SUMMER IN LOUISIANA

A Secret Love Behind the Barn Leads to Fire

In June, I had grown accustomed to wearing tank tops, and playing outside with Polly. Polly was my sister. At 6’0” she surpassed me in most sports and was my superior in many things.

“Listen,” she would say “You got to grow older so you can meet me in the flow of things.” She called me names for being too small to play with the other kids, then forced my face in the cedar chips outside on my front lawn, then bellowed loudly at the other kids, who laughed at the sight of my beatings.

My father and I had tried but never got along. He’d take me for long walks, but ridicule me for being bad at football. I responded each time with a the silence that characterized most of our conversations.

That summer, I grew my hair to shoulder length. My father belittled me for that decision, but I found it fit the state I was in. Mother had been gone for years now, so during the evenings, when dad was home from work he’d remain aloof in the living room, watching television. I stood at a distance from the door connecting my room to the hallway, peering into his space. He was about a foot taller than me and could envelop me whole with his grasp. I ached to know him better, but the distance between us simply grew.

So, in the summer of 1975, I decided to grow out my bangs and grow my hair to shoulder length. In many ways, I wanted to recreate myself into someone who was altogether new and authentic. In the South, many people were struck in tradition. Jim Crow posters dressed our city along with the broken fences of the Civil Rights Era.

There was a stagnation among the people of Louisiana, a fear of the new; I recognized it as a phobia of the truth. That underscored all the things of our norms and brought together a static culture. It suffocated life and created an overwhelming paralysis.

To break from the stillness of town, I played with Jasmine, who read books to me during the hot summer. In the morning, Polly and I worked with my father in the fields. I kept brushing hair out of my eyes; that pissed my dad off. He was imprisoned in Southern life, which was “1. God. 2. Football. and 3. FAMILY.” Our father echoed these tenets throughout our house, as we all came to eat our breakfast. Pa liked hanging out with Sis more. She had been better at football than anyone in the family and she loved going to Church. He kissed her gently on the forehead each Sunday, while we lined up to pile into Pa’s beat up, old Grand Cherokee and drive to St. Mary’s.

As heat waves sapped us of our energy, you felt the way that he had breathed angrily at the sight of my bushy hair, swaying back and forth in the car, with sweat dripping from my forehead. I sweated profusely in my church clothes.

Johnny Mitchells’ boy, Ben, was an all-star athlete, who would brush against my arm and say, “Kid, when are you going to get better with them footballs? You’re letting old Polly here make you out to be a square. The rest of the kids is catching up.” ‘Is catching up,’ was a standard in southern culture; everyone was poised to catch up or be ahead of another. It was a deadly competition that destroyed my time and ended my abilities to relate to others. Ben would brush up against me, and then pat my father gently on the arm, nodding at him as he passed.

In response, I read and dwelled in the platitudes and fantasies of novels, filling a life which I had yet to explore. Philosophical inquiries, predicated on unfulfilled hopes and fallen dreams, combated realities which are altogether grim and uncomforting. I told Polly once, that reading was a new way of exploring self.

My sister did not read often. Instead, Polly had poor grades and picked on the other kids in class. Once, a boy, Roger Burnhammer, asked Polly to a dance one evening at the school ball. She tried to hide her glee, but her joy was made apparent through the way she got ready and spritely took off before the evening’s events. Upon reaching the ball, in her lavish red dress, Polly looked for Roger to walk her in the side door. It was obvious she had imagined a night of beautiful dancing, with a spotlight placed on her for the first time in her life. I saw her in a new light during that period.

She glowed with confidence. But, upon reaching the ball, Roger was absent. When she asked a nearby student where he had been, he replied that Roger drank and did not intend to come to the ball that evening.

Although she did not admit it, that news crushed my sister. She folded when she realized she had been stood up. Roger played sports, dressed well, and liked lots of the girls. None were as un-girl-like as my sister. No matter what, Roger remained popular. The evening of the dance, Polly returned home and was catatonic for days after the incident. She did not confide in dad or me. I had never seen her in such a state. Polly detached from everyone and kept to herself. She barely ate or slept and every morning she would grunt at me.

