum. Julianne stood still and waved me off from afar. I turned back to look at her. Her eyes were focused on a large blue painting. Her body was still, and she looked deeply into the work.

I walked up to her and grabbed her arm lightly, “Listen, we’ve been here for a while, and I’ll tell you that there’s nothing in here worth staring at any longer.” Her gaze met mine. Her eyes were sad, looking at me as if she was a little girl again.

She looked at me, wanting to say something, but, instead, stayed quiet. Finally, I looked at her frustratedly; I wanted to leave the museum. But, while waiting for her, an email from HarperCollins flashed from my memory:

“Dr. Casen, our publishers expect the first draft of your book by this Friday. Unfortunately, we are unable to grant another pushback on your deadline. The contract you signed demands that your work is submitted according to schedule.

All the Best,

HC Publishing

“Let’s go. I need to get back to my book,” I said.

“In a minute, Nathan,” she said. Then, she dipped calmly back into her mediation on the artwork. Her reaction infuriated me. I was anxious about my deadline. So, my eyes did not leave Julianne. She no longer acknowledged my stare, remaining fixed in her analysis of the painting.

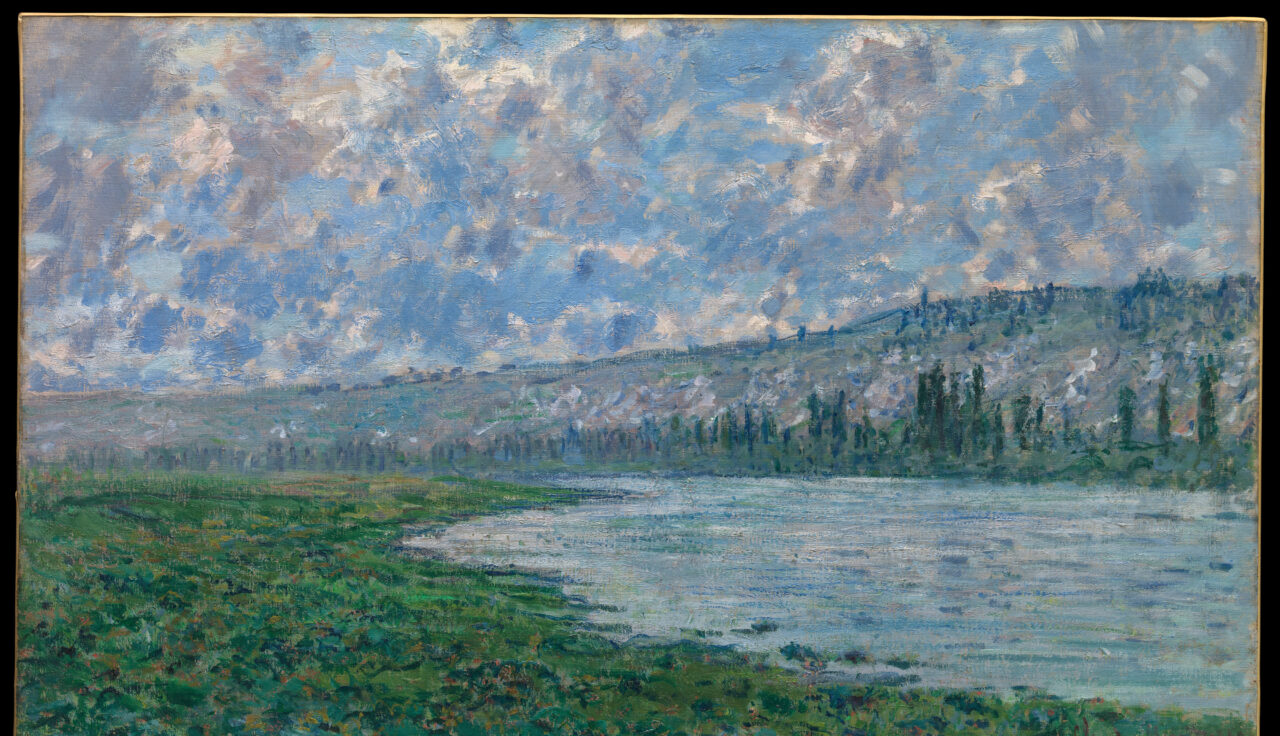

“Miss, I seem to notice you take a liking to the Monet,” a tall, middle-aged curator in an expensive-looking suit came over and said. She looked up and connected her eyes with his.