I slept well during the fall of Roger Burnhammer. The only time I’d ever wept for our family was after Titan died. He was our puppy, a great dane with large ears and a signature stoicism that my Father loved. In the mornings, he’d kill deer with the dog and hunt with him to get pelts home for skinning. Father never wanted anyone taking Titan for hunts except him. If Polly tried, he’d say she wasn’t a boy so she couldn’t be trusted with the dog. I was left out of each discussion because Pa didn’t trust my companionship. Pa loved him so much and Titan was the rock of our family, the center we all clung to.

After Roger, and throughout the beginning of that summer, Titan was the next greatest passing in our family. After both tragedies, Polly picked on me less. She swept by me with a certain malaise that didn’t characterize her former, domineering, powerful personality. I stayed away and waited for her to pass through that phase, but she never did. It was as if a piece of Polly died during that incident, which would not grow back.

I kept up with my studies and played with Jasmine in the gardens during that whole summer. As the days passed into nights we would read and discuss news of the town with one another. There was a lot of commotion over a new African American family, the Loubins, who moved in. It followed school integration,and Black families banded together. Our local history indicated that Blacks lost land to Whites. Many of the residents now petitioned for the redistribution of land to Black families.

“I don’t know how much more yelling I can take from the people next door. The Loubins haven’t stopped arguing with the city councilmen since last month,” Jasmine complained to me, “I hear them on the phones cursing, saying they want land back or something bad’s gonna happen.”

“They’re fighting for what’s theirs,” I responded, “I think.” The autumn leaves blew into big piles for us to sleep in, so we’d talk for hours outside about politics and the way things fell apart in our town. At school, things changed with the introduction of many Black students to classes. I didn’t have a bother ‘bout it, but some White parents took their kids out of school. However, after a few months, everything seemed to return to normal.

At school, a new student arrived. He was Black and named Josiah. Our teacher, Mr. Skellter, was without prejudice and welcomed Josiah in the class. “Come in Josiah, we’re learning algebra.” The rest of the class continued to sleep through the lecture or didn’t see Josiah walk in. But I noticed how he looked around the room; he judged the character of the place he had come to with aware eyes. He also looked intelligent and carried himself with confidence. Skellter showed him to his seat, then went back to the board.

That day, we learned about Christopher Columbus and the natives. I discovered that Columbus called them Indians, instead of Native Americans, because he thought he had landed in India when he got here. Moreover, we still used that name today–callin’ em Indians on account of his mistake.

“Mr. Skellter,” I raised my hand, “why don’t we just change the name.”

“Well we have, Jamie, changed it to Native Americans, so it’s proper.”

“But I still hear people sayin’ Indian.”

“Them folks ain’t caught up with the times. Change isn’t instant. It takes time,” he said.

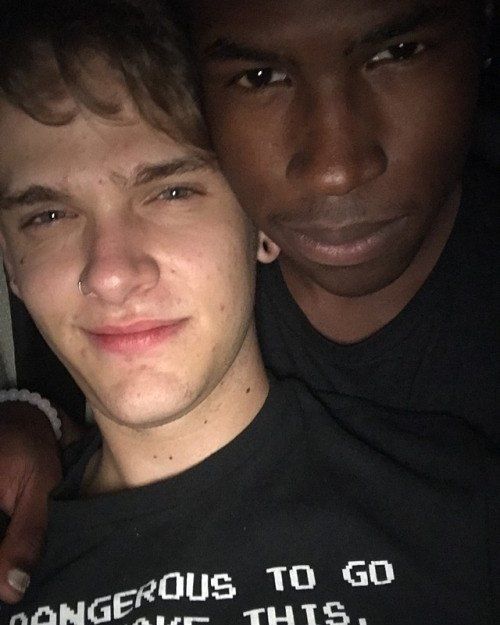

I noticed dimples when he smiled which reminded me of my mother. The room was so hot and my hair had been so bushy that I’d been brushing it to the side about every minute or so. Josiah, sitting next to me, noticed, and pulled out a handkerchief to offer me.