“Yes, it’s beautiful. I’ve always loved Monet; the way depth unfolds in his paintings.”

“Your eyes are trained for this, I take it,” he replied.

Julianne pointed her head towards his, “I’m an artist myself.”

“What do you paint?” he answered.

“I like painting nature.”

“We don’t get too many natural landscapes in the city,” he replied.

“I find my way,” she said.

“Okay,” he said. This man smiled, turning his body towards Julianne. I eyed her posture as she responded, keeping my distance but evaluating the situation to judge whether I would need to remind them of my presence.

“I’m this fine young artist’s husband, Nathan,” I interrupted.

“Oh,” the man responded, “and Nathan, are you an artist as well?”

“I teach English at Princeton, my alma-mater.”

“I always appreciate an Ivy education. I majored in Art and Art History,” he looked over at Julianne.

“I went to Brown, too, Class of ’73,” she said.

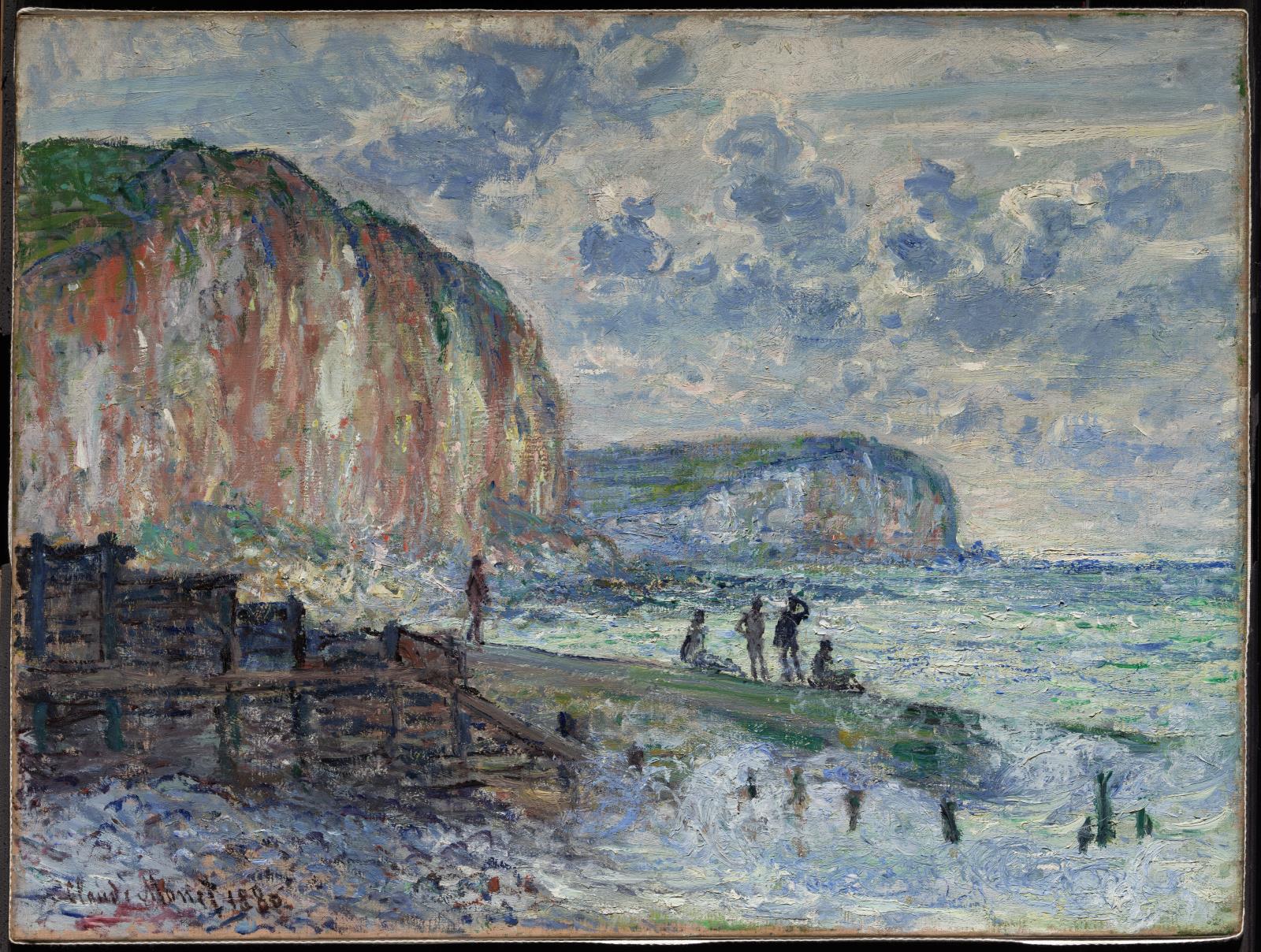

“Interesting, I was ’71. Hard to imagine I passed you over—” the man paused, then turned back to the Monet in front of us. “Anyway, Julianne, your appreciation for this beautiful Monet is rightly placed—it pulls from Naturalism of the Romantic Period, where artists like Kensett and Sands left off with their depictions of the sea.”

“Monet himself painted this same cliffside in France hundreds of times, rendering images of it from multiple angles to capture the shifting “moods of the ocean…”

I walked away from them and observed the rest of the art. Manet, Renoir, and the romantics were hanging on the walls adjacent to me.

Resting, I sat on a red-velvet bench in the center of the room. I thought of how much work I still had to get done once we got home and then how the publishers would cancel my contract if I couldn’t finish this draft of this book. I felt Julianne now prevented me from getting all this done. I looked over at her again, conversing with the slick-haired curator. His hands excitedly moved as he spoke. His tie was bright, and he wore a potent cologne that smelled like peppermint.

“Nathan’s a writer. He’s working on a book now, actually,” Julianne said, smiling over at me. The curator quickly nodded in my direction before returning to their discussion.

My eyes caught a painting, The Monk by the Sea by Casper David Friedrich. A lone monk starred up into the Heavens, hidden behind a thick wall of clouds. A vast black ocean surrounded him. The dark sea juxtaposed the monk’s miniature stature, capturing his insignificance in the boundless face of nature. Overhead, the light seemed to indicate the omniscience of God. Friedrich intended this symbol of God’s ubiquity to give the viewer a feeling of hope. In other words, even when alone, in darkness, the Heavens watch down on us from above. I saw something very existential about Friedrich’s work. However, as I looked deeper, I saw fear in the monk, imposed by the threatening waters, which seemed to hover like predators over prey.

The sea appeared massive. From my view, the clouds block the monk from his vision of God and enclose him in the coal-black sea. There was a false promise of a savior from behind those clouds. In a void, he finds himself alone against nature and victim to its chaos. As he does, we all stare into the abyss, praying to receive mercy from some divinity. I saw myself morph into the painting. I reasoned that we pass through these waters alone only to die, anticipating whatever judgments may come. I felt the blackened water spray against my face, and harsh winds blow through my clothes, attacking my skin. I looked up to see only clouds in sight. My eyes burned from the saltwater. I felt the wet sand harden beneath my feet. I needed the light from behind the darkness. I needed light.

“Enough!” I yelled, getting up from the velvet seats. Julianne and the curator cut their conversation off and froze, turning slowly to look at me. I shook my head and responded to their surprised stares with fury, “It’s a little rude that you two have chatted away for 20 minutes while I’ve been sitting on this bench alone!” I directed my rage at the curator, but Julianne remained in my periphery. “You guys have finished the Monet discussion by this point. Now there’s no need to mess around and talk about your mutual friends or any other topics that seem so important as to keep me waiting here for half an hour.” The volume of my voice escalated as I went on.

“Leave us now and go about your business.”

At this moment, I felt a timid hand touch my left shoulder and turned to face it.