I smiled and took it from him. His handkerchief smelled like mint. I rubbed down my forehead and handed the napkin back to him. He smiled back and put it back. I loved his black skin.

Josiah walked with me after class, taking a turn on the road that led to my house while I kept walkin’. “You live around here?” he asked, pointing upwards towards my house.

“Yeah, just up the road.”

“You mind if I come home with you, I liked what you said about the Indians comment,” His eyes were kind, so I nodded meekly and told him to come up with me to the cabin.

We got to my house and I walked him to the barn behind my house, holding him by the hand to guide us through the trees blocking the path. My palms were sweaty, but I felt sure I was doing the right thing. Polly had gone to the store to buy flour. So, I pulled Josiah over and we sat and talked, for hours, just like me and Jasmine used to. He told me about his family, and how they were looking for reparations, and about the way he’d argue with the neighbors, who didn’t like that he left the African American school. I told him about Pa and sis’. He asked a bunch of questions about what it was like livin’ in Louisiana. I asked him a lot, too, but he didn’t say what I expected. He insisted it wasn’t bad. He said it felt like living with a family of brothers and sisters who don’t get along sometimes but gotta stick together because that’s all they got. I liked thinking about it like that.

We stayed in the barn until night came and he went home. Polly had come back some time ago and strolled silently back inside the house, while Pa hadn’t left from his usual spot on the couch. I stayed for a moment longer, looking up at the moonlight which peeked through the barn windows. Josiah stayed too, the moonlight made his skin shine like lavender. I moved in a little closer, not sure if I was doing the right thing, but locked eyes with Josiah, and he did with me. I moved closer and put my hand on a stack of hay to support my body, as I leaned in. I moved and he did too. I kissed him, and I felt him do the same. We moved back for a second to think about what just went on. He was sure and I was, too. I took his hand and walked him outside of the barn. As I did, I caught Jasmine pulled over the side of the tree outside, with her bike left on the dirt road. I saw her notice Josiah as he left and I let go of his hand to turn to her. He disappeared in the dark woods behind us.

“What you doin’ with the new colored boy from class,” she asked.

“His name’s Josiah. We was just talkin’.”

“Kinda late for just talkin’. You and I usually don’t talk this late.”

“Well,” I replied, shrugging, “me and Josiah did.”

I walked back to my place and Jasmine went off home. She didn’t act the same around me for the next couple days. I wasn’t totally sure why, but the experience with Josiah changed me. I saw him in class and we talked about a lot of things. He’d come over sometimes and sometimes we’d kiss, but he never came inside my house. Daddy was not against Negro people, but I didn’t know how he’d react to Josiah coming inside. It was the anniversary of Titan’s death and he was in mourning. Dad’s buddy, Scooter, would come by sometimes to chat but they mostly talked about guns and sports.

That summer I explored ideas with Josiah and enjoyed sitting with him. Jana would come over sometimes, too, and we’d talk, but it wasn’t the same.

He told me he liked my hair, and I said I loved how his skin shimmered in the moonlight. I was growing around him and felt good about who I was becoming.I asked Pa if I could bring a new friend to our barbeque. He grunted dismissively, indicating a ‘yes.’

For the barbeque, Pa invited Scooter and a few of the other neighbors from town: The Madisons, their family, and James Woodstall and his wife. Jasmine brought her dad, Kalvin, who Pa had gone to school with when they were younger.

Pa set up the grill and a crowd of people stayed around him all day. I waited by the entrance for Josiah.

“What are you waiting for?” Polly asked me.

“Just for my friend to come by.”

Polly shook her head in my direction, joining the rest of the adults, as they asked her questions while I loitered. The Confederate flags on some of the neighbors homes waved proudly in the breeze. I waited for Josiah and kept my eyes on the door.