“Sir, the Met closes in five minutes. Everyone but the staff needs to exit the building,” a man in a suit replied from behind me. I brought myself back to reality. The curator escorted us out and gave Julianne a kind-hearted wave.

“Keep working on your art, I’d love to see something in person,” he said before leaving.

Julianne and I walked to the apartment and sat quietly for a while before I looked up at her face. There was what felt like immeasurable darkness surrounding me. I felt alone. She looked up again at me as I imagined a cool, seaborne breeze brush against my face.

“Nathan, I think we need to spend some time apart,” she said.

Her

I looked into his eyes, and that spark was gone. In those disoriented pupils, all I could see was absence and fear. He looked tired, and his hair was frayed. His hopeless leer was desperate. His angry eyes wanted me to accept this shell of the man I once knew.

I felt him drift away. I looked up and saw a mask, hiding immense pain behind a fake smile and anxious words. You could hear it in the way he repeated his words and gestures. I felt alone in his presence.

“Julianne, listen, I love you,” he said with his eyes on me. I pulled myself back from him. The hollowness with which he spoke contrasted the emotional depth of his meaning.

I replayed a memory from an afternoon where we had visited the Metropolitan Gallery to see an exhibition of 19th-century artists: Monet, Manet, Renoir, Friedrich, and Turner. One of the Turner works, Fishermen at Sea, uses the sun as a perspective, drawing the viewer’s eye where calmer waters lie. Two fishermen must make it through a large storm to reach this clearing. Nathan and I lived like this—looking to surpass one more hump before reaching calmer waters. Yet, we felt we could always overcome it together.

I painted a scene of us at sunset, sitting along the banks of Il Lago di Como in Lombardy, Italy. I depicted the sun dipping beneath the crystalline water. The lake was blue and bright, and the gentle waves crashed serenely. The scene promised hope for our future and infinite possibilities.

We entered a room of Impressionist paintings; my eyes connected to a blue-green Monet. I meditated on it and returned to memories of Il Lago—the water and waves. It seemed so beautiful, carrying infinite possibilities.

“Julianne, come on, let’s get out of here, they’re closing soon.”

I heard him call but stayed in my place and gently waved back. The blue-green mixtures swirled together so carefully. I stared into the waves, remembering Il Lago and who we were. Instead, I felt a tug on my arm and heard a voice from behind me say, “Listen Julianne, we’ve been here for hours— I’m well enough acquainted with pre-modern art to tell you that there’s nothing in here worth…” The voice faded in the distance.

I looked back at him and saw the face of a stranger, nothing like the one from my memories. Instead, I saw eyes that possessed no disposition for charity, wanting only to take from a creature who had almost nothing left to give. Nathan’s nose twitched with frustration while his jaw ground against the tops of his teeth. He looked ready to explode. Yet, on the surface, he held his composure together with a condescending expression that projected all his anxiety back onto me, attacking my confidence and soothing him once more.

“Julianne let’s go, honey, I need to get back to my book. I showed you that message from Harper this morning, we don’t have time to pander to the egos of these curators any longer.”

That book. Nathan had wasted so much time doing nothing but skim articles and laugh at animations on web pages. I told him so many times to write—jump into it, and passion would carry him through the ideas stuck in his head. Every time he would say, “You just don’t understand the process of writing—I need time to reflect.” Perhaps this was true, but he had only reflected in the room; he never wrote. Contemplation is good, but I’d imagine, and I’m no writer, as he had made clear many times, that at some point, words must go on the page.

I refused to let him take this moment away from me now, too. “In a minute, Nathan,” I replied, returning my focus to the Monet. He breathed deeply, swallowing some pride and calming himself down before shifting his eyes away from me. In the corner of my eye, I saw his face—his features dragged from the weight of some unseen burden. It was the book, and I almost felt pity for him. He had been under a lot of stress. I broke from my nostalgia and returned to comfort him when I heard a voice from behind me say, “Miss, I notice you’ve taken a strong liking to this painting.”

A tall man wearing a pressed navy suit appeared next to me. He spoke kindly and with a softness that made me feel at ease. I looked up at his face and responded, “Yes, it’s beautiful. I’ve always loved Monet; he layers his strokes, such that depth unfolds into his paintings. If you stare at it for a while, it looks like the waves are cascading down from that cliff up there.”

“Your eyes are trained for this, I take it,” he said, grinning.

I entertained his interest and replied, “Yes, I’m an artist myself.” My words ignited a passion in his eyes. He returned my gaze with surprise and joy as if he had rejoined with a friend he had not seen in a long time.

“Oh,” he said, his face lighting up, “what kind of works do you paint?”

“Sometimes watercolors, or pastels and oils—it depends on what I’m trying to paint, where I am… there’s always a million factors to consider before I start. If I had to choose, I would say I love painting nature the most.” At this, his eyes became soft.

“I’m sure locations are a challenge for you, we don’t get too many natural landscapes in the city,” he spoke calmly.

“I try,” I said.

“I’m sure you do,” he replied, opening his face with a huge smile. He was nice. Plus, I relished the opportunity to speak about my painting. But, Nathan, we needed to go home—I only imagined how angry he was, having to wait through this conversation. So, it was better to soothe him and get out of here before…

“Ahem, hello there, I’m this fine young artist’s partner, Nathan.”

The man scowled a bit. Then, he moved his attention from me to Nathan and said, “Oh, and what do you do, Nathan, are you an artist as well?”

An arrogant smile spread across Nathan’s face, “No, I teach at Princeton University—it was my alma mater.” I saw his mood shifting. His eyes were losing all connection to the present moment—his mind was elsewhere. Whenever he wasn’t focused, I noticed that a smile appeared on his face; he wore it in disguise when he was upset. Something was bothering him. I wondered. Could it have been this man? Nathan, intimidated by this stranger? Is that how far we’d come apart, that he thought a simple gesture like that could garner my affection?

“…my alma-mater was Brown…” I wanted to see if he did not trust my loyalty or if the two of them were showing off.

“…I dabbled in the Fine Arts before committing wholly to studying those who could actually do the work that I was attempting,” he finished. I caught the end of his sentence and chimed in, “I went to Brown, too, Class of ’73.”

“Really?” he answered, tossing a flirtatious glance in my direction, “I was ’71. I can’t believe I missed you, hard to imagine I passed over such a–” And then he smiled, and then he stopped to look back at Nathan. I did, too. Nathan’s expression had adopted a more hostile demeanor. I liked that.

The subject changed. “Anyway, back to your appreciation of this beautiful Monet; it pulls from Naturalism of the Romantic Period, picking up where artists like Kensett and Sands left off with their depictions of the sea.” I had learned about all this as an undergraduate in Art History 101, but I feigned interest in what he was saying, nonetheless. However, this was a mistake, as he began to speak louder and more intensely as soon as I faked my attention in his lecture. He continued, “Monet himself painted this same cliff side in France hundreds of times, capturing images of it from multiple angles to express, as he called it, ‘the shifting moods of the sea.'”

I automated my responses to his statements, nodding when I heard an artist’s name mentioned and trying to seem as interested as possible when he spoke about his career as an artist, followed by his current profession as a nationally renowned curator of 19th-century artworks. The conversation became a monologue. After a while, he began to ask me if I had worked on anything recently. I replied no, but tried to change the subject, saying, “Nathan’s a writer, who’s working on a book now, actually.” I had hoped to involve him in the conversation. I turned around to look for him, but he was gone. I panned the room quickly, catching him sitting on a red-velvet bench in the center of the space, holding his head in his hands and staring petulantly at a painting in the exhibition. The curator dismissed the interjection and proceeded to speak about his own experience as a writer, doing reviews for Picasso’s work in Barcelona, Spain, where the museum had asked him to curate a special exhibition on the great artist’s late works. The artist’s Blue Period was nostalgic for him, as it brought back memories of his mother, who had family who served in the Spanish Civil War.