The councilman and Kalvin had a conversation about the Loubins; everyone listened on account of how important the topic was. Mr. Woodstall took pride in the traditions of the South and wouldn’t deviate from his ancestors and other landowners traditions. Polly tried to participate, but she wasn’t much for political discussion. And Pa didn’t care either, he was just happy to have people around the house. I waited for Josiah. I stood eagerly until I saw him come round from the wooded path outside. I smiled a little when I saw him. I was excited to introduce him to Pa.

Josiah walked up to me and smiled, then we walked inside the party together for everyone to watch. But, as soon as Josiah walked in, all eyes focused on him. The mothers took looked away or stared, while the dads, tried to ignore him. Their eyes unintentionally gravitated to the two of us walking.

“Hey Pa,” I said, walking up to him with Josiah.”

“So, is this your friend?” he said clearly, without his usual grizzled tone.

“Yes, Pa, this is Josiah.”

He looked Josiah up and down then gave him a grin. “Good to meet, you. You eat meat?”

Josiah nodded and dad threw a piece of pork belly on his plate then went back to talking to the others. I nodded, and grabbed a piece of corn and went off, too. Polly didn’t pay us much mind, but kept gazing over in our direction. Mr. Woodstall looked at us constantly. Josiah was the only African American at the barbecue. Or, in town, besides the Loubins. Woodstall came by us and introduced himself to me again, even though I knew who he was. He offered me a drink and I cordially responded, “No.” Josiah calmly waited, not speaking to anybody, but looking at the trees. Woodstall asked me how I knew Josiah; I told him he was a friend from school. Then, he asked if I knew about integration and the strain it was putting on the town and the people in it. I told him, “I don’t feel the difference. Things seem to get back to normal around me.” Mr. Woodstall told me it was more complicated than that and asked where Josiah’s parents were. I told him I didn’t know, I had never met them. Without much more asking, he left me with a pat on the shoulder and he went to talk to Jana’s Pa again. The whole circle looked over suspiciously at Josiah’s presence.

I talked with Josiah all night until everyone was ready to go home. Mr. Woodstall stopped to talk with Josiah at the door. He said a few words to him then nodded sternly and walked out the door. I walked up and asked Josiah what he had said once everyone had exited, but Josiah nodded and refused to tell me.

I walked Josiah out last, and my dad gave him a nod, indicating it was nice to meet him. Polly waved him bye, too. I walked quietly but quickly to rush him out. He told me he only lived a few houses down, pointing over the trees to a clearing. He would be fine walking home alone, he said. I told him good evening and made sure he crossed the wooded path carefully. As I lay in my bed, I looked forward to seeing Josiah the next day at school. The fall semester was coming up and summer classes were almost over. It’d be real school, and the integrated curriculum would bring all the kids together in class. I wondered if it would be easy to see Josiah, like it had been in the summer. “You see the fire?” Polly asked, coming to my room. From my window, I saw a bright orange light, as it burned in the distance. It was coming from Josiah’s house.

I went downstairs to eat breakfast the next morning and Pa was unusually quiet. Polly stayed to her own business. I thought of walking towards Josiah’s, but dad told me he needed me to finish tending our crops before fall sessions started.

That fall, Josiah didn’t come back to school. I didn’t say anything to Pa and he didn’t say nuthin’ either. He took me hunting a few times after to calm me down. He didn’t say nothin about my long hair and football anymore. Polly was quiet, now involved with a new boy at school, Clark. He fished and kept his hair long too, he didn’t stand out much but had a kind way about him. She kept busy but stayed a sister to me when she could. I didn’t see Jasmine much until one day after Halloween when I caught her at the park with her family. She said hi and we talked a little like old times. It was sad, but I was happy to have a friend.

The last night of fall I went in the barn and sat where Josiah and I used to sit and talk in the old days. I remember how his skin used to glow an opal shade when we sat in there. I also remembered how the hay felt in my worn hands as I leaned on it–that night we first came back. I just remembered the way he vanished in the distance as I turned back to walk up my house. I thought now, how I wished that wasn’t the last time I saw him.