Death and abandonment were commonplace in his history, and he found respite in how Picasso depicted the suffering through color. A melancholy tone poured through the artwork, which lent Picasso to connect with the mood of the war: a zeitgeist born of pain and anguish. I saw him open up as he spoke, breaking into how this related to his current job at the Met. The softness of his tone evoked images of gentle waves. Monet. I tried to keep up with his speech, but it always seemed to remind me of another place—the sunset on his words as if in Il Lago. I felt him in the waves. I caught a glimpse of Nathan, standing disparately and gazing at that painting in the other room.

I was beyond frustrated and had transcended into a mode of release by Nathan’s absence. I looked carefully at the man, speaking, then back at the Monet. I pondered on those crashing waves and returned to images of the waters of Il Lago. I remembered that sunset and the lakeshore, where Nathan said to me, “Julianne, I need you” I believed him. We had dreamed together to the sounds of those waves. Crisp crashes were punctuations to our internal rhythms.

“You’re going to paint,” that boy had said. “I’ll write my novel, and then I’ll write letters to publishers to see it published. Plus, your canvases: I know galleries that would see your artwork in them.” He smiled. There had been a pause. “Let me set you up with them, please, Julianne.” There was confidence in his eyes, which assured me that everything was going to be okay. He was fantastic, and I was excellent, and no force in the world could stop us from succeeding and taking everything from it. But then, the waves had stopped crashing. It had been storm after storm without any clearings. Swimming past deluges, I thought I had seen it beyond the waves, which crashed gently into one another—a clearing, the light. We had made it. Once more, we did. Just once. It was all we had needed. Then, it was him and I, us together in Il Lago. For what felt like eons. I love you, he says, by the shimmering pool with waves of green and blue. He loves me. And I love him. We. Are.

“Enough!” I heard Nathan erupt from behind me. The shout had cut off the curator’s speech, and he stopped speaking. I turned around quickly to see the loud voice was from Nathan, who charged like a bull, swiftly towards the curator and me. “You don’t think it’s a little rude that you two have chatted away for 20 minutes while I’ve been sitting on this bench alone, waiting for you to finish?” His voice raised. “I think that’s enough, okay?!” He began to scream, and there was no hiding his rage now. “You guys have finished the Monet discussion by this point, now there’s no need to talk about your mutual friends in college, or any other topics that may seem so important to you, as to keep me waiting here in the dark for half an hour!” His eyes looked mad, and I felt my heartbreaking. “You need to get away!” he said to the curator. “Leave her to me and go on about your business; do your fucking job before I report you to your supervisor or get your ass tossed out of here on the street!” I felt past and present collide. Il Lago. The waves.

A man poked Nathan on the back softly. “What?!” the word blasted like a shotgun shell from his mouth.

“The museum closes in 5 minutes, sir. Everyone besides the staff needs to exit the building.” The man wore a red maintenance suit. Nathan’s shoulders dropped, and his body tensed. He looked around nervously before stopping at me and gesturing that it was time to go. As I walked past the maintenance man and curator out of the gallery, my eyes connected with artwork by Casper Friedrich, Sea of Fog. It showed an adventurer standing at a mountaintop overlooking a sea, which was coated with fog. I juxtaposed myself with this traveler, gazing over unexplored lands which bore a fog of uncertainty, hidden from me now for so long. In my mind, the waters of Il Lago had frozen over now. It was time, I thought, to pursue new possibilities for a future in this unknown wilderness.’ Alone, it was a scary idea, but one ripe with hope and unforeseeable opportunity.

We arrived back at my apartment and sat in silence. I heard waves crashing gently in the background of the apartment. “Julianne, listen, I love you.” These words rang in my head and held on tightly to memories of our past. In a moment, I absorbed all the pleasures that Nathan and I had enjoyed. The loves, the secrets, and promises–kept and unkept–which bound and transcended us to heights unknown. Back in reality, we were still in the apartment, hoping to pass over these storms again, and reach our most transparent waters. Il Lago di Lentini—our apotheosis and undoing. Nothing would ever be like that again. We were not those people anymore—we could never be them. I looked at him one last time. He looked so tired. I was, too. Perhaps, the fog was all that was in sight.

I opened my mouth to speak. Looking at him, I said, “Nathan, I think we need to spend some time apart.”